|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 12, 2006 21:02:00 GMT

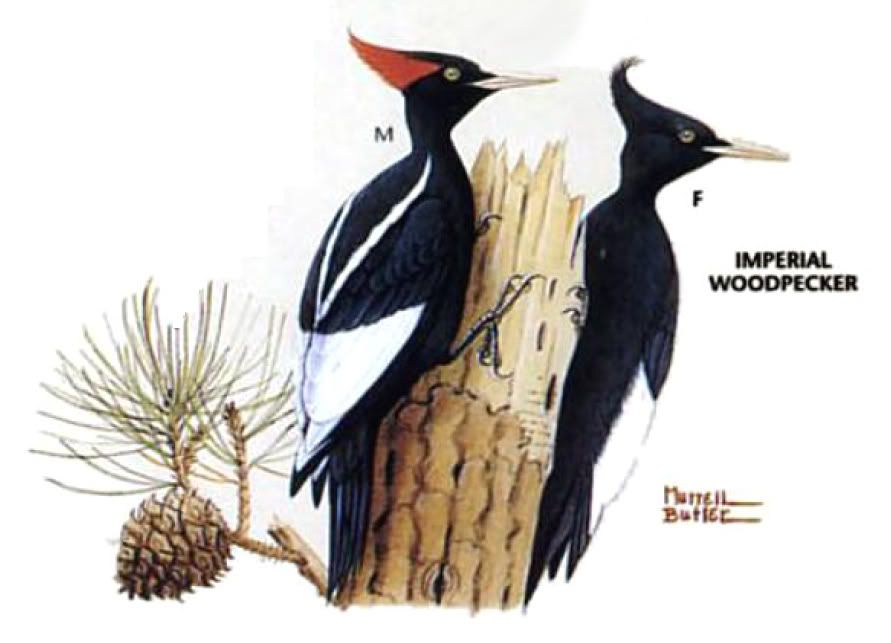

Imperial Woodpecker Campephilus imperialis Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct). Easily the largest woodpecker ever known (20% larger than the Ivory-billed Woodpecker C. principalis), the Imperial Woodpecker has not been conclusively identified since 1956. It is, or was, an inhabitant of old-growth pine forest in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico. Sadly, a great deal of natural habitat within this range was removed during the Second World War, and the remainder has been severely fragmented by logging. Given that Imperial Woodpecker was also a favourite quarry of rural hunters40,60, the outlook for this magnificent bird (Fig. 5) is dismal. Most recent analyses (e.g. Mendenhall49) have concluded that it has a far slimmer chance of survival than the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Nonetheless, the original range was fairly large, and reports of sightings surface occasionally and require followup. For example, a bird was reported in November 2005 in the Barrancas–Divisadero region of Barranca del Cobre, Chihuahua, Mexico, but subsequent searches did not find Imperial Woodpeckers, nor appropriate habitat or recent local knowledge of the species, within a 50 km radius of the locality (G. R. Homel in litt. 2005). Such leads should continue to be pursued until the chances of survival are deemed nil. If the species does survive it would be between 1,900 and 3,100 m above sea level, in extensive mature tracts of pines—if any still exist—in the Mexican states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Durango, Nayarit, Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacán. www.neomorphus.com/work/JPDF/lostandfound.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Bhagatí on May 9, 2007 23:17:25 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 17:19:48 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 17:21:32 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 17:23:23 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 17:25:32 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 17:27:57 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 18:41:19 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 18:42:03 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 18:47:34 GMT

Elusive imperial woodpecker has escaped extinction In 2002 we observed a very large male imperial woodpecker feeding within 30 feet for over three minutes. At the time, we were looking for orange-breasted falcons and unaware of the imperials status. Being primarily a raptor biologist, I knew the sighting was important, but kept it quiet until now when I became appalled at the controversy surrounding the ivory-billed woodpecker. I had seen similar apprehensible behavior with peregrine falcon biologists during it's recovery. Negativity was always hindering work which would later save the species. I directed several more trips to the location without a second sighting, but unlike the ivory-billed plight, the habitat is in excellent condition with thousands of acres of trees in an old growth forest condition. Therefore, I feel the time is right to bring this out mainly to help people understand we are extremely fortunate to get another chance at this, not only for the imperial, but the ivory-billed as well. Quite simply, for all the skeptics, I have no problem telling you, unless I actually saw the very last imperial woodpecker(from all of my experience with endanged raptors this would be extremely unlikely) everyone will have a chance to see the proof for the imperial as well as the ivory-billed in the near future. For my part, I created a life sized painting of the imperial and everyone interested in helping with any of the Campephilus research, I will be donating the profits to such efforts. The male imperial is incredibly large and the painting shows the bird just as I observed it landing. There is no mistaking this bird with any other at such close range as it literally matches a red tailed hawk or other large buteo in length. The closest sized woodpecker in the region is the pale-billed which is common in the area, but literally drawfed by the size of the imperial. Of course, this makes the Ron and Sorojam Makaus sighting extremely likely as that sighting is actually in a more historical range. Also, a female imperial, if you look at the museum specimens, equally drawfs any other woodpecker including the ivory-billed.(see about bar) Even if you are not interested in research, the prints are beautifully reproduced on both canvas(limited edition) or archival paper. I attempted to make this the definitive study of the imperial to date as I was fortunate as an artist to actually observe the bird very closely for several minutes. Also, for anyone wanting an actual life-size painting reproduced on canvas, that can be done by special arrangement. Greg Hayes D.V.M. Colorado State University; BS Zoology Claremont college. Prints 20"x20" archival paper $ 85.00 plus s/h 20"x20" limited signed edition canvas $ 265.00 plus s/h all prints are unframed unless otherwise specified (framing can be arranged) 40"x40" very limited signed edition life size on canvas $ 985.00 www.imperialwoodpecker.com/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 11, 2008 18:52:50 GMT

World’s Largest Woodpecker" By Vern and Lori Geiger March 2004 Guadalajara-Lakeside Volume 20, Number 7 When we think “woodpecker,” many think of a bird banging its bill against a tree or a telephone pole. Or perhaps we recall the good ole “Woody Woodpecker Cartoon.” However, few think of the King of Woodpeckers: The Imperial Woodpecker. What makes this bird so special? For starters, at 60 centimeters (23.6 inches) in length, it is the largest woodpecker in the world. The male displays a brilliant red, pointed crest on an otherwise black head. The body plumage of this magnificent bird is a stunning black and white. The female, while lacking the brilliant red crest, is equally stunning in her black and white plumage, having a long, curling black crest. Not only are they beautiful, but their physical make up is just as impressive. They have a strong ivory colored bill, a very thick skull, and between the bill and the skull is a pad of spongy connective tissue that acts as a cushion. They also have “yoked” feet, with two toes pointing forward, and two backward, with sharp, strong claws. Although the feet are adapted for clinging to a vertical surface, they are also used for grasping and perching. The tail is stiffened, with the shafts of the feathers terminating in hard spines, which the birds press against a vertical surface to help support, their weight. It also has another very special piece of equipment to help them, a long, elastic tongue that can easily get around curves. The tongue has a sticky glue-like substance on the end, to get the ants that are scurrying around in their tunnels. Unlike most other birds, woodpeckers like to eat ants. Once found throughout the huge Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico, including Jalisco, their numbers have been steadily declining, with no confirmed sightings in recent years. So, do not rush out with your binoculars in hopes to catch a glimpse of one. The imperial woodpecker will be listed in the 2004 IUCN Red List of endangered species under the new classification of “Critically Endangered Possibly Extinct.” (New tag assigned to some Critically Endangered species by Birdlife International to indicate those species which are likely to be extinct, but for which there is a small chance that they may still exist.) A joint expedition by Bird Life International and a local Mexican conservation organization, Prosima, spent 16 days in an isolated part of Durango state, where there was an unconfirmed sighting in a pristine canyon in 1996. The site researchers explored was close to an area where two years before, researchers had found some evidence of the species; unfortunately, they were unable to confirm any sightings. On July 11, 2003 Birdlife International researchers ex-pressed their fear that the stunning Imperial Woodpecker, may now be extinct after the expedition to the last area reporting sightings of the bird, failed to find evidence of a resident population. The bird’s decline is due to the loss of habitat requiring an extensive area (26 km2 per pair) of continuous open and untouched pine forest with dead trees for feeding and nesting. Although large areas of pine forests still remain in the Sierra Madre Occidental, they are being logged, the dead trees along with their associated insects removed. Hunting is also thought to have contributed to the bird’s downfall. Is there still a glimmer of hope? Could this bird still exist? Let’s hope so. For, the world will be a poorer place without this magnificent bird—the Imperial Woodpecker. www.chapala.com/chapala/ojo2004/woodpecker.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 28, 2009 18:25:47 GMT

My own photos from Natural History Museum of London - June 25   |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 28, 2009 18:26:43 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jun 29, 2009 21:35:30 GMT

Great to see a museum that appears to display a large portion of its collection, the same cant be said about the Museum of Natural History here in Stockholm, they seems to be more focused to build playing grounds for kids.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 30, 2009 5:00:22 GMT

It was nice to see a few more specimens.

Each one I go to something new is on show.

|

|

nicmuz

Junior Member

Posts: 11

|

Post by nicmuz on Sept 4, 2010 14:40:50 GMT

i went to my google earth and saw the durango's and others areas with historic breeding prescence of the Big Imperial... there're a few areas in very isolated gorges surrounded by scattered oak forest, and in these gorges are big pine-oak old growth pristine forests... but i have my doubts, its more likely to be IBWO alives in the few swamp and pine forests of USA and more possible Cuba, than IMWO in the very little remnant of the logged forests

|

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Sept 17, 2011 4:08:55 GMT

From ''A Filed Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Adjacent Areas'' |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 27, 2011 19:44:44 GMT

The only existing film footage of the Imperial Woodpecker is now availabe The largest woodpecker that ever lived and the closest relative of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker probably went extinct in Mexico in the late 20th century concludes a paper just published in the October 2011 issue of The Auk, the scientific journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union. It was thought that no photos or film of the two-foot-tall, flamboyantly crested bird existed, until a biologist from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology tracked down a 16-mm film shot in 1956 by a dentist from Pennsylvania. The footage captures the last ever confirmed sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker. The researchers not only restored the film to use it to describe the species’ behavior but also to study the habitat of the woodpecker by tracking down the exact filming location during a 2010 expedition to the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains, in Mexico. This ’lost species’ survey, was co-funded by The British Birdwatching Fair – Founding Global Sponsor of the BirdLife Preventing Extinctions Programme. Pronatura (BirdLife in Mexico) helped with the expedition logistics. “It is stunning to look back through time with this film and see the magnificent Imperial Woodpecker moving through its old-growth forest environment, and it is heartbreaking to know that both the bird and the forest are gone,” said Martjan Lammertink, lead author of the paper. In the color film, a female Imperial Woodpecker hitches up and forages on the trunks of large Durango pines. The bird’s extraordinary crest of black feathers curves up over her head, shaking as she hitches up the tree and chips at bark with her long, pale bill. As she launches into flight, the bird shows a long pointed tail, long wings, and a powerful, fast flight. The film was shot by William L. Rhein, a dentist and amateur ornithologist from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who went to Mexico in 1953, 1954, and 1956 specifically to film and record the sounds of the Imperial Woodpecker. He finally succeeded in filming the bird in 1956, shooting the footage hand-held from the back of a mule, while camping in a remote location in the Sierra Madre Occidental in Durango state. No sound recordings were obtained of the species by Rhein or any other recordist. Rhein died in 1999 at age 89. During the 2010 expedition local residents were interviewed about the Imperial Woodpecker and explored a few remaining old-growth forests in areas inaccessible to logging. The survey found no evidence that Imperial Woodpeckers are still alive. Only residents in their late 60s or older remembered it, and no one reported seeing any of the birds after the 1950s. “Even in the rare remnants of uncut forest, we found evidence of hunting and saw old-growth forests being cut and burned and planted with marijuana and opium poppies,” said Tim Gallagher, a member of the expedition. The entire range of the Imperial Woodpecker lay in the high country of the Sierra Madre Occidental—a rugged mountain range stretching some 900 miles south from the U.S.-Mexico border—and the Transvolcanic mountains of central Mexico. The species largely vanished in the late 1940s and 1950s as logging destroyed their old-growth pine forest habitat. Imperial Woodpeckers were also frequently shot for food, to use in folk remedies, or out of curiosity. One interviewee reported that logging interests in the 1950s actively encouraged the extermination of these birds, saying that they were destructive to valuable timber, and actually supplied poison to smear on the birds’ foraging trees. Similar poisoning campaigns had been waged against the Mexican wolves and grizzly bears in these mountains, and both of these subspecies are now gone. The article in the Auk—”Film documentation of the probably extinct Imperial Woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis)”—by Martjan Lammertink, Tim Gallagher, Ken Rosenberg, John Fitzpatrick, and Eric Liner of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and Jorge Rojas-Tomé of Organización Vida Silvestre and Patricia Escalante of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM)—analyzes the film and provides details about the 1950s expeditions of William L. Rhein and the 2010 Cornell Lab follow-up expedition. www.birdlife.org/community/2011/10/imperial-woodpecker-1956-film/Here are the clips www.birdlife.org/community/2011/10/imperial-woodpecker-video-clips/Here is the paper of the Imperial Woodpecker www.birds.cornell.edu/Netcommunity/bbimages/clo/images/wedo/Imperial_AukPaper_hi.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 27, 2011 19:57:09 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 27, 2011 19:58:49 GMT

Conservation Science Program Imperial Woodpecker Film: Bonus Materials In the mid-1990s, researcher Martjan Lammertink found letters in Cornell University's Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Carl A. Kroch Library, written by William L. Rhein and Frederick H. Hilton to Cornell researcher James Tanner in 1962. The letters mentioned the existence of an Imperial Woodpecker film. Lammertink tracked down Rhein on November 17, 1997, and interviewed him, then age 88, at his residence in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. With Mr. and Mrs. Rhein, Lammertink viewed the old film which Rhein shot from the back of a mule in 1956 during a Durango, Mexico expedition. Rhein's commentary from that 1997 viewing is combined with the old film footage (below) of this film--the only photographic evidence of the Imperial Woodpecker ever found. Note that Rhein refers to the woodpecker as an "ivory-bill." These birds were often referred to as Imperial "Ivory-billed" Woodpeckers at that time. William Rhein passed away in 1999, and in 2005 his nephew, R. Thorpe, donated the film to the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. In 2009, expedition member Richard Heintzelman provided landscape still slides he took in 1956. In 2010, Lammertink and Gallagher went to the Sierra Madre Occidental and used the 1956 slides to identify the Imperial Woodpecker film spot www.birds.cornell.edu/Page.aspx?pid=2316 |

|