|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 15:12:39 GMT

Canis lupus nubilus Great Plains wolf or Buffalo wolf. The plains region from Southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan south to North Texas. This subspecies is extinct. Most were medium sized and light grey, though a black colour phase also existed. canidae.ca/TAXA.HTM# Canis lupus nubilus (Great Plains Wolf, Buffalo Wolf) * Once occurred from southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Canada, to northern Texas. This was a medium sized animal with great variability in color. It was thought to be extinct by 1926, but studies indicate that the wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan are Canis lupus nubilus. (source: IWC) www.lioncrusher.com/animal.asp?animal=35 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 15:17:25 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 15:23:15 GMT

Canis lupus nubilus (Great Plains Wolf, Buffalo Wolf) Last seen around 1926 Canis lupus nubilus The western United States, southeast Alaska and central and northeast Canada. Includes beothucus, crassodon, fuscus, hudsonicus, irremotus, labradorius, ligoni, manningi, mogollonensis, monstrabilis and youngi. canidae.ca/TAXA.HTMThese changes were proposed at the North American Wolf Symposium by taxonomist Ron Nowak. The 24 subspecies listed above were classified using skeletal characters and pelage colours almost exclusively. Now that zoologists have a better understanding of genetics and now that more wolf specimens have been examined, it has been recognized that fewer populations of wolves are truly distinct from each other. Further changes to wolf taxonomy were then made in 1995. There are still only five subspecies of wolves in North America. However, the wolves of Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin are now thought to belong to the subspecies Canis lupus nubilus, not Canis lupus lycaon. Only the wolves of south-eastern Canada would be classified as Canis lupus lycaon. It has been suggested that one population of these wolves be reclassified as Canis lycaon, the Eastern wolf. canidae.ca/TAXA.HTM |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 16:26:06 GMT

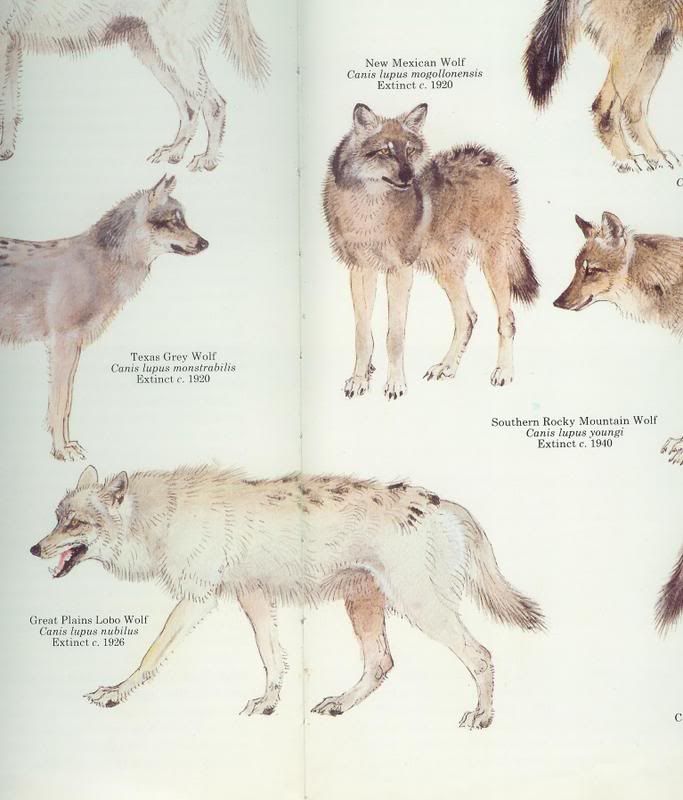

here are more pics from the Doomsday Book of Animals  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 8, 2007 16:31:30 GMT

better moved to rediscovered

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 16:41:47 GMT

The Great Plains Wolf still exists!! Canis lupus nubilus once ranged throughout the Great Plains of the United States and Canada. It is commonly known as the Great Plains wolf or the buffalo wolf. It was thought to be extinct by 1926, but studies indicate that the wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan are Canis lupus nubilus.  So luckely this subspecies of the grey wolf still exists!! ;D |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 16:50:29 GMT

better moved to rediscovered Ok Melanie but it wasn't really rediscovered. As the wolves from this new population that is regarded or suggested as being Canis lupus nubilus were well known and where reclassified as being this subspecies. So shouldn't it be in endangered then? Also as most now invalid subspecies are now classed as Canis lupus nubilus the true Canis lupus nubilus from Southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan south to North Texas is extinct and the new population is known not in this area but from a different location further east some distance away. |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 8, 2007 16:57:40 GMT

The Great Plains Wolf (Canis lupus nubilus), also known as the Buffalo Wolf, is a subspecies of the Gray Wolf, native to North America. This subspecies once ranged across the western United States and southern Canada, but was almost completely wiped out by the 1930s. In 1974, it was listed as an endangered species, and since then its numbers have climbed. By 2004, there was a population estimated at 3,700 wolves living in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Single wolves have been reported in the Dakotas, but these are considered to be dispersers from packs from outside the states and a breeding population most likely doesn't live in either state. A typical Great Plains Wolf is 140 - 200 cm (4 1/2 - 6 1/2 feet) long from snout to tail tip, and weighs between 27 and 50 kg (60 and 110 pounds). It usually features a coat blended with gray, black, buff, or red. The subspecies has grown wary of humans encroaching on its habitat. Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plains_Wolf |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 8, 2007 17:00:50 GMT

Therefor that this subspecies occupy some of its former range in the Great Plains, i think we can say "rediscovered" or "reintroduced". better moved to rediscovered Ok Melanie but it wasn't really rediscovered. As the wolves from this new population that is regarded or suggested as being Canis lupus nubilus were well known and where reclassified as being this subspecies. So shouldn't it be in endangered then? Also as most now invalid subspecies are now classed as Canis lupus nubilus the true Canis lupus nubilus from Southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan south to North Texas is extinct and the new population is known not in this area but from a different location further east some distance away. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 8, 2007 18:35:25 GMT

Ok everyone has there own opinion but i would say endangered simply because this wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan weren't unknown but well known so not rediscovered but reclassified a change in it scientific name and status.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:07:25 GMT

Here is info to confirm what I was saying above Criteria for Recovery in the Western Great Lakes Area This information is posted for historical purposes and does not reflect current state or federal status nor current wolf population counts. The criteria listed below are directly from the 1992 revision of the Recovery Plan For The Eastern Timber Wolf. The original recovery plan was prepared by the Eastern Timber Wolf Recovery Team, an interdisciplinary panel of scientists and administrators assembled by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The team's mission was to come up with reasonable actions to recover and/or protect the eastern timber wolf (Canis lupus lycaon) a subspecies of the gray wolf. At the time the plan was written this subspecies was thought to range from the northeastern United States to western Minnesota. A recent taxonomic review has resulted in the gray wolf population of the western Great Lakes area being newly classified as a different subspecies (Canis lupus nubilus). None-the-less, the recovery plan still stands as the basis for deciding when to remove the western Great Lakes area subpopulation of the gray wolf from the federal list of threatened and endangered species. Recovery Criteria [Before the gray wolf in the western Great Lakes area can be completely taken off the list of threatened and endangered species] at least two viable populations within the 48 United States satisfying the following conditions must exist: 1. the Minnesota population [of gray wolves] must be stable or growing, and its continued survival be assured, and 2. a second population outside of Minnesota and Isle Royale must be re-established, having at least 100 wolves in late winter if located within 100 miles of the Minnesota wolf population, or having at least 200 wolves if located beyond that distance. These population levels must be maintained for five consecutive years before delisting can occur. A Wisconsin-Michigan population of 100 wolves is considered to be a viable second population, because continued immigration of Minnesota wolves will supplement it demographically and genetically for the foreseeable future. Reclassification Criteria The Wisconsin wolf population should be reclassified to threatened status when the late-winter Wisconsin population is maintained at 80 wolves for three consecutive years. Reclassifying Michigan wolves also may be considered at that time. www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/intermed/inter_population/criteria.asp |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:12:34 GMT

Wolf Recolonization in Wisconsin by Adrian P. Wydeven, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Updated September 2000 Although population numbers at the time of settlement in Wisconsin are impossible to determine, a reasonable estimate might be between 3,000 and 5,000 wolves, if density of one wolf per 10-20 square miles occurred. This is indicative of densities found in recent years in the saturated wolf habitat of the Lake Superior Region, including Ontario, Canada. During the 130 years following settlement, wolf populations were eliminated from Wisconsin. Loss of habitat, decimation of ungulate and beaver populations and direct killing of wolves by humans constitute the major factors in the demise of wolves. Wisconsin established a bounty system that lasted from 1865 to 1957. By 1900 wolves remained only in the northern half of the state. By 1950 there were 50 or fewer animals in extreme northeastern and central north Wisconsin. After the elimination of the bounty system in 1957, wolves were granted total protection in Wisconsin -- probably the first protection granted to gray wolves in North America. Unfortunately, the effort came too late to save breeding populations. Wolves were considered extirpated from the state by 1960. From 1960 to 1975, breeding wolves apparently did not inhabit Wisconsin. Only scattered observations of lone wolves and a few pairs were reported during that period. Shortly after the federal protection of the wolf in Minnesota in 1974, wolves began re-establishing themselves in Wisconsin, apparently dispersing from adjacent Minnesota. Therefore, Wisconsin listed the wolf as a state endangered species in 1975, acknowledging its presence in the state once again. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources began formal monitoring of the state wolf population in 1979 through trapping and radio-collaring, winter track surveys and summer howling surveys. From 1979 to 1999, a total of 162 wolves were captured in Wisconsin and adjacent areas in Minnesota. The winter wolf population ranged from 15 to 248 wolves and consisted of 3 to 66 packs. During the winter of 1999-2000 the population was estimated to be 248 to 259 wolves in Wisconsin. Wisconsin's wolf recovery plan was developed between 1985 and 1989. A minimum population goal of 80 wolves was set for the state. The goal was to be achieved through public education, increased legal protection and cooperative ventures to maintain quality wolf habitats. Re-establishment of wolves in Wisconsin depended on the natural movements of wolves into the state and the natural increase in local populations. The population goal was first achieved in the winter 1994-1995 when 83 to 86 wolves were present. The third year of the goal was reached in the winter of 1996-1997. The State reclassified to threatened in 1999, and the federal reclassification process to upgrade wolves as federally threatened started in July 2000. Wolf populations declined in Wisconsin during the first six years of monitoring. After 1985 the wolf populations began to increase at an average rate of 20% per year (see Wisconsin Wolf Population graph). Several factors have contributed to their recent increase. Between 1982 and 1986, researchers found 75% of 32 wolves tested positive for the disease canine parvovirus, but only 35% of 63 wolves tested positive between 1988 and 1995. Despite the persistence of diseases such as canine parvovirus, as well as Lyme Disease, and mange, the wolf population in Wisconsin continues to grow. These diseases apparently affect only small segments of the population. Wolf packs average about 3.8 wolves each, and annual pup survival is at about 30%. The annual survival rate of wolves one year or older was 61% from October 1979 to December 1985. The rate improved to 82% from January 1986 to April 1992. During the early period, 72% of the mortality was due to human causes. Recently it has declined to only about 50% human caused mortality and survival of adult wolves continues to exceed 80% annually. Hunters sometimes mistake wolves for coyotes. So, Wisconsin enacted a closure on coyote hunting during the gun deer-hunting season in northern parts of the state in 1987. In 1996 a radio-collared female was shot during the firearm deer season in northwest Wisconsin; this was the first radio-collared wolf shot during that hunting season in 12 years. People kill fewer wolves now than in previous years in Wisconsin. This is likely the result of better legal protection, a significant increase in public education about wolves and the development of the wolf recovery program. Other factors that may also have helped wolf populations in Wisconsin include an abundance of their main food, the white-tailed deer, and an increase in the wolf population in Minnesota, which provides dispersers to Wisconsin. Wolf depredation on livestock has generally been minor in Wisconsin, with only five verified complaints between 1976 and 1990. As the wolf population continues to rise, complaints have increased. Sixty verified complaints were documented on wolves between 1991 and 19996. These cases involved 37 calves, 1 cow, 10 sheep, 140 turkeys, 46 chickens and 40 dogs (31 killed), and 23 deer (deer farms). Generally, verified losses were reimbursed at 100% of the appraised value, and 9 wolves were captured at depredation sites and transported to other portions of the state. Between 1996 and 1999, the State developed a new wolf management plan. The plan was approved in 1999, and set a state delisting goal of 250 wolves outside of Indian Reservations. In winter 2000, 239 to 249 of the wolves occurred outside of Indian Reservations, therefore the state delisting process may begin in 2001. The wolf plan sets a management goal for the state of 350 wolves. Strategies for managing wolves in the plan include: managing in 4 zones, cooperative habitat management, depredation control and reimbursements, continued legal protection, and intense population monitoring. For additional information, visit Wisconsin wolf management plan. www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/intermed/inter_population/wi.asp |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:13:11 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:14:06 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:14:46 GMT

Methods for estimating the wolf population in Minnesota: Are they reasonable? by Bill Route, International Wolf Center Estimating Wolf Numbers in Small Study Areas Most wolves live in packs and roam an area called a territory. To count wolves in relatively small study areas, say 1,000 square miles, biologists keep at least one wolf radio-collared in each pack over winter. This allows the biologist to fly over the study area to locate the collared wolf and count the members of its pack. Because some wolves disperse (leave or join other packs) and some die, it usually requires collaring two or more wolves in each pack to maintain radio-contact. This takes time and money. Winter is best for counting wolves in the north because there are no leaves on the trees and the background is white with snow. It takes several flights to get a good count of the wolves, usually one or two flights each week, because packs sometimes split up and not all members are observed each time. But eventually, a good count of the number of "pack wolves" in the study area is obtained. The biologist must then add an estimate of the number of lone wolves in the area by calculating the proportion of collared wolves that are not associated with a pack. It takes a lot of time, money, and effort, but the procedures are straightforward and result in very accurate estimates. In fact, estimates for wolves in small areas are among the most accurate of counts when compared to other species, primarily because wolves live in packs and are territorial. Extrapolating Abundance Over Large Areas It is not reasonable to radio-collar wolves in every pack in Minnesota, so biologists have used a three step process. The steps have varied a little over the years, but the 1997-98 survey is a good example of the process. * First, state biologists obtained estimates from all areas where wolves were studied using radio-collars as explained above. Five different studies involving 36 wolf packs provided estimates of average pack size and average territory size. * Second, they needed to estimate the area of the state occupied by wolves. To estimate this "wolf range", 464 natural resource personnel from 179 field stations mapped where they observed wolves, saw wolf tracks or scats, or heard wolves howling during the winter. The observers were also asked to note whether their observations were of packs or single wolves. During the 1997-98 survey, 3451 observations were mapped. Many who worked in the north or northeastern part of the state saw sign of wolves often. Those who lived in the southern or far western part of the state rarely or never saw sign of wolves. All of the mapped sightings were combined with United States Department of Agriculture's wolf depredation data and the telemetry study data to create a single map. This map provided a picture of where wolves were known to exist and where wolf sign was never observed. But, even with hundreds of people in the field, portions of the state were left uncovered. To compensate for the uncovered areas, biologists used a computer to identify the townships that had low human- and road-densities, and therefore probably contained wolves. The human- and road-density threshold they used was based on previous research. The map showing low human and road density merely filled in the holes where observers had not been able to go. Finally, the area covered by major roads, large lakes, towns and cities was subtracted to provide an estimate of the total area believed to be occupied by wolves. * The third and final step, was to calculate the average wolf density found in study areas (from data in step one) and then multiply this number by the estimate of wolf range (step two) for an estimate of the state's total population. The method was slightly more complicated because statistical "confidence intervals" were calculated to provide a range of estimates, but these are the basic steps for arriving at the 1997-98 estimate of 2,450 wolves (range 1,995 to 2,905). Potential Problems One potential for for error is that some observers could have misidentified coyote or dog sign for wolf sign resulting in an overestimate of the wolf range. The authors of the 1988-89 study stated that this was indeed a concern, but believed most of the people who worked on the survey were knowledgeable enough to provide good data. A second potential for error is the use of the human- and road-density model to evaluate areas not traversed by observers. This model identified the Superior National Forest as wolf habitat in 1988-89, and nearly three decades of wolf research proves it is inhabited by wolves. However, observers were unable to traverse the more remote areas, so that without the human- and road-density model, they would have been omitted. In this case, and in many others, it seems reasonable to include the unobserved areas. Comparisons With Estimates Done Elsewhere Wolf populations are estimated each year in Wisconsin and Michigan using similar methods. Wolf range is relatively small in those states, so they can afford to do it annually and can radio-collar a greater proportion of the wolf packs. This results in less reliance on sign surveys and probably greater accuracy. Minnesota's wolf population is roughly five times larger than these two states combined, that level of effort is probably not feasible for Minnesota. Similarly, many packs are radio-monitored in the reintroduced or recolonizing wolf populations in the western United States and can be followed more frequently. Biologists there have already indicated they will resort more and more to sign surveys as their populations grow. In 1997 the International Wolf center evaluated the status of wolves around the world and obtained wolf population estimates from biologists in 34 countries. Of the 28 countries that reported methods, 24 (86%) used sign surveys as a primary method, while three simply used "expert estimates" and one used wolf-harvest data. What Do You Think? When designing a study to estimate the abundance of any species, a biologist must take into account: 1. the resources available (staff time and money); 2. the nature of the beast (some species are more difficult to count than others); 3. the size of the area that needs to be studied (in this case over 30,000 square miles in just the northeastern area of the state); 4. and how critical the estimate is for management of the species (in this case a species being examined for delisting from the federal endangered species list). OK, you are the wildlife manager. Do you think the methods used for estimating wolf numbers in Minnesota are reasonable? www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/intermed/inter_population/wolfest.asp |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 9, 2007 8:15:22 GMT

Wolf Population Expansion in Minnesota William Berg and Todd Fuller Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Populations and federal status updated by IWC December Wolves were bountied in Minnesota from 1849, when they were worth $3, through 1965 (when all bounties ended in Minnesota), when a bountied wolf pelt brought $35. Although bounties generally did not control populations of other predators, they had an impact on wolves. By the early 1900s, wolves were rare in southern and western Minnesota. By the 1950s, wolves were gone from these areas of the state. A wolf study conducted by Milt Stenlund in the early 1950s centered on a portion of the Superior National Forest in northeastern Minnesota. After extrapolation to the rest of northern Minnesota, Stenlund's data indicated a population of 450-700 wolves, most of which resided in 12,000 square miles of main wolf range. Through the early 1960s, wolf numbers were likely stable (see Minnesota Wolf Population Trend graph below). From 1953 to 1965, about 190 wolves were bountied annually, and bounty claims gradually decreased outside the main range -- suggesting that fewer wolves existed. One estimate in 1963 put Minnesota's wolf population at 350-700. After the bounty ended in 1965, wolves could still be legally trapped and hunted year-round in Minnesota. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MN DNR) records indicate that about 250 wolves were killed annually until 1974, when wolves became completely protected under the federal Endangered Species Act of 1973. In the mid-1970s, biologist L. David Mech extrapolated the wolf densities from three study areas in Minnesota to the known wolf range at that time and estimated a population of 1,000-1,200. During the winter of 1978-1979 field personnel from several resource management agencies were queried by the MN DNR. Their knowledge, combined with results from four radio-tracking studies, resulted in a state-wide population estimate of 1,235 wolves. This figure persisted as the official population estimate for ten years. In the early 1980s work by Mech, Steve Fritts and Bill Paul identified areas of newly colonized wolf range that suggested range and population were expanding to the west and south. In winter 1988-1989, the methodology of the MN DNR's 1978-1979 survey was repeated, using an even larger sample of natural resource agencies and personnel, as well as incorporating geographic computer technology. As a check, a second method used the well-established relationship between densities of wolves and ungulates -- in Minnesota's case, deer and moose, to estimate wolf numbers. Both methods estimated the wolf population at between 1,500 and 1,750. There were at least 233 wolf packs, with the average pack size being five. This survey identified about 23,000 square miles of existing and potential wolf range. The DNR wolf survey was repeated in the winter of 1997-98, using an even larger base of natural resource professionals and applying more advanced GIS technology. That survey estimated a population of 2,450 wolves residing in a contiguous pack range of about 34,000 square miles. A total of 385 packs existed in the contiguous range, in addition to several west and south of the "new" wolf range. The successful recolonization of vacant wolf habitat over a span of three decades resulted from high deer densities, wolves dispersing from existing packs, and wolves colonizing new areas. This has been documented in all wolf telemetry studies done in Minnesota. All colonization of new areas has been done by the wolves themselves, unlike some states where wolves have been reintroduced by natural resource agencies. While some wolves dispersed to new areas from the major wolf range identified in 1978, others dispersed from the very few scattered packs in north central Minnesota that survived the bounty era. An example is one pack that the MN DNR had ear-tagged or radio-collared from 1969 to 1980, which occupied a 100-square-mile area southeast of Hill City. Besides being partly responsible for the eventual startup of five neighboring packs, the Hill City pack sent dispersers to Boy River, Walker, Hinckley and Baudette, distances ranging from about 28 to 135 miles. Populations of white-tailed deer, the main prey of wolves in Minnesota, benefited from many mild winters and accelerated timber harvests over the years. These factors, which reduce winter-caused mortality and create more suitable habitat, allowed the deer herd to increase most years, even in the main wolf range. In Minnesota, each wolf takes the equivalent of 18 to 20 adult sized deer per year on average. Based on this average, wolves kill the equivalent of about 40,000 deer per year, compared to deer hunters, who have taken 60,000-80,000 deer across the entire wolf range through the 1995 deer season. But then, winters got much worse. The 1995-96 and 1996-97 winters set records for their severity, and deer numbers decreased by about half. Consequently, deer hunters took about 25,000 deer (all bucks) in 1996 in the Minnesota wolf range, while wolves, whose numbers remained unchanged, continued to take about 40,000 deer. When prey populations fluctuate dramatically, predator numbers usually follow, and wolf numbers stabilized (if not slightly decreased) following the deer decline, albeit temporarily. The winters of 1997-98 through 1999-2000 were among the mildest on record, thereby allowing the deer and the wolf population to again increase. By 1999, the deer hunter harvest had increased to 73,000 deer, and the wolf scent station index (DNR's annual index of the wolf population) rose to a new record for Minnesota. How many more wolves can Minnesota hold? And how should wolves be managed? Wolf populations increased about 6% annually in the 1970s, about 3% annually in the 1980s. All indications are that those increases have continued during the 1990s, and about 4.5% currently. Annual increases of this magnitude can be equated to compounding bank interest in a savings account, and doubling your money (or wolf populations) every 15 to 20 years. Wolf range, as well, continues to increase. Much of the unoccupied and potential range identified in the 1988-1989 survey, and even many areas deemed unsuitable for wolves, now contain wolf singles, pairs or packs. Some wolves are surviving in areas with higher road densities (more than one mile of road per square mile of area) and human densities (more than ten people per square mile) than identified as critical to wolf survival in 1988-1989. Wolf packs have even colonized Camp Ripley in Morrison County. Dispersal continues to areas as distant as the west-central and south-eastern part of the state, the northern Minneapolis/St. Paul outer suburbs, as well as North and South Dakota. Thus, wolves seem to be adapting more to humans and, perhaps due to more education about wolves, humans are becoming more accepting of the wolf's presence. The most wolves that the MN DNR believes Minnesota can sustain without increased wolf-human conflicts is about 2000. The 1992 Eastern Timber Wolf Recovery Plan established a population goal for Minnesota of 1,251 to 1,400 wolves by the year 2000. By the early 1980s, Minnesota had already reached that goal and by the late-1990s had nearly doubled that number. With the recovery of the wolf populations in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service may soon reclassify the wolf in these populations www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/intermed/inter_population/mn.asp

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Nov 12, 2015 11:32:14 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Dec 5, 2015 1:33:00 GMT

"Lost Animals (in Japanese)" by WWF Japan (1996)  |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Nov 28, 2019 6:36:30 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Mar 24, 2021 11:39:58 GMT

|

|