|

|

Post by Melanie on May 28, 2005 19:52:10 GMT

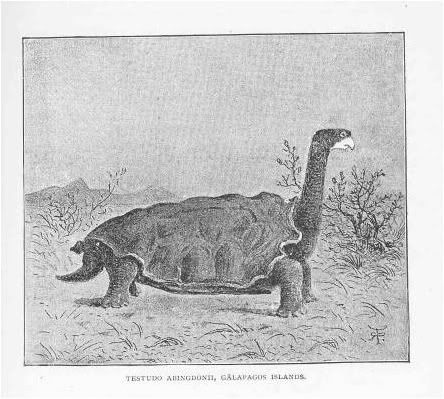

The Abingdon Island Tortoise was thought to be extinct in 1967. But then, in 1971, one male called "Lonesome George" was discovered on Abingdon Island. He was the last surviving member of its kind on an island where the vegetation was almost destroyed by goats, pigs, rats, and dogs. He lives now on the area of the Charles Darwin Foundation. He is perhaps older than 80 years and is still waiting for a mate. The Story of Lonesome George The small island of Pinta is located in the North of the Galapagos archipelago. One of the 11 remaining races of the Galapagos Giant Tortoise (Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni) comes from Pinta, but their history is a tragic one. Whalers and sealers heavily depleted their numbers in the 19th century, some ships taking many tortoises at a time. The tortoises were a good food source as they could live up to a year in the holds of the ships without food and water. Females were generally taken first as they are much smaller than the males and could be found in the more accessible lowland areas during the egg laying season. Before Lonesome George was found, the last reported sighting of tortoises on Pinta was in 1906, when the island was visited by the Californian Academy of Sciences. They collected three males, which were the last tortoises seen on Pinta for the next 60 years. Another issue for the Giant Tortoises of Pinta Island was the presence of goats, which were released by fishermen in the 1950's as an alternative food source. These introduced mammals destroyed much of the vegetation and directly competed with any remaining tortoises for food. The population of goats grew rapidly, devastating the vegetation and causing erosion. In 1971, National Park wardens hunting goats on Pinta came across a single male tortoise. He became known as "Lonesome George". His name derived most certainly from being the only surviving example of his species and "George," after the U.S. actor George Goebel, who called himself "Lonesome George" in a television program. It was decided to bring the animal back to the Charles Darwin Research Station, where there was already a captive breeding program for the giant tortoises. Many years later, "Lonesome George" was placed in a corral with female tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus becki) from Wolf Volcano, located on Isabela Island. The hope was that by placing these animals together, the Pinta race through "Lonesome George" would pass along at least some of his genes into future generations. The Wolf race were the closest morphologically to the Pinta race. The aim was to maintain George's sexual activity for the possibility that a Pinta female was found, or at least back crossing to create as close an offspring as possible to the Pinta characteristics. Unfortunately, he has yet to succeed in breeding successfully with these females, and we do not yet fully understand the reasons. "Mounting" took place, but no eggs resulted. This could be because of the genetic distance between George and the tortoises of Northern Isabela. Scientist Edward Lewis has made DNA scans of tortoises all over the world without finding a match. George's diet is being investigated to ensure there is no deficiency that could be causing his failure to reproduce. We have considered the theoretical possibility of cloning lonesome George, manipulating the gender of the clone, and trying to produce a female. This is theoretically possible, but practically very difficult, and the technology for cloning of tortoises has not yet been developed. Before we attempt cloning of Lonesome George, we feel we must exhaust all other possibilities first. There is the possibility that other tortoises could exist on George's native island of Pinta. Young tortoises are very small and secretive, and any young tortoises present when George was removed from Pinta would most likely have been overlooked. These tortoises would now be adults and technically easier to find, except that the vegetation of Pinta has responded vigorously to the removal of goats (which were previously destroying this vegetation.) The island is now very hard to get around, and a major campaign must be undertaken to systematically cover the island and definitively conclude that there are no remaining Pinta tortoises to use as a mate for Lonesome George. If our efforts are unsuccessful, when "Lonesome George" eventually dies, his race ends with him, and will join the other races of giant tortoise that have become extinct in the Galapagos. Heavy depredation by humans was the problem in the past. Today, one of the biggest problems facing the endemic Giant Galapagos tortoise is that of introduced species. The National Park Service and the Charles Darwin Research Station have eradicated the troublesome goat from Pinta. Many of the native plant species have recovered. There is hope for the recovery of Pinta as there is hope that one day we will find a mate for "Lonesome George" or another Pinta tortoise. If we can find a mate for Lonesome George, we'll be a long ways towards restoring the ecology of one of the most fascinating Galapagos Islands. Current data about "Lonesome George" Age: estimated to be 70-80 years Weight: 88kgs Size: 102 cm length of shell Health: No indication of any illness or disease (c) The Charles Darwin Foundation www.pettortoise.co.uk/lonesome_george.phpa nice photo of George  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 28, 2005 19:55:10 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 28, 2005 20:01:42 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 1, 2007 21:11:49 GMT

Scientists seek Lonesome George's tortoise kin

Reuters - Mon Apr 30, 6:51 PM ET

An undated file photo shows George, a giant Galapagos tortoise thought to be the last of his kind. REUTERS (Reuters)

By Julie SteenhuysenMon Apr 30, 6:50 PM ET

Lonesome George, a giant Galapagos tortoise thought to be the last of his kind, may not be so lonely after all, with the discovery of a possible cousin, researchers reported on Monday.

Lonesome George is famed for his status as the sole surviving member of a species of giant tortoise from Pinta Island, one of the Galapagos Islands off South America.

He has spent the last 35 years at the Charles Darwin Research Station on the island of Santa Cruz, sharing a pen with two similar-looking female tortoises from Pinta's neighbor, the volcanic island of Isabela.

But so far George has shown no interest in mating -- even though they brought in virile young males of the same species as the females to demonstrate.

"The future looked pretty bleak for Lonesome George up to now," said Adalgisa Caccone, a biologist at Yale University in Connecticut who helped lead the research.

Now, he might have a first cousin on Isabela, Caccone said in a telephone interview.

Caccone and colleagues at Yale have discovered a tortoise that is the offspring of a pure Pinta male that bred with a female on Isabela.

"This is the first time that an individual that carries as much as 50 percent of the genes from the same population (as) Lonesome George has been found," she said.

George's clan was driven to near-extinction by whalers in the 19th century, who hunted the tortoises for food, and later by the introduction of goats on the island, which ate up the tortoise's food and trampled their nesting grounds.

NATURAL SELECTION

George was discovered in 1972 and brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station. The tortoises on the Galapagos Islands, part of Ecuador, helped inspire Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection in the 1800s.

The Yale research, published in the journal Current Biology, relied on genetic material taken from museum samples of the Pinta tortoises, a species known as Geochelone abingdoni.

They matched that to a large database of genetic samples from all 11 existing species of Galapagos tortoises.

"We had this genotypic database for Pinta. With that data, we compared all of the individuals from our large database and bingo, we found this individual," Caccone said.

An exciting part of the finding is that the tortoise they found was the male offspring of a pure Pinta.

Now the search is on to find George's cousin, if he is alive, and any other close relatives.

"What we hope is that other tortoises from Pinta have survived as well," Caccone said.

She and colleagues hope to take a team of about 20 people back to Isabela for about a month to tag the population of about 1,000 tortoises and take blood samples from each -- no easy task for a creature that can weigh up to 400 pounds (200 kg).

Prospects of finding a suitable mate for George, who at 70 is still in his prime, are not yet clear, she said.

"This has now a ray of hope," she said. "Maybe he is not alone."

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Jun 6, 2007 22:35:19 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Jun 6, 2007 22:45:12 GMT

Pic found by Noisi  |

|

|

|

Post by aquaeyes11010 on Jun 8, 2007 2:12:18 GMT

As far as cloning is concerned, it wouldn't be terribly difficult to make an egg hatch out female. Reptiles (as far as I know, all of them) are without sex chromosomes. Gender is usually a result of incubation temperature. So after the hard task of creating a viable egg, one should be able to create different genders just by manipulating the incubator settings.

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Nov 18, 2007 0:32:47 GMT

Tortoise Genes and Island Beings

Giant Galápagos reptiles on slow road to recovery

Bryn Nelson

Not far from where the Galápagos Islands' most famous loner spends his days, tourists disembark by the inflatable boatload at a modern dock. A path takes them past marine iguanas sneezing brine from their salt-caked nostrils and striated herons roosting in the red mangroves to the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island. Within the station, another walkway leads to a natural enclosure sheltering a misanthropic Galápagos tortoise named Lonesome George.

The confirmed bachelor has been a potent icon of conservation ever since he was spotted on remote Pinta Island in 1971 and captured the next year by a group of goat hunters. Now in his 60s, 70s, or beyond—no one really knows—George may have lived more than half his life in exile. He is quite likely the world's last pure-bred Pinta tortoise, one of the dozen or so closely related species that still lumber around the Galápagos, an archipelago of 19 islands and dozens of islets about 600 miles west of mainland Ecuador.

Last April, however, the surprise discovery that Lonesome George has a genetic cousin on another island cast doubt, in a hopeful way, on George's one-of-a-kind status. The revelation is just one illustration of how genetics and conservation biology are intermingling to rewrite an oversize reptile's evolutionary past and to reshape plans to safeguard the remaining tortoise species well into the future.

Revival signs

Estimates of how many giant tortoises remain in the Galápagos vary widely, from less than 10,000 to more than 30,000. Nearly everyone agrees that their prospects are improving, however. "If you look at tortoises today compared to 50 years ago, they are so far ahead of where they used to be," says Linda Cayot, Lonesome George's former keeper and a scientific adviser to the Falls Church, Va.–based Galápagos Conservancy.

But tortoise conservation may be a rare bright spot in the struggle to protect the fragile Galápagos ecosystem. The archipelago is so revered for its unique marine and terrestrial life that it was the first World Heritage Site chosen by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In late June, the organization's World Heritage Committee added the caveat "in danger" to the designation to draw attention to mounting threats, including a surge in tourism and rising immigration from Ecuador's mainland. Increased flights and boat traffic have contributed to a 60 percent escalation in introduced species since 2001.

In April, before the UNESCO announcement, Ecuador's President Rafael Correa acknowledged these concerns by declaring the islands' ecosystem a national priority for conservation efforts. Amid the ensuing calls to scale back residency permits and overhaul a broken tourism model, the discovery of Lonesome George's kin sounded a rare hopeful note. Having compared highly variable regions of DNA from cell nuclei, Gisella Caccone and Jeffrey Powell of Yale University and their colleagues reported in the May 1 Current Biology that a tortoise on volcano-studded Isabela Island has about half its genes in common with George. The researchers even suggested that George may have full relatives on the same island.

The potential salvation of George's species, the Pinta tortoise, began in 1994. That year, the Yale team collected blood from 27 tortoises living on the slopes of mile-high Volcán Wolf, an active volcano on Isabela Island's northern end. Unlike single-species populations found elsewhere in the Galápagos Islands, the Volcán Wolf tortoises display an unusual combination of carapace shapes. Some are dome shaped, others have Lonesome George's distinctive saddle-back form, and some show characteristics of both types.

By 2002, the researchers had retrieved enough nuclear DNA and maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA from other Galápagos populations to tease out some unexpected links. The Volcán Wolf group seems to include a hodgepodge of lineages arising from multiple colonizations, while Lonesome George appears most evolutionarily related to saddle-backed tortoises on Española and San Cristóbal Islands, more than 180 miles to the southeast. Caccone speculates that some tortoises on the southern islands may have floated on the strong ocean currents that flow northwest to Pinta.

In 2003, a joint expedition by the Galápagos National Park and the Oviedo, Fl.–based Chelonian Research Institute failed to find any signs of tortoise life on Pinta Island but did uncover the skeletons of 15 former male residents. By extracting DNA from those remains and from others stashed away in museum collections, Caccone and her collaborators were able to compile a robust genetic profile of the Pinta species. Later, the researchers found a partial match in the nuclear DNA of a young male tortoise from the previously sampled Volcán Wolf population. The tortoise's mitochondrial DNA indicated that his mother had been born on Isabela. But it was clear that he had a Pinta male for a father, making him a hybrid of the two species.

"We had it all along but didn't know it until we had the new samples from Pinta," Caccone says. Because they have already uncovered one half-match among 27 Volcán Wolf tortoises out of a total estimated population of 2,000 to 8,000, she says, that "the chance of finding another hybrid, or even a pure [Pinta], is pretty high."

Caccone hopes to send three teams back to the steep volcano to collect more tortoise-blood samples next summer. If DNA tests reveal the presence of pure-blood Pintas, researchers could set up a new breeding program.

Discovering more Pinta tortoises would be "thrilling," agrees Johannah Barry, president of the Galápagos Conservancy, "but it would probably not be critical to the restoration of the Pinta Island ecosystem." Beyond the small chance of finding enough individuals to constitute a robust population, she says, back breeding any half-relatives to recover a pure Pinta bloodline could take decades.

How a Pinta father ended up on Isabela remains unclear. A strong current runs the roughly 50-mile route from Pinta to Volcán Wolf, and historical accounts leave open the possibility that tortoises may have washed ashore after being dumped overboard by pirates or whalers.

Genetic studies may allow researchers to reconstruct the history of specific tortoise populations and to determine whether they may have long-lost relatives on other islands. Even so, Caccone warns that genetic patterns are often deceptive within endangered species. Diverse genotypes, normally a hallmark of older populations, can be rapidly depleted through human interference and result in populations with artificially youthful profiles, she says.

Tortoise tales

Millions of years before Europeans first caught sight of the Galápagos in 1535, ancestors of the islands' tortoises were likely roaming the South American continent. Mitochondrial-DNA comparisons suggest that the small Chaco tortoise found in the southern half of South America is the closest living relative of its much larger Galápagos counterparts, although Caccone believes that their common ancestor was also oversize. A combination of genetic evidence and geological estimates of when the islands were formed suggests that tortoises likely arrived no more than 2 to 3 million years ago, she says.

As for how the animals made the 600-mile ocean voyage, the chilly Humboldt Current that flows north from the tip of South America and then west along the equator could have been a conduit. "It's a great highway," Caccone says. Whether carried along on her own or on a floating mat of vegetation, a single female laden with eggs could have founded the entire Galápagos population.

Apart from their size and buoyancy, Galápagos tortoises can stay alive for 6 to 9 months without food or water, an evolutionary adaptation that became a curse when 17th- and 18th-century buccaneers and subsequent waves of whaling crews discovered that the reptiles would provide a plentiful and long-lasting source of meat. The logbooks of whaling ships record crew members often loading tortoises by the dozens into bilges and cargo holds, including up to 100 Pinta tortoises at a time.

At least two species went extinct. And by the early 1900s, American and British researchers had retrieved only a handful of live tortoises on Pinta, all of which were killed by the collectors or died en route to distant museums. The fate of the Pinta population remained murky until 1971, when a snail expert conducting research on the island saw a single tortoise and took a few pictures, unaware that his sighting was anything unusual. Peter Pritchard, director of Chelonian Research Institute, recalls that the researcher casually mentioned his sighting when the two were dining together. "Well, I was flabbergasted," Pritchard says.

Eventually, word reached the Charles Darwin Foundation, which receives its funding from a range of nonprofit organizations, countries, and individual donors and advises the Ecuadorean government on conservation issues. The foundation's research station launched an expedition in early 1972. Pritchard, who was studying marine turtles at the time, joined the trip to look for turtle nesting sites. By the time his boat arrived, he says, a resourceful student had already found the Pinta tortoise, and the expedition's goat hunters had tethered it to a cactus so that it wouldn't disappear.

Moving forward

In the 35 years since then, Lonesome George has been living at the research station on Santa Cruz, spurning two female tortoises from Isabela, ignoring frisky males who have provided sex-ed lessons, and spurring a barrage of speculation over what ails him in the reproduction department.

George's keepers have looked into diet, erectile dysfunction, and other bodily functions but have yet to find an answer. Nor do researchers know enough about reptile physiology to try cloning him. In 1994, Cayot learned a sperm-retrieval technique from a German zoo veterinarian and taught a Swiss volunteer how to fondle a rather ticklish George. "She could get the other tortoises to ejaculate in 15 minutes," Cayot recalls. "We worked with George for months and got nothing."

Pritchard says that he has a videotape of George "energetically chasing a female, mounting her, and getting pushed off as she goes under a low branch"—testament to his intact, if unrefined, libido. But if the bachelor tortoise can't, or won't, keep the bloodline going, Caccone hopes that her hunt for a living relative with a stronger inclination will let George off the hook.

In the meantime, conservationists have assisted the wild tortoises on Isabela and other islands with a massive effort to eradicate one of their worst enemies: feral goats. Introduced as a food source by whalers, fishermen, and settlers, goats can chew plants down to the nub. Large herds can tear up the landscape, leading to severe erosion and even ecological collapse. On Isabela Island, goats didn't arrive until the 1970s. Less than 3 decades later, their ranks had swollen to an estimated 75,000 to 125,000.

Project Isabela, run jointly by the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Galápagos National Park, employed helicopters, hunters, and trained dogs to track down the island's unwelcome interlopers. The collaborators also fitted female "Judas goats" with radio collars to betray the locations of male admirers. Last year, researchers announced that the northern part of Isabela was goat free, adding to earlier successes on Pinta, Santiago, and Española Islands.

On Española, a tourist favorite in the archipelago's southern reaches, goats were removed by the thousands in the 1970s, but by then the island's resident tortoise population had dwindled to 12 females and 2 males. Volunteers evacuated the survivors to the Charles Darwin Research Station and set up an emergency breeding program. A third male from Española was later located at the San Diego Zoo and called into service. Remarkably, they and their repatriated descendants now number more than 1,400.

Tortoise-breeding centers are operating on the islands of Santa Cruz, Isabela, and San Cristóbal. At 5 years of age, most tortoises are too large to be threatened by invasive black rats and Norway rats, and can be resettled on their native islands with about an 80 percent survival rate. The Galápagos Conservancy's Barry says that the impressive track record should be a model for other resource-limited locations. "I think that restoring what we had a hand in removing is a fairly nice spin of the cosmic wheel," she says.

Success in culling the goats has not only made Pinta Island safe for tortoises again but has also intensified calls for their return. Without a major herbivore to break up the vegetation and regulate access to sunlight, botanists fear a loss of diversity among native plants and habitats and have lobbied for a full-scale tortoise reintroduction.

Officially, the Charles Darwin Foundation is neutral on the proposal, though Bryan Milstead, its head of vertebrate research, is leaning in favor of it. Tortoises are the major herbivores in the Galápagos and vital regulators of the ecosystem, he says. If Lonesome George cannot sire a new generation of tortoises for Pinta Island, Caccone's genetic research has shown that "the next best thing would be to bring an Española tortoise there."

Caccone hopes to repopulate Pinta Island with its native species, whether by George or a relative, though she concedes that much will depend on what her team finds on Isabela. She has a precedent, though, for believing that her DNA comparisons may turn up the unexpected. Two years ago, Caccone's team discovered the genetic signatures of three separate lineages on Santa Cruz instead of its presumed single species. Among their finds, the researchers determined that an isolated dome-shelled group of about 100 tortoises known by their geographic location, Cerro Fatal, should be considered a new species and added to the radar of conservationists.

As one species comes into being, taxonomically speaking, conservationists are struggling to keep hundreds of other types of native plants and animals from disappearing. Critically endangered mangrove finches are being terrorized by rats. Any importation of the West Nile virus could decimate the Galápagos penguin population. And guavas are among the hundreds of introduced plants that now far outnumber native ones.

Park officials are still grappling with tortoise poaching in some remote areas of Isabela, and they are reviewing a plan to kill invasive rats that eat native-born hatchlings on Pinzón and other islands. Even so, the evolutionary icons that so intrigued Charles Darwin are adapting better than many other Galápagos species. Although the guava is overtaking native plants, its fruit is fast becoming a favorite among the tortoises. "They're tough beasts, as long as people don't roll them over and chop them open," Pritchard says.

Like Pinta's potentially lost population, tortoises on San Cristóbal were once given up for dead. But on a trip to San Cristóbal in June, Pritchard's group counted 128 tortoises in 4 hours. "Give them a chance," he says, "and they will recover."

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 26, 2008 18:17:22 GMT

Famous Galápagos Tortoise, Lonesome George, May Not Be Alone ScienceDaily (May 1, 2007) — "Lonesome George," a giant Galapagos tortoise and conservation icon long thought to be the sole survivor of his species, may not be alone for much longer, according to a multinational team of researchers headed by investigators at Yale University.  Lonesome George at the Charles Darwin Research Station. (Credit: Alison Llerena/CDRS) New research led by biologists Adalgisa Caccone and Jeffrey Powell in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale, with the strong support and cooperation of the Galápagos National Park and Charles Darwin Research Station, has identified a tortoise that is clearly a first generation hybrid between the native tortoises from the islands of Isabela and Pinta. That means, this new tortoise has half his genes in common with Lonesome George. According to the Guinness Book of World Records Lonesome George, a native of Pinta, an isolated northern island of the Galápagos, is the "rarest living creature." By the late 1960s, it was noted that the tortoise population on this island that is visited only occasionally by scientists and fishermen, had dwindled close to extinction, and in 1972, only this single male of the species Geochelone abingdoni was found. Lonesome George was immediately brought into captivity at the Charles Darwin Research Station on the island of Santa Cruz where he is housed with two female tortoises from a species found on the neighboring island of Isabela. "Even after 35 years, Lonesome George seems uninterested in passing on his unique genes and has failed to produce offspring," said lead author Michael Russello of the University of British Columbia Okanagan who began working with the tortoises as a postdoctoral fellow at Yale. "The continuing saga surrounding the search for a mate has positioned Lonesome George as a potent conservation icon, not just for Galápagos, but worldwide." Although Lonesome George has yet to find a tortoise partner, upwards of 50,000 people visit him each year. The study, published in Current Biology, gives a peek into the evolutionary history of a species of Galápagos tortoise (G. becki) -- previously known to be genetically mixed --on the neighboring island of Isabela. The results were possible only with advances in technology from these researchers that make DNA from ancient or museum specimens useful for genetic analysis. Population analyses of a large database including individuals from all 11 existing species of Galápagos tortoises was compared to the genetic variation within two of the G. becki populations. DNA data for the nearly extinct G. abingdoni species from Pinta was available for the first time from six museum specimens -- and from Lonesome George. There are well over 2,000 tortoises of G. becki living on the neighboring volcanic Isabela Island, which has only two sites accessible from the sea. The research team collected samples from a total of 89 tortoises -- 29 at one location, 62 on the other side of the island. Because the subset of the population they sampled was so small, the researchers hope that thorough sampling will locate a genetically pure Pinta tortoise. The authors speculate that, in the event additional individuals of pure Pinta ancestry are discovered, a captive breeding and repatriation program could be set up for species recovery. "It will take a team of about 20 people about three to four weeks to do a first, exhaustive sampling and transmitter-tagging of the tortoises on the volcano," said Caccone. "Then once individuals of interest are found -- either hybrids with Pinta or pure Pinta animals -- an equivalent field expedition will have to be mounted to find the animals and bring them in captivity. But, it is a harsh environment with no local resources and funding such an operation will be costly." According to Powell, "These findings offer the potential for transforming the legacy of Lonesome George from an enduring symbol of rarity to a conservation success story." Other authors on the paper are Nathan Havill from Yale, Luciano B. Beheregaray from Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, James P. Gibbs from the State University of New York at Syracuse and Thomas Fritts from the University of New Mexico. The research was supported by the Bay Foundation, the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies and the National Geographic Society. Citation: Current Biology (May 1, 2007 -- early online) Adapted from materials provided by Yale University, via EurekAlert!, a service of AAAS. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/04/070430123849.htm |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Jul 23, 2008 22:34:07 GMT

'Lonesome George' to become a father? Updated 14.17 Wed Jul 23 2008 Keywords: tortoise, George A last-surviving tortoise of his kind may be about to become a father for the first time. George, who is believed to be between 60 and 90 years old, should still be in his sexual prime. But to the frustration of conservationists who want to save his species from becoming extinct, he has shown little interest in reproducing. He is a conservation icon in the Galapagos islands but now he may be about to become a father after keepers recovered a clutch of eggs from his enclosure. It will take about four months to know whether the eggs bear George's offspring. Jeff Powell, a professor of ecology at Yale University who has worked on giant tortoises in the Galapagos, added: "This is great news. The females have been with George for a long time, so if the eggs are fertilised, they will surely be his offspring." © Independent Television News Limited 2008. All rights reserved. itn.co.uk/news/738886169e22578fac1dbff662930362.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 24, 2008 7:17:34 GMT

Do we know is this female a Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni or another subspecies or a hybrid with some Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni x another subspecies?

|

|

|

|

Post by amongthylacines on Jul 24, 2008 10:36:22 GMT

Environment: Fabled bachelor Lonesome George may finally be a fatherIan Sample, science correspondent The Guardian, Wednesday July 23 2008 Lonesome George, the conservation icon of the Galapagos islands and last surviving tortoise of his kind, may finally become a father, after keepers recovered a clutch of eggs from his enclosure. Rangers at Galapagos National Park noticed George was behaving differently in recent months, and two weeks ago spotted one of his two female companions digging around in the soil in his pen. On closer inspection, they discovered a nest containing nine eggs, three of which they transferred to an incubator. It will be 120 days before they are able to confirm whether the eggs are harbouring George's offspring. George was rescued in 1972 from Pinta, one of the islands off Ecuador's Pacific coast, but has shown little interest in reproducing, much to the dismay of weary ecologists who are keen to prevent his species from becoming extinct. The tortoise, the world's rarest creature, became famous after fishermen and pirates slaughtered the rest of his species for food. If the eggs hatch and are proven to be George's offspring, it will represent a landmark success for conservationists, who are keen to rescue the species from imminent demise and re-establish the tortoises on Pinta. Giant tortoises were once the largest herbivores on the island, and in their absence plant life has continued to grow unchecked. The two females George shares his pen with are from the nearby volcanic island of Isabela, so any offspring will have only half the genes of a Pinta tortoise. It would take a breeding programme several generations - and possibly more than 100 years - to recreate a "pure" Pinta, scientists said. Henry Nicholls, author of the 2006 book Lonesome George: The Life and Loves of a Conservation Icon, said tortoises often lay unfertilised eggs, in much the same way as hens do, but the fact that rangers had moved several to an incubator was a promising sign. "There have been rumours of him mounting females, but nobody has ever witnessed penetration by George," he said. "Right now, we don't even know if George is fertile." Conservationists have tried a variety of methods to get the tortoise to mate, including artificial insemination, manual stimulation and having George watch younger males mate. George, who is believed to be between 60 and 90 years old, should still be in his sexual prime. Nicholls said even if the eggs are not fertilised, George's keepers should dissect them to see if they could find any sperm, a sign at least that George may not be infertile. Jeff Powell, a professor of ecology at Yale University who has worked on giant tortoises in the Galapagos, added: "This is great news. The females have been with George for a long time, so if the eggs are fertilised, they will surely be his offspring." Source: www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/jul/23/wildlife.animalbehaviour. guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2008

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 24, 2008 17:28:11 GMT

Thanks amongthylacines for the info

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Aug 8, 2008 19:58:17 GMT

That is indeed good news. Than the genetics of his subspecies will at least be (partly) preserved in his hybrid offspring. Here a video on this story on National Geographic News: video.nationalgeographic.com/video/player/news/latest-news/tortoise-george-apvin.htmlAugust 7, 2008—The last of his species, the giant tortoise Lonesome George has fertilized 11 eggs with 2 females at his home on one of the Galápagos Islands, scientists say. © 2008 National Geographic (AP) |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Aug 8, 2008 20:11:21 GMT

Do we know is this female a Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni or another subspecies or a hybrid with some Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni x another subspecies? Lonesome George = Pinta Island (or Abingdon Island) Tortoise, Geochelone nigra abingdoniHis two female enclosure mates = Volcán Wolf Tortoise (Northern Isabela Island), Geochelone nigra beckiTheir possible future hybrid offspring = Geochelone nigra abingdoni x Geochelone nigra becki |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 8, 2008 20:32:34 GMT

Thanks Peter for answering my question

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 19, 2008 19:31:00 GMT

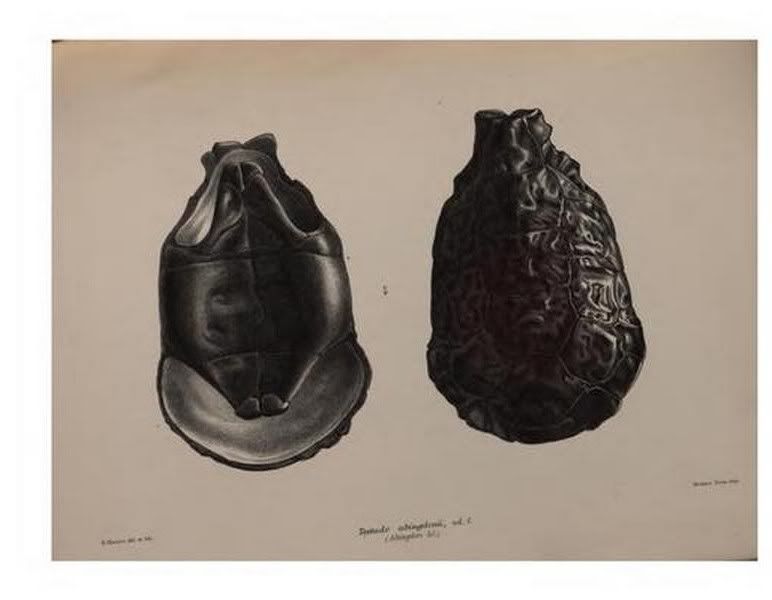

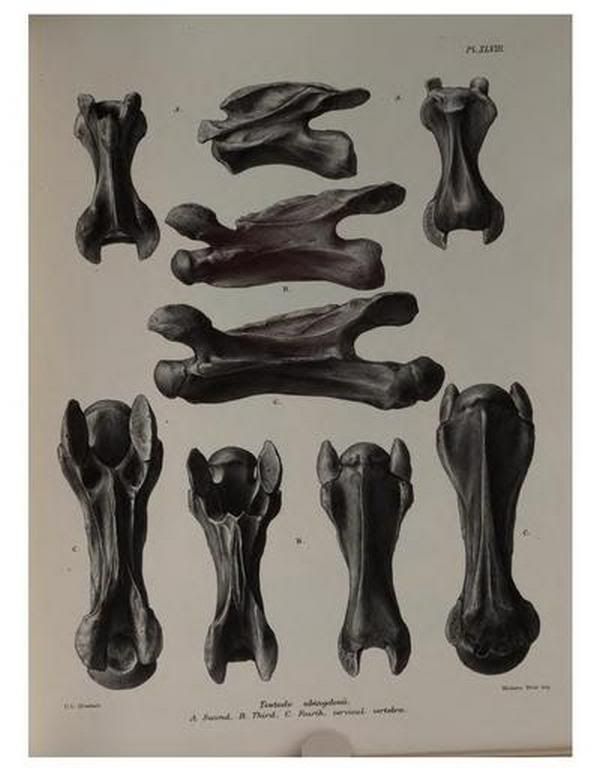

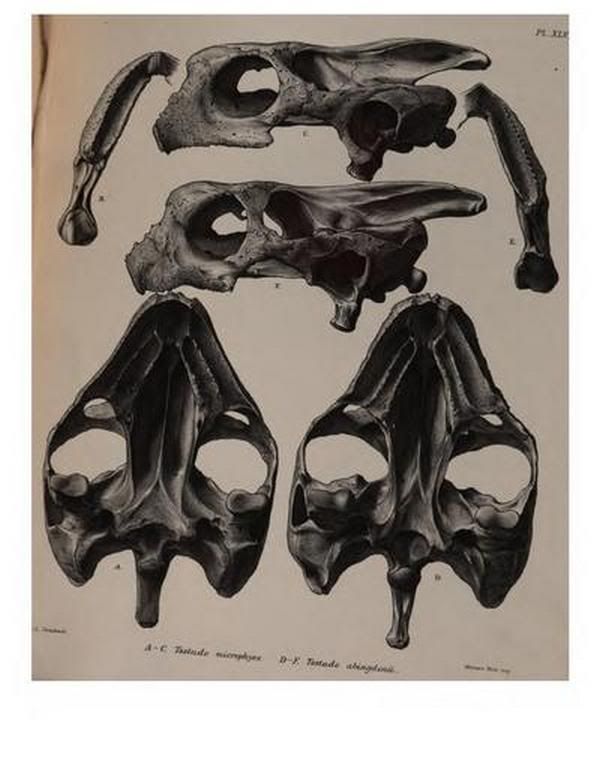

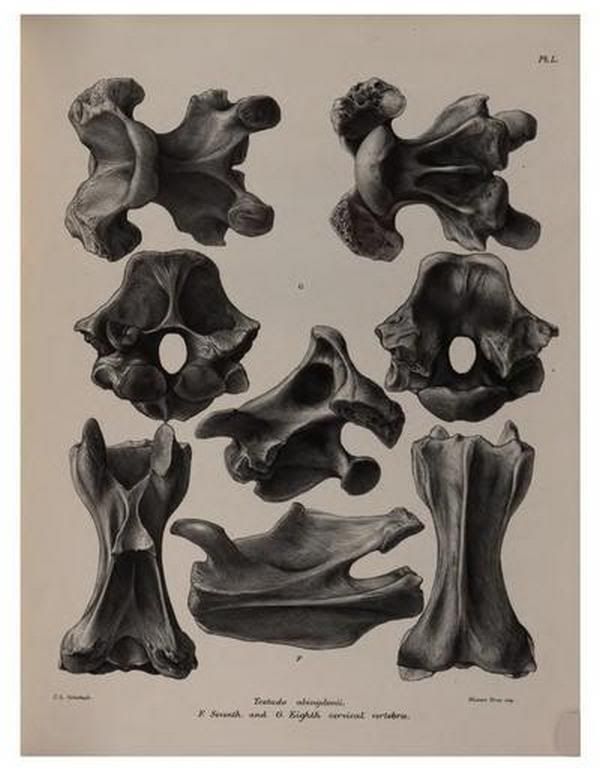

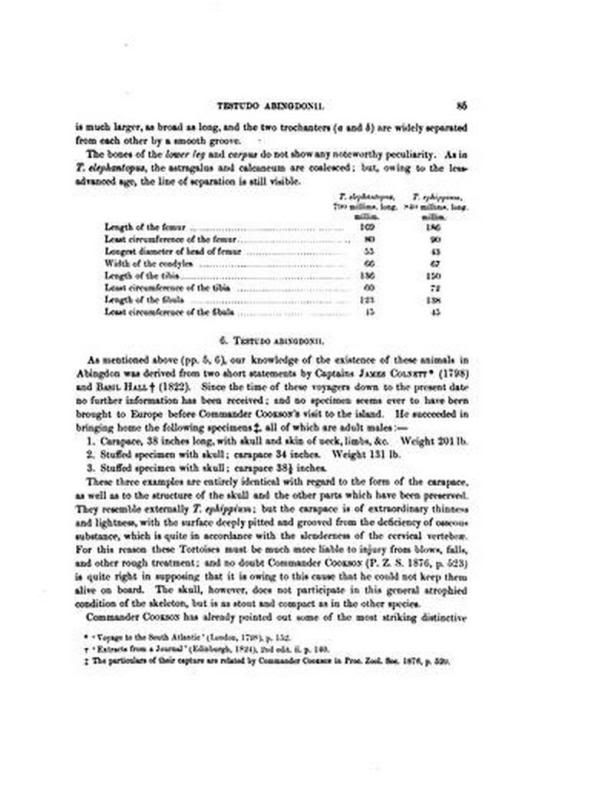

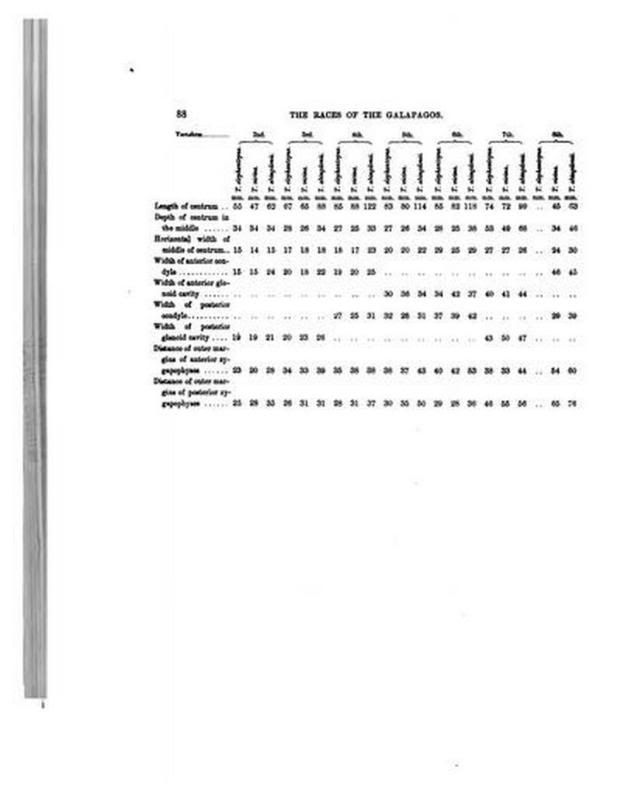

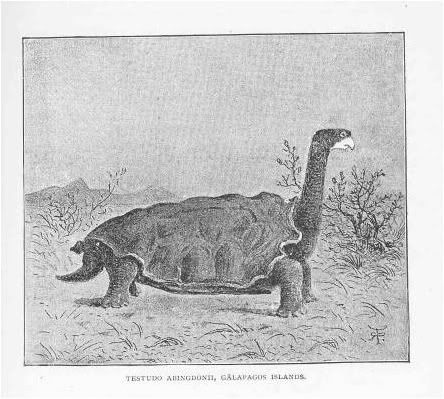

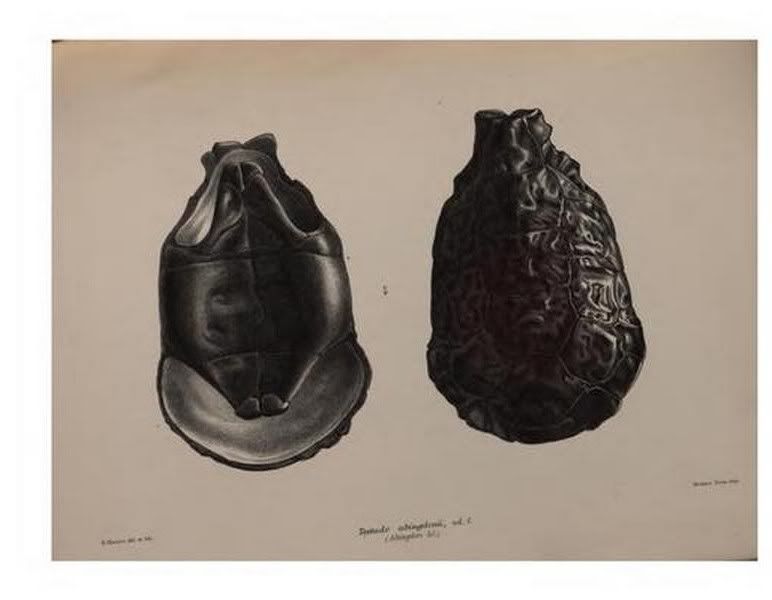

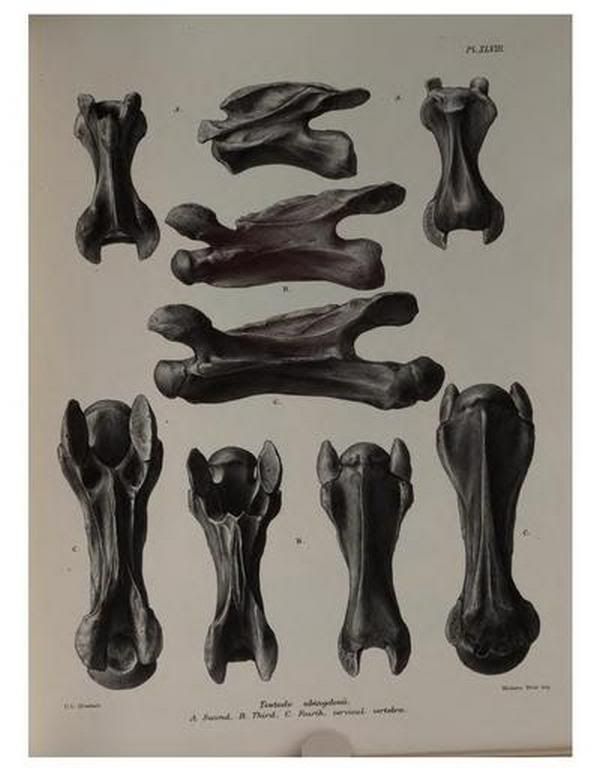

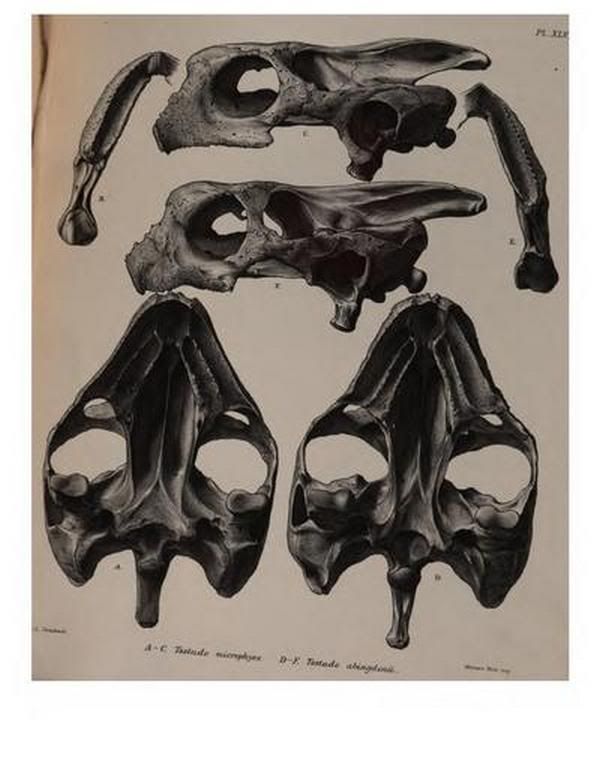

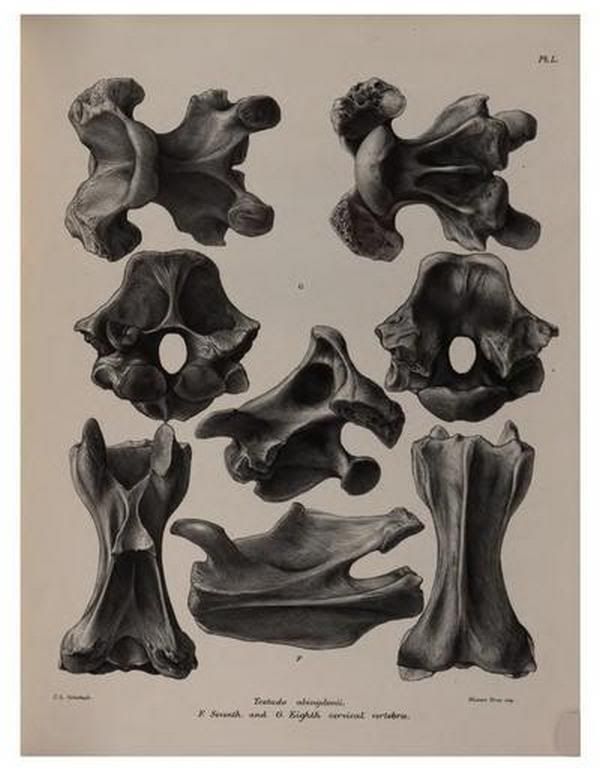

The Gigantic Land-tortoises (living and Extinct) in the Collection of the British Museum [microform] (1877) Author: Albert Carl Ludwig Gotthilf G̀eunther , British Museum . (Natural History ). Dept. of Zoology Publisher: Printed by order of the Trustees Year: 1877     |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 19, 2008 19:55:35 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Dec 21, 2008 14:08:11 GMT

Lonesome George's first sex in decades ends in disappointment Lonesome George, the conservation icon of the Galapagos islands and last surviving tortoise of his kind, is set to stay lonely – at least for the time being. By Louise Gray, Environment Correspondent Last Updated: 5:22PM GMT 06 Dec 2008 Lonesome George's first sex in decades ends in disappointment Lonesome George became unexpectedly amorous with a female subspecies - but the resulting eggs are not looking healthy Photo: AFP/GETTY IMAGES The 90-year-old raised hopes earlier in the summer when he successfully mated with two female tortoises of another subspecies after decades of disinterest in the other sex. The resulting batch of around a dozen eggs caused excitement around the world that Lonesome George had ensured the survival of his species. However hope began to fade when park rangers reported the eggs were losing weight and not looking good. Now disappointed scientists have announced that all the eggs are infertile. But this week has brought some cause for hope. A tortoise called Jonathan on the South Atlantic island of St Helena has been revealed to be at least 176 years old after a photograph was found showing the creature beside prisoners of the Boer War. What is more Jonathan regularly mates with three younger females on the island, according to locals. At the relatively young age of 90, George could have many years of sexual activity before him and scientists are already looking for another prospective mate. Lonesome George has become a cause célèbre for conservationists around the world since he was found in 1971, the last known member of the Pinta Island tortoise subspecies (Geochelone nigra abingdoni). During his decades in captivity, George had showed little interest in sex, but he surprised rangers earlier this year when he mated with a female of a different subspecies. His new-found libido raised hopes he could save his subspecies from extinction. The eggs were laid three months ago and placed in incubators, decorated with religious images by rangers in the hope of a miracle. However, the eggs showed signs of infertility early on and staff at the Galapagos National Park have now declared no embryos have developed. The Galapagos National Park director general, Sixto Naranjo, said George could be sterile, or else the female's adjustment to captivity could have left them infertile. Another possibility is that the diet in their breeding centre negatively affected their reproductive systems, he said. But conservationists have vowed to continue trying. A team of seven biologists and 26 park rangers have begun taking blood samples from tortoises on nearby Isabela Island in search of hybrid species that share as many or more genes with Lonesome George and could provide a new girlfriend – and a rare species with another chance. www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/wildlife/3566021/Lonesome-Georges-first-sex-in-decades-ends-in-disappointment.html |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Dec 21, 2008 14:10:00 GMT

|

|