|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:55:07 GMT

Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island.Guthrie RD. Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA. Island colonization and subsequent dwarfing of Pleistocene proboscideans is one of the more dramatic evolutionary and ecological occurrences, especially in situations where island populations survived end-Pleistocene extinctions whereas those on the nearby mainland did not. For example, Holocene mammoths have been dated from Wrangel Island in northern Russia. In most of these cases, few details are available about the dynamics of how island colonization and extinction occurred. As part of a large radiocarbon dating project of Alaskan mammoth fossils, I addressed this question by including mammoth specimens from Bering Sea islands known to have formed during the end-Pleistocene sea transgression. One date of 7,908 +/- 100 yr bp (radiocarbon years before present) established the presence of Holocene mammoths on St Paul Island, a first Holocene island record for the Americas. Four lines of evidence--265 accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) radiocarbon dates from Alaskan mainland mammoths, 13 new dates from Alaskan island mammoths, recent reconstructions of bathymetric plots and sea transgression rates from the Bering Sea--made it possible to reconstruct how mammoths became stranded in the Pribilofs and why this apparently did not happen on other Alaskan Bering Sea islands. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15201907&dopt=Citation |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:55:33 GMT

Woolly mammoths survived longer on Alaska islandSubmitted by Marie Gilbert Phone: (907) 474-7412 06/16/04 St. Paul, one of the five islands in the Bering Sea Pribilofs, was home to mammoths which survived the extinctions that wiped out mainland and other Bering Sea island mammoth populations. In an article in the June 17, 2004 edition of the journal Nature, R. Dale Guthrie, professor emeritus at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, says that when mammoths on the mainland of Alaska and other Bering Sea islands died out during the extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene era (about 11,000 years ago) those on the Pribilofs survived, and new radiocarbon dates show how. It was a matter of being in the right place at the right time. The mammoth tooth fossil that demonstrates Guthrie's point is the first record in the Americas of a mammoth population surviving the Pleistocene. "During the last glacial maximum, when the sea level was about 120 meters below its current level, what are now the Pribilofs were simply uplands connected to the mainland by a large, flat plain," Guthrie said. Using accelerator mass spectrometer radiocarbon dating, bathymetric (water depth) plots and sea transgression rates from the Bering Sea, Guthrie found that the mammoths became stranded on the Pribilofs about 13,000 years ago during the Holocene sea level rise after the last glacial maximum. "Woolly mammoths became extinct on the mainland about 11,500 radiocarbon years ago," Guthrie said. At that time St. Lawrence Island was part of the Alaska mainland and presumably subject to the same extinction pressures as the mainland, but St. Paul had been an island for about 1,500 years. "Radiocarbon-dated samples from St. Lawrence Island show similar dates of extinction to the mainland," Guthrie said, "but a sample from St. Paul dates to only 7,908 radiocarbon years old, into the mid-Holocene, which is much later." The mammoths were able to survive on St. Paul so long as the island provided enough grazing forage and there were sufficient numbers of animals to prevent inbreeding pressures, Guthrie said. At its present size of 36 square miles the island is too small to sustain a permanent mammoth population. St. Paul became that size about 5,000 years ago, so mammoths likely became extinct prior to that time. St. Paul lies about 300 miles west of the Alaska mainland, and 750 air miles west of Anchorage. Contact: R. Dale Guthrie, professor emeritus, Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, (907) 479-6034, . A PDF of Guthrie's Nature article, "Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island" and an image of Dale Guthrie holding a mammoth molar are available by contacting Marie Gilbert, publications and information coordinator, Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, (907) 474-7412, marie.gilbert@uaf.edu. www.uaf.edu/news/a_news/20040616160137.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:56:05 GMT

Radiocarbon Dating Evidence for Mammoths on Wrangel Island, Arctic Ocean, until 2000 BCS. L. VARTANYAN, Kh. A. ARSLANOV, T. V. TERTYCHNAYA and S. B. CHERNOV ConclusionDuring the last glacial maximum (ca. 20 ka ago), environmental conditions on Wrangel Island proved capable of sustaining habitation by mammoths. Our data show that woolly mammoths persisted on Wrangel Island in the mid-Holocene, from 7390-3730 yr ago. 14C dating has shown that mammoths inhabited Wrangel Island for as long as 6000 yr after the estimated extinction of Mammuthus primigenius on the Siberian continent. www.radiocarbon.org/Journal/v37n1/vartanyan.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:56:53 GMT

Holocene dwarf mammoths from Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic S. L. Vartanyan*, V. E. Garutt† & A. V. Sher‡ *Wrangel Island State Reserve, 686870 Ushakovskoye, Magadan Region, Russia †Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, 1 Universitetskaya naberezhnaya, 199034 St Petersburg, Russia ‡Severtsov Institute of Evolutionary Animal Morphology and Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, 33 Leninskiy Prospect, 117071 Moscow, Russia To whom correspondence should be addressed. THE cause of extinction of the woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius (Blumenbach), is still debated. A major environmental change at the Pleistocene−Holocene boundary, hunting by early man, or both together are among the main explanations that have been suggested. But hardly anyone has doubted that mammoths had become extinct everywhere by around 9,500 years before present (BP). We report here new discoveries on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean that force this view to be revised. Along with normal-sized mammoth fossils dating to the end of the Pleistocene, numerous teeth of dwarf mammoth dated 7,000−4,000 yr BP have been found there. The island is thought to have become separated from the mainland by 12,000 yr BP. Survival of a mammoth population may be explained by local topography and climatic features, which permitted relictual preservation of communities of steppe plants. We interpret the dwarfing of the Wrangel mammoths as a result of the insularity effect, combined with a response to the general trend towards unfavourable environment in the Holocene. www.nature.com/nature/journal/v362/n6418/abs/362337a0.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:57:37 GMT

THE WRANGEL DATE GAP AND OTHER EVIDENCE OF WIDESPREAD MEGAFAUNAL COLLAPSE IN NORTHERN ASIA DURING THE EARLY HOLOCENE (L) Ross MacPHEE Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York NY 10024 What is the significance of the large gap, ~12,000 to 7700 BP, in the 14C record of Wrangel Island Mammuthus primigenius? Did elephants actually disappear from the island during this interval? And what happened to the rest of the high Arctic megafauna at this time? Although the use of chronometric records to determine extinction times is often confounded by sampling inadequacies, Signor-Lipps effects, and other problems, in this case 14C date distributions are consistent with the argument that large mammals may have virtually disappeared from northernmost Asia for a time during and immediately after the Pleistocene/ Holocene transition (PHT). These date distributions help not only to constrain extinctions - long linked notionally with the PHT - but also to identify major local population crashes (extirpations) among those megafaunal species that did not become extinct at this time. Among possible sequelae of the megafaunal collapse are the following: 1. In some cases catastrophe was followed by recovery, with abandoned ranges eventually being restocked from populations hypothesized to have persisted elsewhere. 2. Among megafaunal species known to have survived into the Holocene, mammoths made a very limited recovery, repopulating Wrangel Island (?from the mainland) during the period ~7700 to 3700 BP only. Woolly rhinos (Coelodonta antiquitatis; "last" occurrence, ~11,000 BP) and steppe bison (Bison priscus; "last" occurrence, 8800 BP) evidently did not recover at all. 3. Of great interest is the pattern seen in 14C records for muskox (Ovibos moschatus) and horse (Equus cf. caballus). Both disappeared from the high Arctic during or just after the PHT, then reappeared almost simultaneously shortly after 4000 BP. By 2000 BP, muskox were extinct in Eurasia; horses survived. Although aspects of this pattern (PreBoreal disappearance, late Hypsithermal reappearance) correlate well with climate change, the role of factors such as overhunting and emerging infectious diseases ought to be considered as well. Reference MacPhee, R. D. E., Tikhonov, A. N., Mol, D., de Marliave, C., van der Plicht, H., Greenwood, A. D., Flemming, C., and Agenbroad, L., 2002 - Radiocarbon chronologies and extinction dynamics of the late Quaternary mammalian megafauna of the Taimyr Peninsula, Russian Federation - Journal of Archaeological Science 29: 1017-1042 www.yukonmuseums.ca/mammoth/abstrl-mas.htm#38 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 13:58:17 GMT

Wrangel Island During the last ice age, Woolly Mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) lived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. It has been shown that mammoths survived on Wrangel Island until 1700 B.C. which is the most recent survival of any known mammoth population. Wrangel Island is thought to have become separated from the mainland by 12.000 years BP. Survival of a mammoth population may be explained by local topography and climatic features, which permitted relictual preservation of communities of steppe plants. But due to limited food supply, they were much smaller than the typical Woolly Mammoth. Holocene mammoths from Wrangel Island ranged from 180-230 cm shoulder height. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_elephantWrangel Island During the last ice age, woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) lived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. It has been shown that mammoths survived on Wrangel Island until 1700 B.C.E., the most recent survival of any known mammoth population. They also survived on Saint Paul Island in the Bering Sea until 4000 B.C.E. Wrangel Island is thought to have become separated from the mainland by 12,000 years BP. Survival of a mammoth population may be explained by local geographic, topographic and climatic features, which entailed preservation of communities of steppe plants, as well as a degree of isolation sufficient to delay colonization by humans. St. Paul Island shares this characteristic of geographic isolation, implying that human hunting played a role in the disappearance of the woolly mammoth. Wrangel Island mammoths ranged from 180-230 cm in shoulder height and were for a time considered "dwarf mammoths".[9] However this classification has been re-evaluated and since the Second International Mammoth Conference in 1999, these mammoths are no longer considered to be true "dwarf mammoths". en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_elephant |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:00:04 GMT

Source: Radiocarbon Volume 37(1995), Number 1, page 7 ff. MAMMOTH EXTINCTION: TWO CONTINENTS AND WRANGEL ISLAND Paul S. Martin Desert Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 USA and Anthony J. Stuart Norfolk Museums, Norwich NR1 3JU England A harvest of 300 radiocarbon dates on extinct elephants (Proboscidea) from the northern parts of the New and Old Worlds has revealed a striking difference. While catastrophic in North America, elephant extinction was gradual in Eurasia (Stuart 1991), where straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) vanished 50 millennia or more before woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius). The range of the woolly mammoths started shrinking before 20 ka ago (Vartanyan et al. 1995). By 12 ka bp, the beasts were very scarce or absent in western Europe. Until the dating of Wrangel Island tusks and teeth (Vartanyan, Garrutt and Sher 1993), mammoths appeared to make their last stand on the Arctic coast of Siberia ca. 10 ka bp. The Wrangel Island find of dwarf mammoths by Sergy Vartanyan, V. E. Garrut and Andrei Sher (1993) stretched the extinction chronology of mammoths another 6 ka, into the time of the pharaohs. Not since the early years of 14C dating, when laboratory protocols for sample selection and pretreatment were not standardized or well understood by consumers of dates (see, e.g., Martin 1958 and Hester 1960), has anyone seriously advanced the thought that mammoths or mastodons survived into the mid-Holocene. Those North American Holocene dates of yore were not replicated and could not be supported stratigraphically and geochemically. They moulder in the graveyard of unverified measurements. The 20 new dates on teeth and tusk from Wrangel Island range from 6148 to 2192 bc (Vartanyan et al. 1995). They are accompanied by standardized test measurements of the St. Petersburg Laboratory as well as independent replications (Long, Sher and Vartanyan 1994). Frozen ground at the latitude of Wrangel (70.5°N) is a very favorable environment for preservation of skeletal collagen, thus ideal for dating. The new data set appears unassailable. What does it mean? For one thing, it appears discordant with the idea that a Younger Dryas (YD) cold snap or climatic upset roughly 11-10 ka bp forced megafaunal extinction (Berger 1991). While the YD falls hard on the heels of extinction of North American mammoths (Mammuthus columbi ), horses, camels, ground sloths, extinct mountain goats, sabertooths and others, as well as Old World giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus) in Ireland, all other Old World extinctions precede or postdate the YD (Fig.1; Stuart 1991). Ironically, the YD climatic signal is strongest in Western Europe. Even before 14C dating, it was the basis for correlating pollen diagrams. On oceanic islands around the globe, most doomed genera of birds, mammals and reptiles would disappear, like the Wrangel dwarf mammoths, long afterward, in the Holocene (Steadman 1995). Admittedly, the fossil record on many of the oceanic islands has yet to be traced into YD or earlier time. Late Glacial or earlier extinction pulses remain a possibility. However, when faunas of such an age are known, there is no extinction pulse at any time within the 14C range, prior to the late Holocene (Steadman 1995). Neither the YD, nor the warm-cold oscillations in Greenland core ices known as Dansgaard-Oeschger events that coincide with ice transport of lithic material into the North Atlantic (Bond and Lotti 1995), nor any other independently established climatic perturbation dated by 14C coincides with the extinction pattern outlined above (Fig.1). Although further tests are needed, the extinctions that do not coincide with the YD are as noteworthy as cases that do (or might) fall within its time range. In western North America, the source of the best 14C dates on megafaunal extinctions in the New World (Stuart 1990), the event coincides with Clovis (Llano culture) origins (Haynes 1991, 1993). The number of sites in which mammoth bones were found with artifacts is small, and no bones of horse, camel and ground sloths (to cite a few examples) have been found in undeniable association with stone or bone tools. If the Paleolithic invaders of the New World forced the extinctions, as some propose, it was remarkably rapid, a "blitzkrieg" (Mosimann and Martin 1975), or a "mammoth undertaking" (Diamond 1992). Obviously, the catastrophic model will not work if all New World generic extinctions were not synchronous. Some believe that they were not (Grayson 1991). Critics, in turn, bear the burden of demonstrating how a climatic pulse could force the disparate extinction sequence between the New and the Old Worlds (Fig.1). Another climatic model for mammoth extinction deserves mention. Beringian paleontologists, Russian, Canadian and Alaskan, have long viewed the coming of the Holocene in the far north, with its string bogs, sphagnum, ericads and other herbivore-resistant plants, and with deep snows in winter, as uninhabitable for mammoths and the extinct steppe fauna of Glacial times (Guthrie 1990 and references therein). In the case of Wrangel Island, even before the discovery of Holocene dwarf mammoths, Russian botanists had reported an unusually rich and palatable assemblage of steppe tundra plants, including 15 species of grasses, 4 of wormwood (Artemisia), 10 legumes, many Rosaceae and very few Ericaceae (Yurtsev 1982). Wrangel sounds like an ideal place to survive the loss of the mammoth steppe. Nevertheless, Guthrie's argument leaves unanswered questions of the suitability of other relict patches of grasses and palatable steppe plants elsewhere in Eurasia and North America. Were there no other Wrangel-size refugia for woolly mammoths? What of vast expanses of steppe with dozens of genera of grasses, legumes and Rosaceae and many species of Artemisia and palatable Chenopodiceae in the high dry plateaus and valleys of eastern Eurasia and western North America? Would not western North America offer suitable continental climates for various species of mammoth? Special-case environmental arguments that serve to explain regional extinctions, such as the Beringian mammoth steppe, may sound plausible, until one attempts to generalize more widely. On one matter all "extinctionists" interested in the fate of mammoths can agree: 14C dating has done more to clarify events than any other analysis. The method offers a unique opportunity to evaluate extinctions in many corners of the earth over the last 50 ka. Bones of the youngest extinct large mammals (including mammoths) in the frozen ground of Arctic and subarctic latitudes may prove to be of any age. It takes a serious effort to wade through dozens of dates, most of which are too old by many thousands of years to approach the last millennium when extinction likely occurred. Russian paleontologists and Russian 14C laboratories have worked hard on this problem. They are to be congratulated. Their work confirms dramatically an extinction chronology of mammoths in the Old World that was much more gradual than the one in the New World (Fig. 1). In the New World and increasingly in the Old, the chronology is in step with the spread of prehistoric humans. www.radiocarbon.org/Subscribers/Fulltext/v37n1_Martin_7.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:00:41 GMT

Hi ! I found Mammuthus dwarfus as the scientific name for the Wrangel Island Mammoth, is this name valid ?  |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:01:13 GMT

Hi ! I found Mammuthus dwarfus as the scientific name for the Wrangel Island Mammoth, is this name valid ?  Well its listed as a species in its own right - Mammuthus dwarfus (Wrangel Island mammoth) in wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elephant |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:00:51 GMT

Well I'm skeptical. I'm not sure if it should considered to be valid. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- From: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_elephant: Wrangel IslandDuring the last ice age, woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) lived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. It has been shown that mammoths survived on Wrangel Island until 1700 B.C.E., the most recent survival of any known mammoth population. Wrangel Island is thought to have become separated from the mainland by 12,000 years BP. Survival of a mammoth population may be explained by local topography and climatic features, which permitted relictual preservation of communities of steppe plants. Wrangel Island mammoths ranged from 180-230 cm in shoulder height and were for a time considered "dwarf mammoths".[4] However this classification has been re-evaluated and since the Second International Mammoth Conference in 1999, these mammoths are no longer considered to be true "dwarf mammoths" (source: www.nmr.nl/deins930.html). I have no access to the source, but I think it might be this (not sure): Deinsea 9 2003: (pp 1-562); 36 contributions on ADVANCES IN MAMMOTH RESEARCH: Proceedings of the Second International Mammoth Conference, Rotterdam, Holland, May 16-20. This Dutch Newsletter of the Rotterdam Nature Museum says that the so-called dwarfs were actually females that didn't grow after being pregnant for the first time. At the conference it was concluded that males were much bigger than the females. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:02:36 GMT

Mammuthus dwarfus another example of a species once valid which seems to be merged with other specie recently

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:03:55 GMT

Mammuthus dwarfus another example of a species once valid which seems to be merged with other species recently

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:03:29 GMT

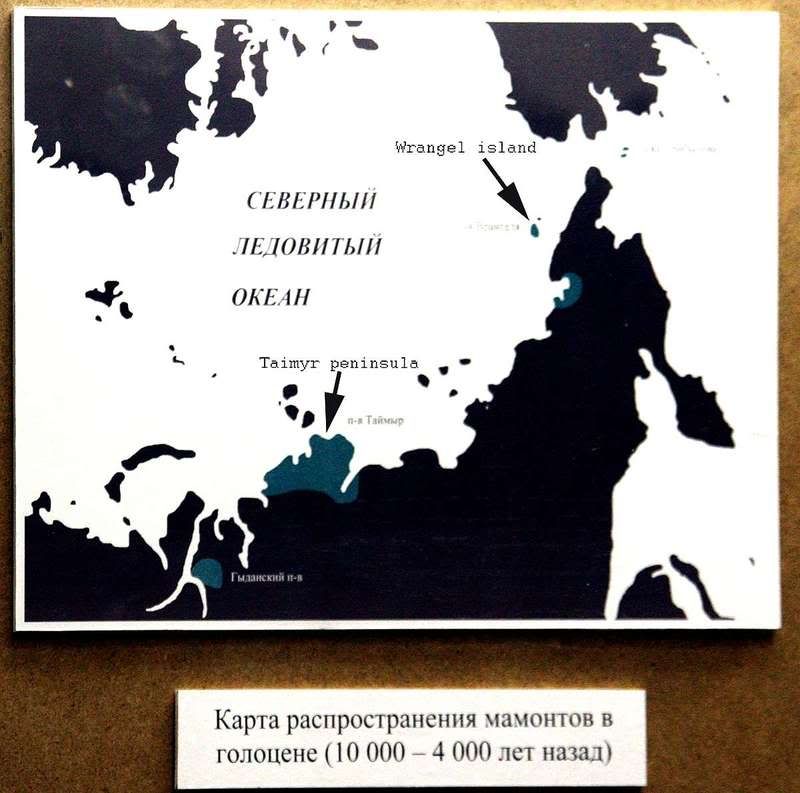

Map of the last known areas inhabited by mammoths on the mainland and Wrangel Island, where they survived until 3 200 years ago. On the boundary of the Pleistocene and Holocene (less than 10 000 years ago) the sea flooded most of the Arctic shelf. The range of mammoths was reduced and were represented in few areas except for small isolated sites in the northeast of Siberia. During the next 4 000 years on Wrangel island, which was separated from the continent 9 000 years ago, a small stable population existed. These Mammoths lived in extremely adverse conditions; animals became small in stature due to lack of food during early development. Among the bones and teeth of the mammoths found on the island, the percentage of remains demonstrating the development of various illnesses is rather high. At the same time, use by adult animals of a wider set of fodder plants and the absence of predators led to the majority living to a ripe old age. The reason for the final disappearance of mammoths on the island is not clear; probably it did not occur without the help of those humans who appeared on the island about 3 200 years ago. Photo: Vladimir Gorodnjanski, 2007, from an exhibit at the ZIN, St Petersburg. donsmaps.com/bcmammoth.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:05:18 GMT

Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island R. Dale Guthrie1 1. Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA Correspondence to: R. Dale Guthrie1 Email: ffrdg@uaf.edu Top of page Abstract Island colonization and subsequent dwarfing of Pleistocene proboscideans is one of the more dramatic evolutionary and ecological occurrences1, 2, 3, especially in situations where island populations survived end-Pleistocene extinctions whereas those on the nearby mainland did not4. For example, Holocene mammoths have been dated from Wrangel Island in northern Russia4. In most of these cases, few details are available about the dynamics of how island colonization and extinction occurred. As part of a large radiocarbon dating project of Alaskan mammoth fossils, I addressed this question by including mammoth specimens from Bering Sea islands known to have formed during the end-Pleistocene sea transgression5. One date of 7,908 plusminus 100 yr bp (radiocarbon years before present) established the presence of Holocene mammoths on St Paul Island, a first Holocene island record for the Americas. Four lines of evidence—265 accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) radiocarbon dates from Alaskan mainland mammoths6, 13 new dates from Alaskan island mammoths, recent reconstructions of bathymetric plots5 and sea transgression rates from the Bering Sea5—made it possible to reconstruct how mammoths became stranded in the Pribilofs and why this apparently did not happen on other Alaskan Bering Sea islands. www.nature.com/nature/journal/v429/n6993/full/nature02612.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:13:45 GMT

Mammoths Stranded On Bering Sea Island Delayed Extinction ScienceDaily (Jun. 18, 2004) — St. Paul, one of the five islands in the Bering Sea Pribilofs, was home to mammoths that survived the extinctions that wiped out mainland and other Bering Sea island mammoth populations. In an article in the June 17, 2004 edition of the journal Nature, R. Dale Guthrie, professor emeritus at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, says that when mammoths on the mainland of Alaska and other Bering Sea islands died out during the extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene era (about 11,000 years ago) those on the Pribilofs survived and new radiocarbon dates show how. It was a matter of being in the right place at the right time and the mammoth tooth fossil that demonstrates Guthrie's point is the first record in the Americas of a mammoth population surviving the Pleistocene. "During the last glacial maximum, when the sea level was about 120 meters below its current level, what are now the Pribilofs were simply uplands connected to the mainland by a large, flat plain," Guthrie said. Using accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) radiocarbon dating, bathymetric (water depth) plots, and sea transgression rates from the Bering Sea, Guthrie found that the mammoths became stranded on the Pribilofs about 13,000 years ago during the Holocene sea level rise after the last glacial maximum. "Woolly mammoths became extinct on the mainland about 11,500 radiocarbon years ago," Guthrie said. At that time St. Lawrence Island was part of the Alaska mainland and presumably subject to the same extinction pressures as the mainland, but St. Paul had been an island for about 1,500 years. "Radiocarbon-dated samples from St. Lawrence Island show similar dates of extinction to the mainland," Guthrie said, "but a sample from St. Paul dates to only 7,908 radiocarbon years old, into the mid-Holocene, which is much later." The mammoths were able to survive on St. Paul so long as the island provided enough grazing forage and there were sufficient numbers of animals to prevent inbreeding pressures, Guthrie said, and at its present size of 36 square miles is too small to sustain a permanent mammoth population. St. Paul became that size about 5,000 years ago, so mammoths likely became extinct prior to that time. St. Paul lies about 300 miles west of the Alaska mainland, and 750 air miles west of Anchorage. Adapted from materials provided by University Of Alaska Fairbanks. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/06/040618070946.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:14:09 GMT

Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island R. Dale Guthrie1 1. Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA Correspondence to: R. Dale Guthrie1 Email: ffrdg@uaf.edu Top of page Abstract Island colonization and subsequent dwarfing of Pleistocene proboscideans is one of the more dramatic evolutionary and ecological occurrences1, 2, 3, especially in situations where island populations survived end-Pleistocene extinctions whereas those on the nearby mainland did not4. For example, Holocene mammoths have been dated from Wrangel Island in northern Russia4. In most of these cases, few details are available about the dynamics of how island colonization and extinction occurred. As part of a large radiocarbon dating project of Alaskan mammoth fossils, I addressed this question by including mammoth specimens from Bering Sea islands known to have formed during the end-Pleistocene sea transgression5. One date of 7,908 plusminus 100 yr bp (radiocarbon years before present) established the presence of Holocene mammoths on St Paul Island, a first Holocene island record for the Americas. Four lines of evidence—265 accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) radiocarbon dates from Alaskan mainland mammoths6, 13 new dates from Alaskan island mammoths, recent reconstructions of bathymetric plots5 and sea transgression rates from the Bering Sea5—made it possible to reconstruct how mammoths became stranded in the Pribilofs and why this apparently did not happen on other Alaskan Bering Sea islands. www.nature.com/nature/journal/v429/n6993/full/nature02612.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:14:44 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:15:39 GMT

This is really fascinating. It would be really interesting to know if the belonged to a different mammoth species than the mammoths of Wrangel. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:16:11 GMT

5,700-YEAR-OLD MAMMOTH REMAINS FROM THE PRIBILOF ISLANDS, ALASKA: LAST OUTPOST OF NORTH AMERICAN MEGAFAUNA CROSSEN, Kristine J., Geology Dept, Univ of Alaska, 3211 Providence Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508, afkjc@uaa.alaska.edu, YESNER, David R., Department of Anthropology, Univ of Alaska Anchorage, 3211 Providence Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508, VELTRE, Douglas W., Anthropology Dept, Univ of Alaska, 3211 Providence Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508, and GRAHAM, Russell W., Department of Geosciences and Earth and Mineral Sciences Museum, Pennsylvania State Univ, University Park, PA 16802 Remains of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) dating to ~5,700 14C yr BP (~6.500 cal yr BP) have been discovered in a lava tube cave on St. Paul Island, an isolated island in the Bering Sea, Alaska. These remains are at least 2,200 years younger than any previously reported mammoths in North America, and are currently the latest dates for extinction Pleistocene megafauna in the Americas. Extended mammoth survival on the Pribilof Islands may have been a function of the complete isolation of the islands from human occupation until the late 18th century, as well as some unique aspects of local geology and vegetation. Like the Wrangel Island mammoths, the Pribilof Island mammoths are at the lower end of the size range for Mammuthus primigenius, but are not truly dwarf mammoths. The survival of the Pribilof Island mammoths has significant implications for both human and environmental theories of Pleistocene megafaunal extinction. gsa.confex.com/gsa/2005AM/finalprogram/abstract_97313.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 2, 2008 14:16:55 GMT

Discovery extends mammoth survival 2,200 years By: Lori Keim Oct 28, 2005 UAA researchers’ discovery has important implications for large mammal extinctions When University of Alaska Anchorage researchers Douglas Veltre, David Yesner and Kristine Crossen, along with Penn State’s Russell Graham began mapping animal remains in a lava tube cave 16 meters (53 feet) below the surface of St. Paul Island, they had no idea that the discovery they were about to make would have very significant implications for both human and environmental theories of Pleistocene megafaunal (large animal) extinction. Detailed in the paper “Last Outpost of North American Mammoths Found on Isolated Alaskan Island”, which Kris Crossen presented this week at the annual Geological Society of America meeting in Salt Lake City, the woolly mammoth remains found in the cave are reliably dated at about 5,700 years BP (before present). The researchers suggest in the paper that their work reinforces the theory that human hunting is the main cause of the widespread extinction of megafaunal species worldwide, which occurred concurrently with the rapid growth and spread of human populations in the aftermath of the Last Glacial Maximum. The continued survival of woolly mammoths on uninhabited Bering Sea islands long after the extinction of their mainland cousins adds weight to the theory, according to Veltre, Crossen, Yesner, and Russell. Qagnax (“Bone” in Aleut) Cave was discovered in 1999 by residents of St. Paul Island, one of five islands comprising the volcanic Pribilof Island group in the eastern Bering Sea. They are the most isolated islands in North America, 500 km (310 miles) off the coast of mainland Alaska, and were uninhabited by humans until the late 18th century when the Russians brought Aleuts there. St. Paul is unique among Bering Sea islands in its lava tube caves, from which animal bones may be collected. Qagnax Cave is a chamber within a lava tube about 15 meters (49 feet) in diameter and 12 meters (39 feet) high connected to the surface by a 4 meter (13 feet) vertical shaft, which made it a perfect natural trap for local animals, including mammoth, polar bear, caribou or reindeer and Arctic fox. The TDX Corporation, the Aleut village corporation of St. Paul, Alaska, gave permission for fieldwork and analysis, as well as in-kind support for a research project. The research project began in 2003 and focused on reconstructing the geologic context, photographing and mapping the cave and the faunal remains, collecting the bones, testing the central debris cone, and dating the mammoth remains. The materials were cleaned and dried and are currently housed at the UAA Anthropology Laboratory. Many of the 1,750 bones recovered evidence carnivore/scavenger alteration, including chewed areas and tooth puncture holes. The researchers concluded that the cave acted as a natural trap into which animals fell, some still alive to consume bones and possibly the carcasses of previously trapped individuals. Tooth dating was done on gelatin derived from the dentine collagen using accelerator mass spectrometry. Two of the teeth and one post cranial bone were subjected to 14C dating. The findings led the researchers to conclude that all of the woolly mammoth bones may have been from a single animal which died about 5,700 years BP. The remains are at least 2,200 years younger than any previously dated mammoth remains from anywhere in North America. The extended survival of isolated woolly mammoths on the Pribilof Islands may be closely related to the absence of human habitation on the islands until the late 18th century. As the climate began to change with the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, polar and glacial ice melt caused the seas to rise, slowly submerging eastern Beringia and creating a maritime environment on the volcanic islands that remained – the Pribilofs – now isolated from the mainland and humans. The islands were free of permafrost and enjoyed relatively slight winter snow cover and longer summer growing seasons. The resulting lush coastal vegetation was very similar to that of the Bering Sea islands of today. The abundance of grasses and other vegetation likely contributed to the species’ surviving more than 5,000 years beyond the extinction of mainland mammoths. The waters continued to rise until at least 5,000 years ago, gradually reducing the grazing range available to the large mammals. Active volcanism until about 3,200 years BP possibly contributed to habitat alteration and/ or fragmentation and may have also contributed to the woolly mammoths’ eventual extinction. Because of their isolation, the authors propose, the Pribilof Islands offer an excellent test case supporting the idea that survival of the mammoths was most likely in areas without human occupation. A University of Alaska Anchorage Faculty Development Grant provided financial support for Professors Crossen, Veltre and Yesner, and the Denver Museum of Science and Nature provided funding support for Graham. www.uaa.alaska.edu/news/mammoth-discovery.cfm |

|