Post by sebbe67 on Apr 19, 2005 13:17:45 GMT

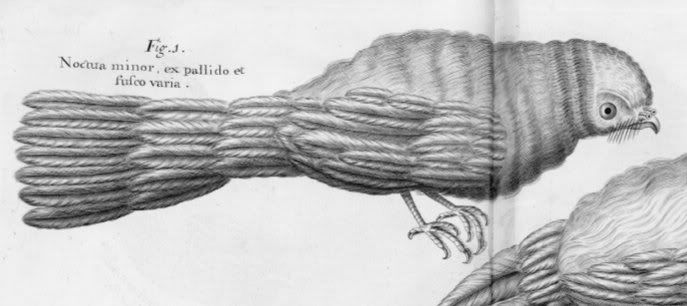

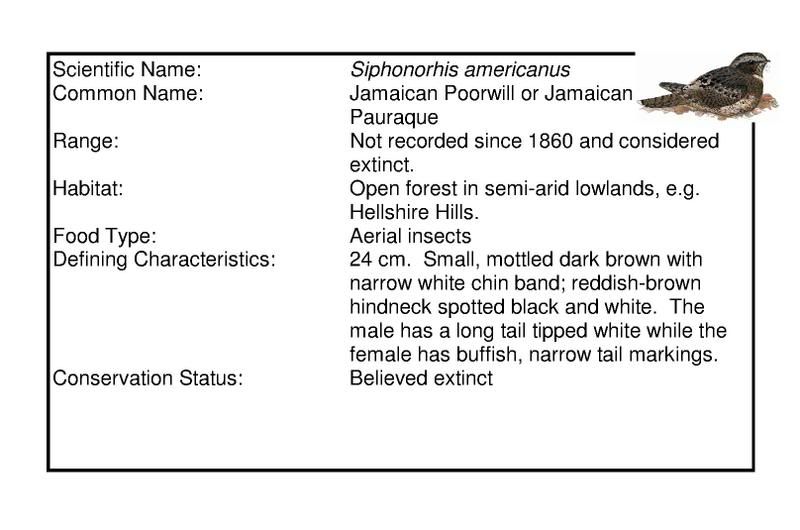

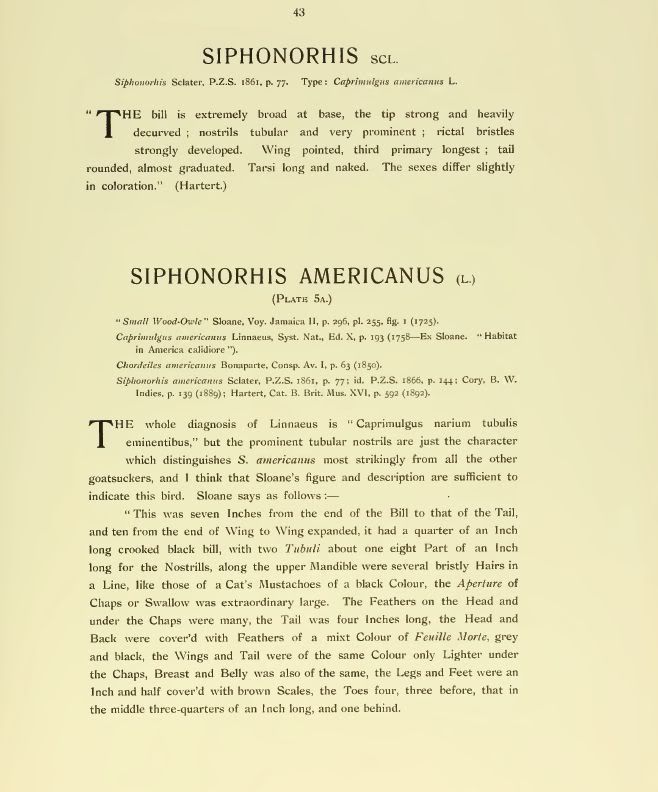

Siphonorhis americanus

DISTRIBUTION

This species is endemic to Jamaica and is apparently known from just three specimens, all taken before 1860 (Greenway 1958). The localities, which are spread throughout the island, are (from west to east): Savanna-la-Mar (in the Bluefields area) in Westmoreland, where a male (in BMNH) was collected in August 1858 (Osburn 1859, Greenway 1958, Sutton 1981); Freeman's Hall near Albert Town in Trelawney, where a female (in BMNH) was taken in September 1859 (Bond 1956b, Greenway 1958, Sutton 1981); and near Linstead, St Thomas-in-the-Vale (the Worthy Park area of St Catherine), where one of a pair was collected (March 1863, Sutton 1981: see Remarks); the St Catherine Hills themselves were identified as a general area of occurrence by March (1863).

Recent unconfirmed reports (i.e. of birds that could not be ascribed to either of the two other caprimulgids on the island) include: a bird seen several times on one night during February 1975 in the Portland Ridge area (Sutton 1981); and one seen at Milk River in the 1980s (Reynard 1988: see below).

POPULATION

The former status of the Jamaican Pauraque is essentially unknown, March (1863) simply reporting it to be "often met with in the St Catherine Hills". Greenway (1958) suggested that it must always have been localized, and Fuller (1987) that it was extremely rare even at an early date, both authors using the fact that the bird was unknown to P. H. Gosse (or his acquaintances) between 1830 and 1840 to justify their conclusions. However, the testimony of March (1863) cited above suggests that historically it was at least locally not uncommon.

As the last record was of a specimen taken in 1859 or 1860, this bird has long been considered possibly or probably extinct (e.g. Sclater 1910, Bangs and Kennard 1920, Greenway 1958, Bond 1979), but the same authors also admit the possibility that a population still exists somewhere on the island. There have indeed been a small number of unconfirmed recent reports: a bird seen in the Portland Ridge area in February 1975 had plumage and physical characteristics incompatible with the other two caprimulgids on the island (Sutton 1981), although it now seems likely that it was a Common Potoo Nyctibeus griseus (C. Levy in litt. 1992); a bird was seen at Milk River (Reynard 1988); and a hunter in Hellshire Hills described a caprimulgid that appeared likely to be this pauraque (N. Varty in litt. 1990).

ECOLOGY

Very little is known of the ecology of the species, none of the collectors or observers noting anything referring to habitat or behaviour. Bond (1979) intimated that it occurred (or may still occur) in semi-arid woodland such as in the Hellshire Hills, and AOU (1983) extended this, claiming that it was (or is) a bird of scrubby woodland and partly open situations in arid or semi-arid country: both these statements appear to be based on the habitat requirements of the closely related Least Pauraque Siphonorhis brewsteri. The three collecting localities where the species has been taken indicate that it is or was perhaps one of taller forest (see Sutton 1981): however, all the recent unconfirmed records have come from the semi-arid areas along the south coast (see above). Lack (1976) averred that it formerly occurred in lowland woodland, its relatively short wings and tail suggesting that it hunted amongst trees and not in the open. Bangs and Kennard (1920) concluded that it undoubtedly nested on the ground.

THREATS

The mongoose Herpestes auropunctatus was introduced onto the island during 1872 (Bond 1956b), and Bangs and Kennard (1920) judged that as the bird "undoubtedly nested on the ground... [it] probably fell an easy prey to the mongoose". Greenway (1958) reinforced the idea that introduced mammal species were responsible for the extirpation of this bird, but noted that since the mongoose was not introduced until 1872, it can be assumed that rats Rattus spp. were the cause of any decline prior to this date. As it is apparently unknown exactly which habitat type the species preferred, the threat from habitat destruction is difficult to assess. However, the loss of at least 75% of the original forest cover on Jamaica, with remaining forest largely secondary in nature (Haynes et al. 1989) presumably had (and perhaps continues to have) an adverse effect: deforestation continues at a rate of 3.3% per year (Eyre 1987, Varty 1991). The threat of habitat destruction was further exacerbated in 1988 when much of remaining forest was damaged by Hurricane Gilbert (Varty 1991), although dry limestone forest was relatively unaffected and occurs at two sites, namely Hellshire Hills and Portland Ridge (Vogel and Kerr in press).

MEASURES TAKEN

None is known. The first two Jamaican national parks (one marine and one terrestrial) are being established, although neither includes habitat suitable for this species (N. Varty verbally 1992). The recent rediscovery of a small population of the Jamaican Iguana Cyclura collei has led to fieldwork being concentrated in dry limestone forest, during which the pauraque is being searched for (with assistance from the Gosse Bird Club) (C. Levy in litt. 1992).

MEASURES PROPOSED

The major priority for conservation in Jamaica must be the control of deforestation (Varty 1991), and before specific measures can be outlined for the Jamaican Pauraque, the species has to be rediscovered and an assessment of its ecological requirements made. Only when this has been done can specific areas or habitat types be proposed for protection.

DISTRIBUTION

This species is endemic to Jamaica and is apparently known from just three specimens, all taken before 1860 (Greenway 1958). The localities, which are spread throughout the island, are (from west to east): Savanna-la-Mar (in the Bluefields area) in Westmoreland, where a male (in BMNH) was collected in August 1858 (Osburn 1859, Greenway 1958, Sutton 1981); Freeman's Hall near Albert Town in Trelawney, where a female (in BMNH) was taken in September 1859 (Bond 1956b, Greenway 1958, Sutton 1981); and near Linstead, St Thomas-in-the-Vale (the Worthy Park area of St Catherine), where one of a pair was collected (March 1863, Sutton 1981: see Remarks); the St Catherine Hills themselves were identified as a general area of occurrence by March (1863).

Recent unconfirmed reports (i.e. of birds that could not be ascribed to either of the two other caprimulgids on the island) include: a bird seen several times on one night during February 1975 in the Portland Ridge area (Sutton 1981); and one seen at Milk River in the 1980s (Reynard 1988: see below).

POPULATION

The former status of the Jamaican Pauraque is essentially unknown, March (1863) simply reporting it to be "often met with in the St Catherine Hills". Greenway (1958) suggested that it must always have been localized, and Fuller (1987) that it was extremely rare even at an early date, both authors using the fact that the bird was unknown to P. H. Gosse (or his acquaintances) between 1830 and 1840 to justify their conclusions. However, the testimony of March (1863) cited above suggests that historically it was at least locally not uncommon.

As the last record was of a specimen taken in 1859 or 1860, this bird has long been considered possibly or probably extinct (e.g. Sclater 1910, Bangs and Kennard 1920, Greenway 1958, Bond 1979), but the same authors also admit the possibility that a population still exists somewhere on the island. There have indeed been a small number of unconfirmed recent reports: a bird seen in the Portland Ridge area in February 1975 had plumage and physical characteristics incompatible with the other two caprimulgids on the island (Sutton 1981), although it now seems likely that it was a Common Potoo Nyctibeus griseus (C. Levy in litt. 1992); a bird was seen at Milk River (Reynard 1988); and a hunter in Hellshire Hills described a caprimulgid that appeared likely to be this pauraque (N. Varty in litt. 1990).

ECOLOGY

Very little is known of the ecology of the species, none of the collectors or observers noting anything referring to habitat or behaviour. Bond (1979) intimated that it occurred (or may still occur) in semi-arid woodland such as in the Hellshire Hills, and AOU (1983) extended this, claiming that it was (or is) a bird of scrubby woodland and partly open situations in arid or semi-arid country: both these statements appear to be based on the habitat requirements of the closely related Least Pauraque Siphonorhis brewsteri. The three collecting localities where the species has been taken indicate that it is or was perhaps one of taller forest (see Sutton 1981): however, all the recent unconfirmed records have come from the semi-arid areas along the south coast (see above). Lack (1976) averred that it formerly occurred in lowland woodland, its relatively short wings and tail suggesting that it hunted amongst trees and not in the open. Bangs and Kennard (1920) concluded that it undoubtedly nested on the ground.

THREATS

The mongoose Herpestes auropunctatus was introduced onto the island during 1872 (Bond 1956b), and Bangs and Kennard (1920) judged that as the bird "undoubtedly nested on the ground... [it] probably fell an easy prey to the mongoose". Greenway (1958) reinforced the idea that introduced mammal species were responsible for the extirpation of this bird, but noted that since the mongoose was not introduced until 1872, it can be assumed that rats Rattus spp. were the cause of any decline prior to this date. As it is apparently unknown exactly which habitat type the species preferred, the threat from habitat destruction is difficult to assess. However, the loss of at least 75% of the original forest cover on Jamaica, with remaining forest largely secondary in nature (Haynes et al. 1989) presumably had (and perhaps continues to have) an adverse effect: deforestation continues at a rate of 3.3% per year (Eyre 1987, Varty 1991). The threat of habitat destruction was further exacerbated in 1988 when much of remaining forest was damaged by Hurricane Gilbert (Varty 1991), although dry limestone forest was relatively unaffected and occurs at two sites, namely Hellshire Hills and Portland Ridge (Vogel and Kerr in press).

MEASURES TAKEN

None is known. The first two Jamaican national parks (one marine and one terrestrial) are being established, although neither includes habitat suitable for this species (N. Varty verbally 1992). The recent rediscovery of a small population of the Jamaican Iguana Cyclura collei has led to fieldwork being concentrated in dry limestone forest, during which the pauraque is being searched for (with assistance from the Gosse Bird Club) (C. Levy in litt. 1992).

MEASURES PROPOSED

The major priority for conservation in Jamaica must be the control of deforestation (Varty 1991), and before specific measures can be outlined for the Jamaican Pauraque, the species has to be rediscovered and an assessment of its ecological requirements made. Only when this has been done can specific areas or habitat types be proposed for protection.