Post by sebbe67 on May 9, 2006 21:22:38 GMT

Is the Malabar civet extinct? Or is it teetering on the verge of extinction? Report by Ajith Kumar, (Down to Earth Feature)

The idea of individual species becoming extinct is quite familiar. It is, however, a poor reflection of our stewardship of the planet. Next to causing its extinction, the greatest crime that we could commit is to declare a speciies extinct, or pretend it is extinct, while it is on the verge of extinction.

The story of the marsupial carnivore, thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), is one such affair. The problem for the species began in 1830 when it was declared a habitual sheep killer by the Australian government and introduced to the bounty-hunting category in 1888. Hundreds of thylacines were killed each year, mostly during the late 1800s.

In 1912, bounty hunting had to be discontinued for want of animals. The last recorded wild thylacine was shot dead in 1930 and it was in 1938 that the species was declared extinct, after the last animal died in captivity.

The Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service was slow in responding. There were more than 300 reported sightings of the animal between 1936 and early 1980s but it was not until 1982 that the NPWSA thought it worthwhile to put money and people on the job of locating the thylacine.

The Australian government spent a large amount of money but no conclusive evidence of the existence of the species could be found. It was concluded to be more extinct than ever before. This is the price the Australians had to pay for ignoring a species when it was on the verge of extinction. If serious action had been taken on the reports and acted upon, thylacines would have been very much around today.

1930-1940 was perhaps the most critical period for the thylacine, when hunting and habitat loss pushed its population to extinction levels. The sad history of thylacine is beautifully summarised by David Quammen in The Song of the Dodo and Eric Guiler, in Thylacine: The Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger (1985).

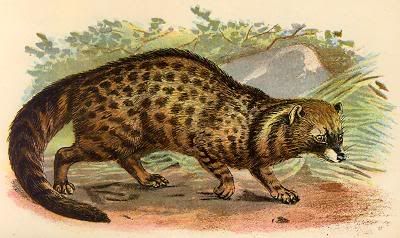

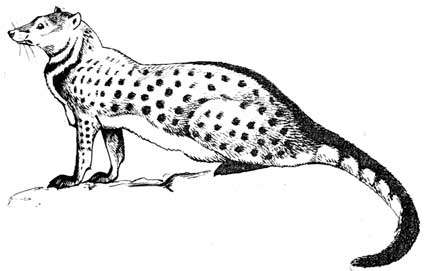

By ignoring history, we often allow it to repeat itself. In India, the Malabar civet (Viverra civettina) is following the same path to extinction. Unlike the thylacine, the Malabar civet never attracted much scientific romance. There are no confirmed sightings of the animal in the wild and no ideas about its tracks and signs. Some early naturalists like T C Jerdon thought it was common along the Malabar coast, while others like A F Hutton said it was common in the hills.

The last known civet ever to be kept in a zoo died in 1929. With no sightings reported for many decades, the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red Data Book (197 listed it as 'possibly extinct'. This proved wrong when G U Kurup of the Zoological Survey of India obtained two skins of recently killed animals in 1987 from the foothills of the western ghats in northern Kerala. Two subsequent surveys in northern Kerala and Dakshin Kannada district in Karnataka, lasting nearly 6 months during 1990 to 1992, produced no live sightings of the animal.

However, two more skins of recently killed animals were obtained from the same place. Carefully collected secondary information revealed that the species was confined to the western foothills, mostly to cashew plantations on private land. These populations are under pressure from loss of habitat and hunting. Following the recovery of skins, IUCN Red Data Book (1996) elevated the status of the species from 'possibly extinct' to 'critically endangered'. The Malabar civet is one of two Indian mammals in this category.

Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act 1991 provides the highest legal protection for the species in India. In March 2000, Matthew Sebastian, wrote about the civet in a Malayalam newspaper and received over 100 responses, mostly from villagers along the foothills claiming to have seen the species on their land or in adjoining forest areas. Some of these reports seem reliable enough.

Today, the Malabar civet is in the same state as was the thylacine during 1930- 1940. What is available are a few 'inconclusive evidences' of its occurrence, compiled by biologists, and several flaky reports of sightings from the public. Recommendations for conservation of the Malabar civet were rejected on the grounds that it was 'hearsay'.

The question we must address is, how can protection laws be enforced to protect the Malabar civet on the verge of extinction? Otherwise, what happened to the thylacine may well be in store for the Malabar civet.

The idea of individual species becoming extinct is quite familiar. It is, however, a poor reflection of our stewardship of the planet. Next to causing its extinction, the greatest crime that we could commit is to declare a speciies extinct, or pretend it is extinct, while it is on the verge of extinction.

The story of the marsupial carnivore, thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), is one such affair. The problem for the species began in 1830 when it was declared a habitual sheep killer by the Australian government and introduced to the bounty-hunting category in 1888. Hundreds of thylacines were killed each year, mostly during the late 1800s.

In 1912, bounty hunting had to be discontinued for want of animals. The last recorded wild thylacine was shot dead in 1930 and it was in 1938 that the species was declared extinct, after the last animal died in captivity.

The Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service was slow in responding. There were more than 300 reported sightings of the animal between 1936 and early 1980s but it was not until 1982 that the NPWSA thought it worthwhile to put money and people on the job of locating the thylacine.

The Australian government spent a large amount of money but no conclusive evidence of the existence of the species could be found. It was concluded to be more extinct than ever before. This is the price the Australians had to pay for ignoring a species when it was on the verge of extinction. If serious action had been taken on the reports and acted upon, thylacines would have been very much around today.

1930-1940 was perhaps the most critical period for the thylacine, when hunting and habitat loss pushed its population to extinction levels. The sad history of thylacine is beautifully summarised by David Quammen in The Song of the Dodo and Eric Guiler, in Thylacine: The Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger (1985).

By ignoring history, we often allow it to repeat itself. In India, the Malabar civet (Viverra civettina) is following the same path to extinction. Unlike the thylacine, the Malabar civet never attracted much scientific romance. There are no confirmed sightings of the animal in the wild and no ideas about its tracks and signs. Some early naturalists like T C Jerdon thought it was common along the Malabar coast, while others like A F Hutton said it was common in the hills.

The last known civet ever to be kept in a zoo died in 1929. With no sightings reported for many decades, the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red Data Book (197 listed it as 'possibly extinct'. This proved wrong when G U Kurup of the Zoological Survey of India obtained two skins of recently killed animals in 1987 from the foothills of the western ghats in northern Kerala. Two subsequent surveys in northern Kerala and Dakshin Kannada district in Karnataka, lasting nearly 6 months during 1990 to 1992, produced no live sightings of the animal.

However, two more skins of recently killed animals were obtained from the same place. Carefully collected secondary information revealed that the species was confined to the western foothills, mostly to cashew plantations on private land. These populations are under pressure from loss of habitat and hunting. Following the recovery of skins, IUCN Red Data Book (1996) elevated the status of the species from 'possibly extinct' to 'critically endangered'. The Malabar civet is one of two Indian mammals in this category.

Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act 1991 provides the highest legal protection for the species in India. In March 2000, Matthew Sebastian, wrote about the civet in a Malayalam newspaper and received over 100 responses, mostly from villagers along the foothills claiming to have seen the species on their land or in adjoining forest areas. Some of these reports seem reliable enough.

Today, the Malabar civet is in the same state as was the thylacine during 1930- 1940. What is available are a few 'inconclusive evidences' of its occurrence, compiled by biologists, and several flaky reports of sightings from the public. Recommendations for conservation of the Malabar civet were rejected on the grounds that it was 'hearsay'.

The question we must address is, how can protection laws be enforced to protect the Malabar civet on the verge of extinction? Otherwise, what happened to the thylacine may well be in store for the Malabar civet.