Post by Melanie on Nov 7, 2005 17:11:05 GMT

Deletion of the Flightless Ibis Xenicibis

from the Fossil Record of Cuba

WILLIAM SUA´ REZ Museo Nacional de Historia Natural;

Obispo 61, Plaza de Armas, La Habana CH 10100, Cuba.

geopal@mnhnc.inf.cu

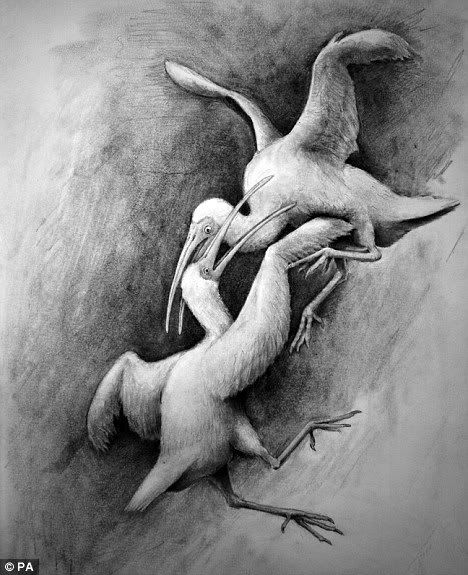

Shortly after the discovery of the first known flightless

ibis Apteribis glenos (Olson and Wetmore, 1976) in

the Hawaiian islands (augmented later by a second

species A. brevis Olson and James, 1991), the equally

remarkable flightless ibis Xenicibis xympithecus (Olson

and Steadman, 1977) was described from Jamaica. The

description was based on some postcranial elements

collected by H. E. Anthony during 1919-1920 in a cave

deposit at Long Mile Cave, Trelawny Parish, Jamaica,

and was followed by the description of a complete and

well preserved humerus from Swansea Cave, St.

Catherine Parish, Jamaica (Olson and Steadman,

1979).

That Xenicibis might have been more widely distributed

was suggested by Acevedo-Gonza´les and Arredondo

(1982), who recorded the genus from Cuba

without mentioning localities or specimens. Arredondo

(1984:6-7) then referred to “Xenicibis sp.” a

complete left humerus that he collected in Cueva de

Pý´o Domingo, Sumidero, Pinar del Rý´o, and kept in his

private collection (OA 2969). He also noted some other

appendicular elements of “Xenicibis sp.”, including the

distal end of a left tibiotarsus, a left tarsometatarsus,

and one phalanx, all uncataloged at the time but now

numbered OA 2970a, OA 2971, and OA 2972, respectively.

These bones were found in association with the

humerus, and the tarsometatarsus was described

briefly.

As part of my revisionary work on Arredondo’s paleontological

collection, I examined all of the above

material and found that it does not represent the genus

Xenicibis, nor any other ibis (Threskiornithidae).

Instead, these specimens agree in all their osteological

characters with Aramus guarauna, the Limpkin (Aramidae),

a gruiform structurally similar to primitive

cranes (see Olson 1985). Arredondo did not compare

his material with Aramus, and his identification of the

fossil specimens was based on comparisons with illustrations

of Xenicibis xympithecus (see Arredondo 1984).

The Limpkin is widely distributed in the Neotropics

and is fairly common in Cuba (Garrido and Garcý´a

Montan˜a, 1975). It occurs in other Greater Antillean

islands near bodies of water, rice fields, wooded floodplains

of rivers, and upland wet forest (Raffaele et al.,

1998:265).

The left humerus reported by Arredondo is inside

the range variation of a small series of skeletons of

Aramus guarauna from Cuba. It is partially covered by

travertine, showing wear on the pectoral crest, internal

tuberosity, and bicipital crest. The other referred specimens show some differences in color and degree

of mineralization in comparison with this last specimen.

The humerus of Xenicibis is characterized by a

slender twisted shaft, bicipital crest reduced, pectoral

crest reduced in area, thickened, and twisted; external

tuberosity reduced and displaced distally, with a very

deep and wide brachial depression (Olson and Steadman,

1979). None of these flightless characters occurs

in the Cuban humerus, which has a much shorter shaft

that is less curved latero-medially and not twisted and

flattened up to the mid point; the bicipital crest is well

developed and not reduced, and placed proximally;

the external tuberosity is more proximal and well defined,

not distal and reduced; the pectoral crest is large

and wide instead of short and thin.

None of the other bones show diagnostic characters

of the genus Xenicibis, such as very wide anterior intercondylar

fossa and reduced supratendinal bridge in

the tibiotarsus, or tarsometatarsus with two simple

calcaneal ridges well separated by a deep groove (Olson

and Steadman, 1977). In all respects these bones

agree with Aramus guarauna, particularly in having a

wide supratendinal bridge, a thin intercondylar sulcus

of the tibiotarsus, and a tarsometatarsus with closed

calcaneal ridges that form canals, among other characters.

However, these specimens represent the first

record of Aramus guarauna in Cuban Quaternary deposits.

The genus Xenicibis is known only in Jamaica, where

its flightlessness evolved. Water barriers that constantly

separated that island from Cuba throughout

geological history (see Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee,

1999) prevented the dispersal of this genus to Cuba.

Acknowledgements.—I thank Prof. Oscar Arredondo

for his assistance during the revision of his paleontological

collection. Gilberto Silva Taboada (Museo Nacional

de Historia Natural de Cuba) and Storrs L. Olson

(Smithsonian Institution) made valuable

comments on the first drafts of this manuscript.

www.uprm.edu/publications/cjs/Vol37a/37_109-110.pdf

from the Fossil Record of Cuba

WILLIAM SUA´ REZ Museo Nacional de Historia Natural;

Obispo 61, Plaza de Armas, La Habana CH 10100, Cuba.

geopal@mnhnc.inf.cu

Shortly after the discovery of the first known flightless

ibis Apteribis glenos (Olson and Wetmore, 1976) in

the Hawaiian islands (augmented later by a second

species A. brevis Olson and James, 1991), the equally

remarkable flightless ibis Xenicibis xympithecus (Olson

and Steadman, 1977) was described from Jamaica. The

description was based on some postcranial elements

collected by H. E. Anthony during 1919-1920 in a cave

deposit at Long Mile Cave, Trelawny Parish, Jamaica,

and was followed by the description of a complete and

well preserved humerus from Swansea Cave, St.

Catherine Parish, Jamaica (Olson and Steadman,

1979).

That Xenicibis might have been more widely distributed

was suggested by Acevedo-Gonza´les and Arredondo

(1982), who recorded the genus from Cuba

without mentioning localities or specimens. Arredondo

(1984:6-7) then referred to “Xenicibis sp.” a

complete left humerus that he collected in Cueva de

Pý´o Domingo, Sumidero, Pinar del Rý´o, and kept in his

private collection (OA 2969). He also noted some other

appendicular elements of “Xenicibis sp.”, including the

distal end of a left tibiotarsus, a left tarsometatarsus,

and one phalanx, all uncataloged at the time but now

numbered OA 2970a, OA 2971, and OA 2972, respectively.

These bones were found in association with the

humerus, and the tarsometatarsus was described

briefly.

As part of my revisionary work on Arredondo’s paleontological

collection, I examined all of the above

material and found that it does not represent the genus

Xenicibis, nor any other ibis (Threskiornithidae).

Instead, these specimens agree in all their osteological

characters with Aramus guarauna, the Limpkin (Aramidae),

a gruiform structurally similar to primitive

cranes (see Olson 1985). Arredondo did not compare

his material with Aramus, and his identification of the

fossil specimens was based on comparisons with illustrations

of Xenicibis xympithecus (see Arredondo 1984).

The Limpkin is widely distributed in the Neotropics

and is fairly common in Cuba (Garrido and Garcý´a

Montan˜a, 1975). It occurs in other Greater Antillean

islands near bodies of water, rice fields, wooded floodplains

of rivers, and upland wet forest (Raffaele et al.,

1998:265).

The left humerus reported by Arredondo is inside

the range variation of a small series of skeletons of

Aramus guarauna from Cuba. It is partially covered by

travertine, showing wear on the pectoral crest, internal

tuberosity, and bicipital crest. The other referred specimens show some differences in color and degree

of mineralization in comparison with this last specimen.

The humerus of Xenicibis is characterized by a

slender twisted shaft, bicipital crest reduced, pectoral

crest reduced in area, thickened, and twisted; external

tuberosity reduced and displaced distally, with a very

deep and wide brachial depression (Olson and Steadman,

1979). None of these flightless characters occurs

in the Cuban humerus, which has a much shorter shaft

that is less curved latero-medially and not twisted and

flattened up to the mid point; the bicipital crest is well

developed and not reduced, and placed proximally;

the external tuberosity is more proximal and well defined,

not distal and reduced; the pectoral crest is large

and wide instead of short and thin.

None of the other bones show diagnostic characters

of the genus Xenicibis, such as very wide anterior intercondylar

fossa and reduced supratendinal bridge in

the tibiotarsus, or tarsometatarsus with two simple

calcaneal ridges well separated by a deep groove (Olson

and Steadman, 1977). In all respects these bones

agree with Aramus guarauna, particularly in having a

wide supratendinal bridge, a thin intercondylar sulcus

of the tibiotarsus, and a tarsometatarsus with closed

calcaneal ridges that form canals, among other characters.

However, these specimens represent the first

record of Aramus guarauna in Cuban Quaternary deposits.

The genus Xenicibis is known only in Jamaica, where

its flightlessness evolved. Water barriers that constantly

separated that island from Cuba throughout

geological history (see Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee,

1999) prevented the dispersal of this genus to Cuba.

Acknowledgements.—I thank Prof. Oscar Arredondo

for his assistance during the revision of his paleontological

collection. Gilberto Silva Taboada (Museo Nacional

de Historia Natural de Cuba) and Storrs L. Olson

(Smithsonian Institution) made valuable

comments on the first drafts of this manuscript.

www.uprm.edu/publications/cjs/Vol37a/37_109-110.pdf