|

|

Post by Melanie on Dec 26, 2005 13:21:50 GMT

California: 100,000-Year-Old Camel Remains Found October 2002 - Yahoo News A geologist searching for earthquake faults at a construction site found something even more earth-shattering: the 100,000-year-old fossilized remains of a North American camel. The discovery by Robert Lemmer yielded four vertebrae - the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae, the thoracic vertebra and a neck vertebra. On Friday, another neck vertebra was discovered in a 12-foot deep trench dug to search for quake faults in the parking lot of a bowling alley. Fossilized bones were covered in a plaster solution by two paleontological preparers, Howell Thomas and Doug Goodreau, and transported to a laboratory at the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. No more remains were found in the area. "That would indicate it was either the kill of a predator or scavenged by something after it died, and the animal dragged off the other parts leaving the vertebrae behind," Thomas said. "Of course, that's just a guess. There's no way to know for sure. But it's a reasonable explanation." Thomas determined the exact species of the camel by comparing its bones with those of another camel at the museum. Camels originated in North America 15 million years ago, and as they died out on this www.crystalinks.com/camels.html |

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Feb 3, 2006 21:47:27 GMT

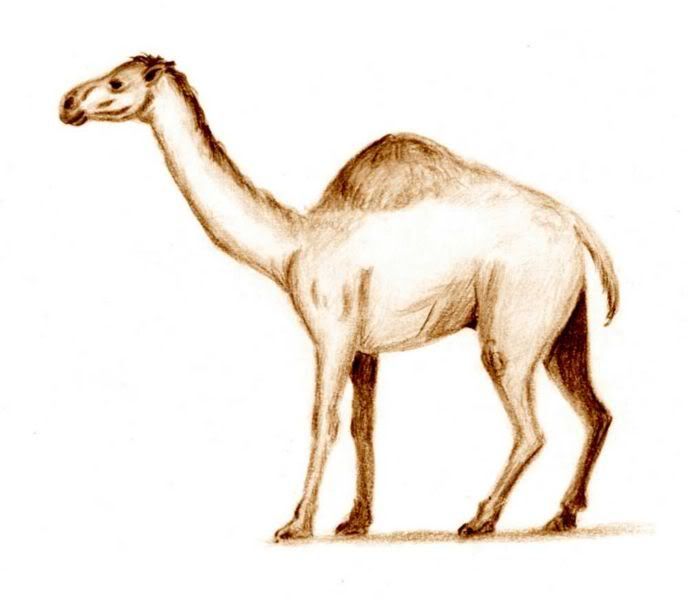

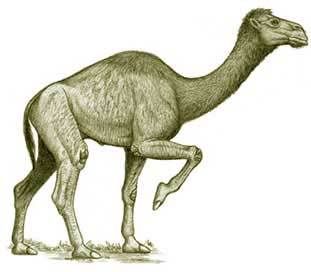

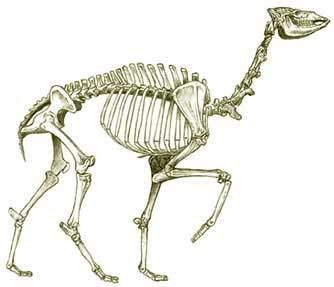

Some pics of the Late Pleistocene North American Camel ( Camelops hesternus) that I have gathered from several sites that I don't remember now: |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Feb 4, 2006 2:01:14 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Feb 4, 2006 12:50:53 GMT

Thank you Melanie. Already corrected. Yes lots of images of a common pleistocene species.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 22, 2008 16:27:13 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 22, 2008 16:33:31 GMT

Extinct Camel Camelops hesternus - This extinct camel was the largest of the two types found at Rancho La Brea. Its head was larger, its limbs were longer and its joints were knobbier than the modern dromedary camel en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camelops |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 26, 2008 0:32:42 GMT

Rare Fossil Unearthed in Southeast Gilbert: Scientists Say Bone Fragment Came From Camel Relative

Posted on: Sunday, 25 May 2008, 15:00 CDT

By Chris Markham, The Tribune, Mesa, Ariz.

May 25--When paleontologist Robert McCord comes to Gilbert, he knows he'll probably dig up something interesting.

As chief curator of natural history at the Arizona Museum of Natural History in Mesa, McCord has been called in at least twice to excavate prehistoric fossils unearthed at Gilbert constructions sites.

"It seems like there should be more," McCord said.

Since the late 1990s, researchers have found four fossilized bone fragments in Gilbert. Two of those finds have been identified as Columbian mammoths -- less hairy, larger relatives of woolly mammoths.

But to scientists, a fossilized bone fragment discovered at the site of a future water treatment facility in southeast Gilbert in March may be the most significant find in the area.

The bone fragment is now believed to come from the left distal humerus -- upper arm bone -- of the ancient Camelops, an extinct species of camels.

"It probably looked a heck of a lot like a modern camel," Mc-Cord said. "A really big modern camel though."

The camel grew to about 7 feet tall at its shoulders and appeared in the late Pliocene epoch, which extended from about 5 million years ago to nearly 2 million years ago. It survived until about 10,000 years ago, during the Earth's last ice age.

For comparison, dinosaurs typically depicted in cartoons and movies became extinct about 65 million years ago.

"People probably saw these (camels)," McCord said.

The bone was found about a mile and a half from where construction crews found "Tuskers," a fossilized mammoth discovered about two years ago that became a virtual town mascot. Town officials held a contest to name the fossilized animal and eventually settled on Tuskers.

The town later named Discovery Park to commemorate Tuskers' nearby final resting place.

"That's why we named it Discovery Park," Councilman Les Presmyk said. "Though that wasn't the exact site the mammoth discovery was made, but it was close enough."

That case was also the first time Gilbert tested its "Mammoth Law," an ordinance passed in 1997 that said construction work must stop in areas where "features of archeological, paleontological or historical interest are encountered or unearthed," to allow for excavation and study.

Without the stipulation, paleontological remains found on private property belong to the property owner, who isn't required to report or donate them for study.

Mort Moosavy, an inspector with Carollo Engineers assigned to the project, didn't know about the law when he noticed the whitish bone fragments that contrasted with the surrounding reddish soil.

But he did exactly what the ordinance calls for by contacting area researchers, who eventually connected him with McCord at the Arizona Museum of Natural History.

Moosavy at first thought the pieces looked like examples of ancient pottery lying toward the bottom of a 15-foot-deep trench -- until he took a closer look.

"Immediately I knew it was a fossilized bone," Moosavy said.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 26, 2008 5:48:10 GMT

Ice Age Yukon and Alaskan Camels It is a poorly known fact that camels (Family Camelidae) originated and underwent most of their evolution in North America. The earliest known Late Eocene (about 40 million years ago) camelids like Protylopus were rabbit-sized with four-toed feet and low-crowned teeth. The sheep-sized Poebrotherium of Oligocene time (37 to 24 million years ago) was common in open woodlands of what now is South Dakota, and had already "lost" the lateral toes. During the Miocene (24 to 5 million years ago), camels increased in size with lengthening necks and limbs, also developing and efficient pacing gait for traversing the expanding steppe and grassland habitat of the time. In the Early Pliocene some 5 million years ago, camels spread, eventually reaching South America and the Old World(via a Bering Isthmus). Some of these camels were gigantic, like Titanotylopus from Nebraska. The South American lineage gave rise to such species as llamas and their relatives all adapted to grazing on high-altitude steppes. Ironically, camels became extinct in their place of origin toward the close of the last glaciation. Although we know a good deal about camels and their origins, few people realize that they once lived in the Yukon and Alaska. Camelid bones recovered in the Old Crow River Basin in northern Yukon are chiefly from large camels, much larger than either the modern twin-humped camel (Camelus bactrianus, which occurs naturally in small numbers in the Gobi Desert of central Asia) or the single-humped dromedary (Camelus dromedarius, used domestically from North Africa to India and now running wild in the Australian outback after introduction there). The fossils are closest in shape and size to a very large member of the true camel group (Camelini) like Titanotylopus mentioned earlier. That camel had long, massive limbs, a relatively small braincase, a convex region between between the eye sockets and well-developed third premolar teeth in both jaws. It was about 3.5 m tall, with long spines on the thoracic vertebrae indicting a large hump. Its snout was shorter than that of Camelops, the other smaller camel reported from Yukon and Alaskan Ice Age deposits. Evidently males were larger and had more robust skulls and canine teeth than females. Titanotylopus occupied western North America from about 5 to 1 million years ago. Could these Yukon Titanotylopus-like camels be relics of an earlier migration to Eurasia, having given rise to Giganotylopus (considered by some experts as identical to Titanotylopus) of the southern Ukraine(Odessa and Cherkassy) about 5 million years ago? A number of bones of another smaller camel (Camelops hesternus, the western camel, distantly related to the modern llamas of South America) have been recovered on the banks of the Sixtymile River near the Yukon-Alaska border. Oddly, all Camelops bones are from the same locality, a placer-mining site of Chuck and Lynn McDougall. In the process of washing away masses of frozen silt("muck") covering the gold-bearing gravels, the miners sometimes encounter bones of Ice Age animals. This particular site has produced hundreds of fossils belonging to woolly mammoth, steppe bison, large and small horses, American mastodon, caribou, mountain sheep, helmeted and tundra muskoxen, caribou, moose, wapiti, wolf, wolverine, scimitar cat, American lion, ground squirrel (with ancient nests and droppings), bird and a virtually perfect carcass of a black-footed feret, fur and all! One of the Camelops bones from Sixtymile was radiocarbon dated to about 23,000 years ago, near the cold peak of the last glaciation. Climate was drier then, and cool steppe-like conditions with broad grassy tracts prevailed compared to the spruce forest that covers the area now, with tundra on the uplands. Thirty-six western camel remains have been reported from mining sites near Fairbanks, Alaska (about two-thirds are from Cripple Creek and Gold Hill; others are from Engineer, Fairbanks and Ester creeks). Dates on a number of the bones range between 40,000 and 25,000 years ago when climate began cooling toward the peak of the last glaciation. So, perhaps western camels did not enter Yukon and Alaska from the south until the relatively warm mid-Wisconsinan interstadial(about 50,000 to 25,000 years ago), dying out there toward the peak of the last glaciation. Western camels were confined to North America, having been most abundant in the western United States, southwestern Canada(Alberta and Saskatchewan) and central Mexico during the last part of the Ice Age(about 600,000 to 10,000 years ago). They probably reached unglaciated Yukon and Alaska by migrating northward via dry terrain on the eastern flanks of the Rocky Mountains during a relativley warm period. How did they survive the northern winters? Modern camels are able to grow thick pelts under cold conditions. I have seen Bactrian camels at ease, wandering over snow-covered land in mid-winter at a game farm in Alberta, and travellers have encountered them "plodding stolidly through north-Asiatic blizzards". In life, the western camel probably looked like a large dromedary, however its limbs were about a fifth longer, its head was longer and narrower and the face was flexed downward to a greater extent. The shape of the snout(premaxilla) indicates that Camelops probably ate as much leaves, forbs(herbs other than grass) and fruits, as grass. The long neck and limbs allow it to reach high browse as well. Camelops seems to have been adapted to arid scrublands and grasslands, and Yukon and Alaskan finds suggest that it could tolerate cool, at times snow-covered steppe-like grasslands. Western camel remains have been reported from at least 18 Paleo-Indian sites dating between about 12,600 and 10,000 years ago(when the species seems to have become extinct). A camel bone chopping tool was found at the Colby site, and there is evidence of butchering at the Casper and Carter/Kerr-McGee sites, also in Wyoming. www.beringia.com/02/02maina10.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 26, 2008 5:52:05 GMT

Extinct Camel Camelops hesternus   The western camel had a very similar build to the living bactrian (two-humped) camel, but was slightly taller (standing seven feet at the shoulder) and may have lacked humps. Although its teeth suggest a diet of grasses, plant remains extracted from its teeth show very little grass and would suggest that the camel was an opportunistic herbivore (eating any plants that were around) like its modern day relatives. The western camel was more closely related to the llama than to living camels.  The basic structure of a camel's foot www.tarpits.org/education/guide/flora/camel.html |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Mar 26, 2016 7:23:43 GMT

Thread title should be renamed as the specific name is hesternus, not histernus. Jass, Christopher N. and Allan, Timothy E. (2016). Camel fossils from gravel pits near Edmonton and Vauxhall, and a review of the Quaternary camelid record of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. doi: 10.1139/cjes-2016-0013 [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Nov 15, 2016 13:13:44 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Nov 19, 2016 13:00:43 GMT

Jones,Davis Brent and Desantis, Larisa R. G. (In Press, 2016). Dietary ecology of ungulates from the La Brea tar pits in southern California: A multi-proxy approach. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.11.019 [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Jan 7, 2017 6:43:47 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Jul 30, 2017 7:01:27 GMT

Zazula, Grant D., MacPhee, R. D. E., Southon, John, Nalawade-Chavan, Shweta, Reyes, Alberto V., Hewitson, Susan and Hall, Elizabeth. (2017). A case of early Wisconsinan “over-chill”: New radiocarbon evidence for early extirpation of western camel ( Camelops hesternus) in eastern Beringia. Quaternary Science Reviews 171: 48-57. [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Jul 30, 2017 8:20:01 GMT

Scott, Eric, Springer, Kathleen B. and Sagebiel, James C. (2017). The Tule Springs local fauna: Rancholabrean vertebrates from the Las Vegas Formation, Nevada. Quaternary International 443(A): 105-121. [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Apr 20, 2018 13:12:18 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Dec 4, 2018 3:18:23 GMT

Buckley, M. et. al. (In Press, 2018). Collagen sequence analysis of fossil camels, Camelops and c.f. Paracamelus, from the Arctic and sub-Arctic of Plio-Pleistocene North America. Journal of Proteomics. doi: doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2018.11.014 [ Abstract] |

|