Researchers can't confirm rediscovery of ivory-billed woodpecker

BY JOHN CREWDSON

Chicago Tribune

CHICAGO - Three seasons of searching still have not produced the icon that would forever settle the dispute: a single photograph of a clearly identifiable ivory-billed woodpecker.

"We probably wouldn't be truthful if we said we weren't a little disappointed. We've put a lot of effort into this," Cornell University researcher Ron Rohrbaugh said Thursday.

Last year Cornell researchers stunned bird-lovers everywhere by announcing that the ivory-bill had been rediscovered after 60 years, by happenstance, in an Arkansas swamp. Before that, the magnificent bird was thought to have vanished along with the stately hardwood forests of the southern United States where it had flourished for centuries.

Cornell, this nation's Citadel of ornithology in bucolic Ithaca, N.Y., said Thursday that it still believes the ivory-bill was spotted two years ago, but it no longer plans to go on spending $1 million a year, mostly from private donations but including some federal funds, to prove it. Critics say the inability to get a photograph of the bird supports their doubts about Cornell's original announcement.

Before it ended last month, the most recent effort to locate the woodpecker involved 20 full-time biologists and more than 100 amateur volunteers, plus all the technology Cornell could muster: automatic sound recorders and camouflaged time-lapse cameras hidden deep in the forest, laser rangefinders, GPS units, even ultralight aircraft.

The results: four "brief possible sightings"_ one by a volunteer searcher and three by "members of the public"_ but none by a Cornell staff member or other trained ornithologist.

Next year's search, if there is to be one, will rely mainly on volunteers, with Cornell sending in an "ivory-bill SWAT team" if anything interesting turns up.

Perhaps the surest sign that hope has ebbed was the concurrent announcement by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that the public, whose access to the area had been limited during the search, will now be allowed unrestricted admission.

This year's search also looked downward as well as up, in hopes of finding the kind of "roost hole" in a tree where ivory-bills are thought to reside. A "tree-by-tree" survey over a 12-mile radius found no ivory-bill nests, researchers said.

A few recordings of what might have been the ivory-bill's call, which sounds to some like the word "kent," are still undergoing analysis. One thing Cornell has learned is that other birds, particularly blue jays, who are notorious mimics, make sounds that are extremely difficult to distinguish from the only verified ivory-bill recording, which dates from 1935.

The ivory-bill story began in March 2004, when Cornell's Laboratory of Ornithology rushed troops to Arkansas' Cache River National Wildlife Refuge, not far from the town of Brinkley, to confirm a possible ivory-bill sighting by Tim Gallagher, the editor of the laboratory's magazine, who with a companion, Bobby Harrison, had been chasing an unconfirmed report on the Internet.

Since then the evidence for the ivory-bill's possible existence has diminished from seven "convincing sightings" in the spring of 2004, to a single such sighting during a more extensive search last year, to none in the search that concluded last month.

Thursday's cheerless announcement provided a striking counterpoint to the joyous news conference a year ago, when 10 Cornell researchers published a scientific report declaring that the ivory-bill, "long suspected to be extinct, has been rediscovered in the Big Woods region of eastern Arkansas."

Ornithologists were awe-struck. Some admitted having been reduced to tears. "I dreamed about the bird when I was a kid, about going to search for it, and I think a lot of ornithologists feel the same way," says Kenn Kaufman, author of the definitive book "Lives of North American Birds."

Princeton's David Wilcove, who only four years before had declared the ivory-bill extinct, spoke for many when he acknowledged that "sometimes it's great to be wrong."

Leaping to take advantage of the historic moment was the Bush administration, whose record on the ecology, including funding for endangered species, has disappointed many conservationists.

"A rare second chance," said then-Interior Secretary Gale Norton, beaming on the podium next to the Cornell lab chief, John Fitzpatrick. Her department, Norton said, was committing $5 million - a significant chunk of the budget for the protection of endangered species - to aid the recovery and preservation of the ivory-billed woodpecker.

As it has unfolded over the past turbulent year, the woodpecker's tale has proved to be about much more than a splendid bird with a massive, gleaming, ivory-colored bill and majestic wingspan of close to three feet, although it is surely about that.

As the Cornell article began to circulate among ornithologists, second thoughts were heard. Examined under a bright light, the evidence confirming the existence of a bird not officially seen in the U.S. since 1944 seemed to many a little thin.

A half-dozen lone observers, including several not trained as ornithologists, had reported seeing what they thought was an ivory-bill fly by, in most cases more than 100 yards away. But none had managed to photograph the bird.

At that point, recalled Jeff Wells, who helped coordinate logistics for the search, Cornell began deploying observers in teams of two, hoping that each would serve as a check on the other. Once the two-member teams were in the field, Wells said, the sightings ceased.

Wells recalls the day Gallagher returned to Ithaca with his breathless account of having seen the ivory-bill. "Naively, we all assumed well, he's right, and we'll go down and find it and verify it quickly," Wells said.

"They thought they had a confirmation," says J. Michael Reed, an associate professor of avian ecology and conversation biology at Tufts University in Massachusetts. "So I think they were trying to react quickly to take advantage of what would be a very popular finding. It was something that obviously grabbed the public imagination."

But the public imagination would have to wait. Everyone involved in the search had to sign a confidentiality agreement whose ostensible purpose was to prevent the area from being overrun with amateur birders. But the agreements also had the effect of keeping the search a secret from Cornell's academic competitors.

"We absolutely felt very uncomfortable with that whole process," says Wells. "We're not people who do that kind of thing. People who work in government or in the military, I guess, are used to that. But we aren't."

Yale ornithologist Richard Prum agrees. "It's a bad idea to take a bunch of people and put them in a situation where they can't talk to anybody except themselves for 13 months. There's not enough oxygen in the room for alternate opinions."

The best time of year for woodpecker-watching is from December through April, when the foliage is least dense and before the bayous are overrun with mosquitoes and poisonous snakes.

Near the end of the search window, at a quarter to four on the afternoon of April 25, 2004, somebody finally got a picture of a woodpecker: a shaky, blurry, four-second video, made by a video camera that had been left running in a swamp boat when a bird happened past.

But what bird?

"There definitely wasn't this `Hurrah' or `That's it,'" Wells recalled. "It was like `hmmmm.' We weren't sure what it showed, you know. I would say there was an agnostic attitude."

Its hopes for a clearer picture were dashed at that time, but Cornell nonetheless decided to publish its historic "rediscovery" in the prestigious journal Science, principally on the strength of the video.

With Thursday's announcement, the video remains the only visual record of what might have been an ivory-billed woodpecker.

In the nearly two years since it was made, the video has been dissected frame by fuzzy frame, first by the Cornell group and then by its critics. The results are reminiscent of "Rashomon," a celebrated 1950s Japanese film in which four witnesses give entirely different accounts of the same crime.

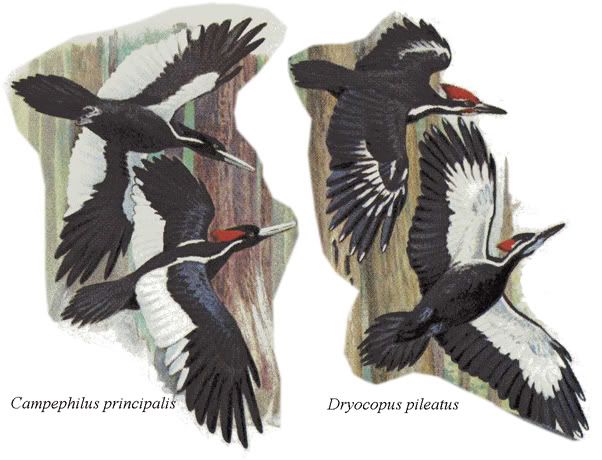

From a distance, the principal difference between the ivory-bill and the smaller, less dramatic and relatively much more common pileated woodpecker, is the amount and location of the white patches on its black-and-white wings.

The Cornell group sees an ivory-billed woodpecker. A growing number of opponents, many of whom spend their lives in the field searching for birds, see a pileated woodpecker.

Besides Kenn Kaufman, they include David Sibley, whose field guides are known to every birder and who reputedly can identify any North American bird "on the wing," and Bret Whitney, who is said to be able to do the same by listening to their songs and has discovered several new species this way.

"Why in the world didn't they pass this around to a wide circle of people, mainly expert birders, before they went public with it?" Whitney wonders now.

There have been other disputes in science as bitter as this one, but the bitterness is usually kept behind the scenes. In this case it has spilled forth to create an unpretty picture of scientific comity.

"Everyone is disheartened that the continuous expeditions have not found it again," says Jerome Jackson of Florida Gulf Coast University, who is acknowledged as the nation's leading expert on the ivory-billed woodpecker but was not invited to join the search.

In print, Jackson has attacked the Cornell paper on multiple technical grounds and accused Fitzpatrick's group of practicing "faith-based ornithology" and "marketing" its discovery.

"Sound bites must not pass as science," says Jackson, who worries that "If no ivory-billed woodpeckers are `found' in the Big Woods, will we have lost public trust and support for future conservation efforts?"

A few days ago Fitzpatrick and the Cornell group fired back in print, at Jackson's "factual errors and poorly substantiated opinions about our work."

Interviews with more than a score of those on both sides of the dispute were peppered with such words and phrases as "idiots," "garbage," "clowns" and "smoke and mirrors."

The critics say they are not just carping.

Funds for the preservation of endangered species were already stretched thin as the Iraq war and other events caused the federal deficit to rise. When Interior came up with $5 million to help a bird whose existence is evermore in question, it rankled biologists fighting to save threatened birds and animals that are known to exist.

"The $5 million," Richard Prum says, "is not new money," having been taken from already appropriated funds. "There's zero new money," Prum says. "Projects are being cancelled. Corners are being cut. Biologists are really upset about this."

"This year there was virtually no money," said a federal biologist responsible for saving a bird of which few people have heard, and who spoke only on condition of anonymity for fear of losing his job.

"My funding was cut completely last year," says a project manager in another part of the country who requested anonymity for the same reason. "We didn't just have a fuzzy videotape, we had the animals, and yet nobody really cared."