|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 20, 2005 7:28:26 GMT

thanks for source

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 18, 2007 7:11:22 GMT

barbary and cape lion size extinctanimals.proboards22.com/index.cgi?board=carnivora&action=display&thread=1182442008This thread has now been deleted and all info has been copied and pasted here. I study many book, articles and sites about a size this lions subspecies. I think, that both are huge size and are bigger than others, extant living lions. I think, that notes given by Gerard to the barbary lions- 275-300 kg could be right, Of course, 17 feet long lions are huge mistake, but the weight could be a truly. I have seen a mounted barbary lion, which was truly enormous (pic in the gallery), but I know also stuffed cape lions which were not unusually large. The "typical" traits like size, colour and mane of cape and barbary lions were in fact much lesser typical than often said, and they showed also a very wide variety and also untypical specimens. According to Yamaguchi and Haddane (2002) the Barbary Lion is the largest of the lion subspecies with males weighing between 230 to 270 kg and females 140 to 160 kg. Although, due to a small sample size available for study, we have to wait until more specimens may become available to be sure about this lion's size. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 26, 2007 15:29:58 GMT

Inventory number: 52 Panthera leo melanochaita - Cape Lion [sensu card index] Panthera leo capensis [sensu inventory book] Panthera leo vernayi - Kalahari Lion [sensu HECK (1966)] adult origin: 1902, Kalahari desert via Carl Berger skull further information www.nws-wiesbaden.de/coll044.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 26, 2007 15:31:22 GMT

In addition: A skull of a lion from the Kalahari desert with following informationen: * according to the inventory book (prob. 1903): Panthera leo capensis, Kalahari desert, SW-Africa, 1902, C. Berger, missionary [inventory number 52] * according to the index card (prob. 1970): Panthera leo melanochaita, Kalahari desert, SW-Africa, missionary Carl Berger, 1902 [inventory number 52] According to the paper of (1966), it is probably a skull of Panthera leo vernayi. www.nws-wiesbaden.de/coll011.html#desert |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 26, 2007 15:34:35 GMT

Inventory number: 358 Panthera leo melanochaita - Cape Lion male, adult origin: 1864, Cap, South Africa, via Curhaus Administration mount  Inventory number: 359 Panthera leo melanochaita - Cape Lion female, adult origin: 1864, Cap, South Africa, via Curhaus Administration mount www.nws-wiesbaden.de/coll044.html |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 10, 2007 21:15:42 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 11, 2007 11:17:20 GMT

From Brehms Thierleben Vol.1 2nd ed. 1876 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 18:10:56 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 18:12:35 GMT

The Cape Lion Panthera leo melanochaitus is an extinct in the wild subspecies of lion. Cape "black-maned" Lions ranged along the Cape of Africa on the southern tip of the continent. The Cape Lion was not the only subspecies living in South Africa, and its exact range is unclear. Its stronghold was Cape Province, in the area around Cape Town. The last Cape Lion seen in the province was killed in 1858. As with the Barbary lion, several people and institutions claim to have Cape lions. In 2000, possible specimens were found in captivity in Russia and brought to South Africa for breeding. [1] There is much confusion between Cape lions and other dark-coloured long-maned captive lions. Lions in captivity today have been bred and cross-bred from lions captured in Africa long ago, with examples from all of these 'subspecies'. Mixed together, hybridized, most of today's captive lions have a 'soup' of genes from many different lions.[2] 1927 Painting 1927 Painting Early authors justified ‘‘distinct’’ subspecific status of the Cape lion on believe that the seemingly fixed external morphology of the Cape lions (male’s huge mane extending behind shoulders and covering belly, and the distinctive black tips to the lion's ears). However, nowadays it is known that various extrinsic factors, including the ambient temperature, influence the colour and size of a lion’s mane.[3] Results of mitochondrial DNA research published in 2006 do not support the ‘‘distinctness’’ of the Cape lion. It now seems probable that the Cape lion was only the southernmost population of the extant southern African lion. [4] [edit] References 1. ^ BBC News. 5 November, 2000: 'Extinct' lions (Cape lion) surface in Siberia. Downloaded on 2 July 2006. 2. ^ Maas, P.H.J. 2006. Cape lion - Panthera leo melanochaitus. The Extinction Website. Downloaded on 2 July 2006. 3. ^ West P.M., Packer C. (2002) Sexual selection, temperature, and the lion’s mane. Science, 297, 1339–1343. 4. ^ Barnett, R., N. Yamaguchi, I. Barnes & A. Cooper. 2006. Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation. Conservation Genetics. Online pdf en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cape_Lion |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 18:17:56 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 18:25:15 GMT

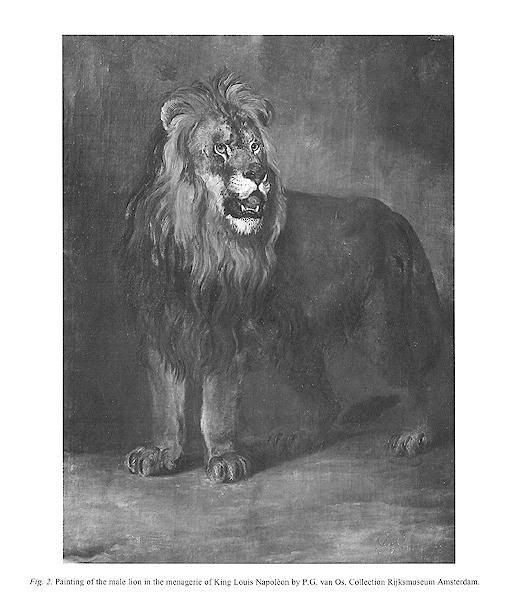

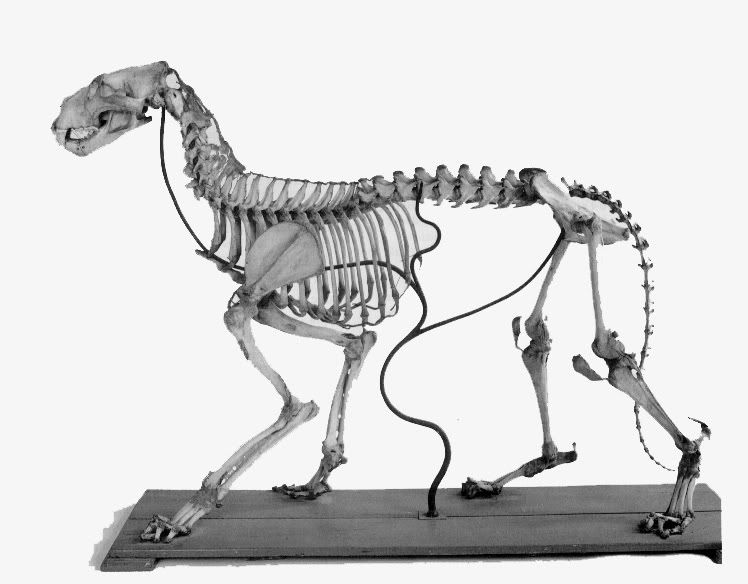

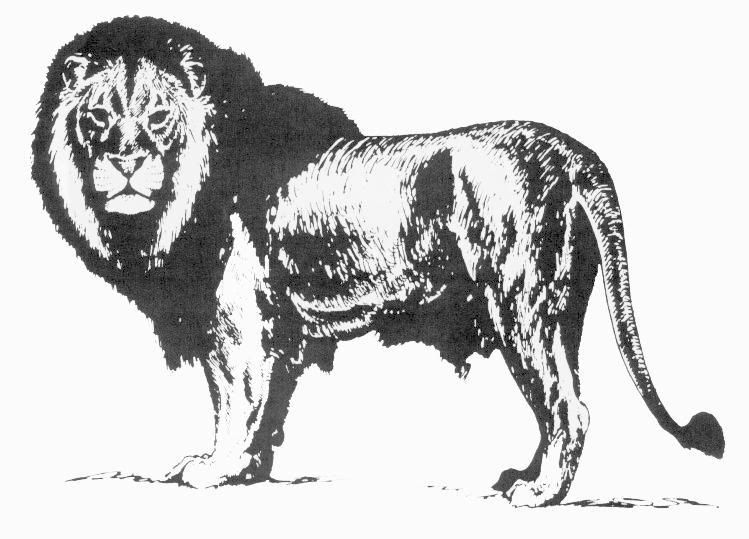

Short notes and reviews On a mounted skeleton of apparently the extinct Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) P.J.H. van Bree Zoological Museum, University of Amsterdam, . P.O. Box 94766, 1090 GT Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Keywords: Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaita, , skeleton study, Vrolik’s museum Recently, the skeleton of apparently a Cape Lion was discovered in the Zoological Museum of the University of Amsterdam. The history of the specimen as far as known is summarized and its attribution to Panthera leo melanochaita is elucidated with some measurements taken from the skeleton and the study of fur colours and manes’ development on an oil painting of the same animal in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Both the animal and the painting once belonged to King Louis Napoléon Bonaparte of Holland. For quite some time there has been a mounted skeleton of a large lion (reg. nr ZMA 710) kept in the collections of the Zoological Museum in Amsterdam. Recently the skeleton came under scrutiny and the whole history of the object became known (van Bree & Welman, 1996). When alive, the lion formed part of a travelling animal show under the management of Antoine Alpy that toured the Netherlands during the beginning of the 19th century. In July 1808 King Louis Napoléon, the Netherlands being at that time occupied by the French, ordered that the collection of animals of Alpy should be bought to form the nucleus of a menagerie he wanted to have, just like the one in Paris in the Jardin des Plantes (formerly named Jardin du Roi). The animals, among them two lionesses and the lion under discussion, were brought to Palace Soestdijk at Baarn and after a few months removed to an estate near the town of Haarlem. It was also intended to establish a Royal Botanical Garden there and for that purpose exotic plants were purchased (see Evers 1941). The menagerie of the king was enlarged by buying some other collections. Just as the animals were properly installed at Haarlem, the rather fickle King Louis Napoléon ordered on 22 May 1809 the removal of all the animals and plants to Amsterdam. There the animals were housed in the greenhouse of the town’s botanical garden; the plants were put temporarily in the garden of a large house, the “Trippenhuis”, which was the seat of what later would become the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences. In that same building was also housed the national art collection, which would become the state art museum, the Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam. During winter 1809/1810 the animals went to empty barracks, so that the (sub)tropical plants could be placed in the greenhouse. On 10 June 1810, the king decided to dissolve the menagerie; on 2 July of the same year, under pressure of his brother emperor Napoléon Bonaparte, he abdicated and left the Netherlands. Finally on 30 September 1810 the remainder of King Louis Napoléon’s menagerie was sent to Paris. The lions were already dead by then. During the time the menagerie was in Amsterdam, Gerardus Vrolik (1775-1859), professor of medicine and botany at the Athenaeum Illustre, was a member of the board of the Hortus Botanicus, the town’s botanical garden and at the same time he was co-director of the menagerie. He started a museum very early in life, consisting of prepared human parts and zoological objects. The lion, which is the subject of this paper, died between May and August 1809 and professor Vrolik obtained the body of the animal for his museum. The museum “Museum Vrolikianum” was enlarged considerably by his son, professor Willem Vrolik and became known as the best private museum in Europe at the time (Dusseau 1865). Willem Vrolik died in 1863 and it looked like the museum would have to be dissolved. However, funds were raised and in 1865 the collection was purchased from the heirs. All the medical objects were given to the town of Amsterdam for its Atheneum Illustre (the precursor of the Amsterdam University) and the zoological part of the collection came into possession of the Zoological Society “Natura Artis Magistra”, founded in 1838. This society administered a zoo, which still exists, a zoological museum, an ethnographical museum and a library. When in 1892 the Amsterdam University started its own zoological museum, its staff also curated the society’s collection untill 1939. In that year the society’s museum collections became officially part of the university’s Zoological Museum (Smit 1980). In 1808, the Dutch painter P.G. van Os (1776 - 1839) submitted a painting of the male lion from the menagerie of the king to the exposition of modern art in the Netherlands. That exposition was an initiative of King Louis Napoléon. After the exposition the artist donated the painting to the king. It was incorporated in the state art collection, which after being housed at several places, is now in the Rijksmuseum (of art) in Amsterdam (see Fig. 2). Only recently we have become aware that the skeleton and the painting pertain to the same animal.  Fig. 2. Painting of the male lion in the menagerie of King Louis Napoléon by P.G. van Os. Collection Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. After examining at the painting of the lion, with its long dark-coloured chest manes and its black belly manes, suspicion arose that the animal could be a Cape Lion. Therefore the skeleton and in particular the skull were studied in detail. Thanks to the studies of the late Czechoslovakian zoologist Vratislav Mazak in the years 1960-1970, we know much about Cape Lions. He studied almost all the extant specimens in museums and furnished a good description of this extinct subspecies, which lived in the vast plains of the South African interior that lie west of the Great Eastern Escarpment (Mazak 1975). The subspecies was most probably exterminated around 1850. The skull of the Amsterdam mounted skeleton is difficult to study. It is attached to the spinal column by a dried tendon (see Fig. 1) and skull and vertebrae are connected by dried tissue. Also the lower jaw is attached to the skull by dried tissue. Therefore accurate length measurements cannot be taken, but nevertheless some other measurements could be ascertained. To wit: rostral breadth 107 mm, rostral depth 88 mm, greatest length of nasals 96 mm, prosthion-meatus acusticus externus 268 mm, interorbital breadth 73 mm, postorbital breadth 58 mm, bizygomatic breadth 244 mm, mastoid breadth 142 mm greatest height of mandible 112 mm (for the definitions of these measurements see Mazak 1975: 40).  Fig. 1. Mounted skeleton of apparantly the extinct Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H.Smith, 1842) in the collection of the Zoological Museum Amsterdam. Photograph by L.A. van der Laan. Although a number of important measurements are missing, those that could be taken point to a skull of a Cape Lion. In spite of the fact that the skeleton (see Fig. 1) is mounted in an unnatural way (it stands too high on its legs), it is clear that the animal was a large one. Measured with a tape, the distance from the anterior border of the nasals over the skull, over the tendon that connects the skull with the neural spines of the vertebrae till the last caudal vertebra, one arrives at a length of 256 cm. Taking into account the very dark coloured chest and shoulder manes and the black belly manes, the size of the animal, and the dimensions of the skull, one comes to the conclusion that the specimen is most probably a Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaita . In addition circumstantial evidence should be taken into account. First, till the middle of the 19th century the only lions arriving in Europe either came from North Africa or from the Cape. Only after that time did lions also come from East Africa and India. In view of the painting it is clear that the lion under discussion is not a Barbary Lion, Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758). Secondly the Cape was till 1795 a Dutch colony and in the 18th century living animals from South Africa regularly arrived in the Netherlands. For instance in the private Zoo of Stadtholder Prince William V many Cape animals could be seen. Some of them were described by the well-known zoologist Simon Peter Pallas when he visited the Hague between 1763 and 1767 (e.g., Wart Hog and Rock Dassie). As pointed out by Mazak & Husson (1960), the famous Dutch artist Rembrandt (1606-1669), who never left his country, made a drawing of a reposing lion, which looks like a Cape Lion (Fig. 3).  Fig. 3. How the Cape Lion probably looked in life. After Mazak, 1968. Thus taking everything into account, in spite the fact that of the early history of the lion before it came in the menagerie of King Louis Napoléon is unknown, it is highly probable that it was indeed a Cape Lion. The mounted skeleton is the second Cape Lion in the collection of the Amsterdam Zoological Museum. The first one, a mounted skin has been described and pictured by Mazak in 1975. Bree PJH van, Welman W. 1996. Een leeuw van Lodewijk Napoleon. Amstelodanum 83 (6): 179-184. Dusseau JL. 1865. Catalogue de la collection d’anatomie humaine, comparée et pathologique de M.M. Ger. et W. Vrolik: 1-XVI, 1-464 (de Roever Kröber - Amsterdam). Evers GA. 1941. Utrecht als koninklijke residentie - het verblijf van Lodewijk Napoleon te Utrecht 1807-1808. Utrecht: A.W. Bruna & Zoon, 1-208 Mazak V. 1964. Preliminary list of the specimens of Panthera leo melanochaitus (Ch.H. Smith, 1842), preserved in the museums of the whole world in 1963. Z. Säugetierk. 29 (1): 52-58. Mazak V. 1968. Der Löwe. Das Pelzgewerbe 19 (3): 3-27. Mazak V. 1975. Notes on the black-maned lion of the Cape, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) and a revised list of the preserved specimens. Verhand. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch. (Natuurk.) (2) 64: 1-44, XI pls. Mazak V, Husson AM. 1960. Einige Bemerkungen über den Kaplöwen, Panthera leo melanochaitis (Ch. H. Smith, 1842). Zoöl. Mededel. (Leiden), 37 (7): 101-111. Smit P. 1988. Artis - een Amsterdamse tuin. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1-10, 1-392 dpc.uba.uva.nl/ctz/vol68/nr01/art04 |

|

|

|

Post by kabilann on Mar 17, 2008 15:05:05 GMT

hey how about the lion that attack many people in tsava maybe they are cape lion?? pls answer my question??

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Mar 17, 2008 16:07:06 GMT

No at all. Tsavo and the Cape region are complete different regions and therefore there are different subspecies of the lion. hey how about the lion that attack many people in tsava maybe they are cape lion?? pls answer my question?? |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Mar 17, 2008 16:45:56 GMT

THE CAPE LION The "black-maned" lion of the Cape was once distributed in the southwestern part of South Africa (Mazák 1975). Unlike the Barbary lion which would have been isolated from other African lions by the Sahara, the Cape lion was in close geographical proximity to other lion populations in southern Africa. Considering this, the Cape lion may have maintained genetic exchanges with the widely distributed southern African lions, P. l. krugeri. Lions in the Kruger- Mozambique region came down to the southern most parts of South Africa through the narrow corridor between the Great Escarpment and the Indian Ocean (Mazák 1975). Probably, many "Cape lions" recorded in the eastern side of the Great Escarpment in the Cape Province (Skead1987) may have been the current Kruger-Mozambique lion. Interestingly, however, Mazák (1975) also suggested the Cape lion may not have had a regular population mixture with the Kruger- Mozambique lion because of a geological barrier, mountainous terrain of the eastern side of South Africa (the Great Escarpment). Separated by the Great Escarpment, the Cape lion distributed south-west and the Kruger- Mozambique lion north-east. There may be another circumstantial evidence to suggest that lion populations in southern Africa may not have been mixed constantly in spite of their relative geographical proximity to each other. More than 80% of lions in the Kruger National Park are feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) positive, but, there is no FIV positive lion in the Etosha National Park (Spencer etal. 1992, Brown et al. 1994). Assuming the Kruger lion has been associated with FIV for a considerable period (Brown et al. 1994) there may not have been a large lion population mixture between the regions represented by the two parks. Although it is not known how hard the River Orange and its tributaries were for lions to cross, the Cape lion may have closer genetic association with lions in Kalahari region. If the ancient DNA technique can extract Cape lion's DNA, comparing it to those of Kruger and Kalahari lions, this question would be answered. Then, if some populations of the existing southern African lion appears to be acceptably close to the extinct Cape lion, the resurrection of the black-maned lion lost in the Cape Province may become a feasible conservation project. www.tigertouch.org/library/barbarycape.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jun 23, 2008 14:36:49 GMT

On the distinctiveness of the Cape lion (Panthera leo melanochaita Smith, 1842), and a possible new specimen from the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen

The Cape lion was a population of lions that probably inhabited the western part of the Cape Province of South Africa until their extermination by man in the mid-19th century. Only a few skeletal remains are known, making every specimen valuable. In this paper, I report on a possible new male specimen CN1570 from the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen. A multivariate discriminant analysis on 27 craniodental variables provided clear separation between four of the five lion subspecies (Panthera leo krugeri, nubica, persica, senegalensis) that were included, whereas P. l. bleyenberghi showed some overlap with P. l. senegalensis and P. l. krugeri. The only two undisputed Cape lion males grouped separately from all other lions. CN1570 also grouped separately from other lions, and towards the two Cape lions. The external morphology of the Cape lion is often cited as having been different from other sub-Saharan lions, but phenotypic plasticity argues for caution in placing emphasis on mane morphology as a distinguishing character among lion subspecies. Skull morphology, however, appears to clearly distinguish male Cape lions from other African lions.

The Cape lion (Panthera leo melanochaita Smith, 1842) is traditionally regarded as having been a distinct subspecies of the large, darkly coloured lion that was exterminated by man in the middle of the 19th century

(Hemmer 1974; Mazak 1975). The physical appearances of preserved Cape lion specimens differ from those of typical East African lions, which are lighter in colour, have lighter manes and usually have little or no bellymane. In contrast, the Cape lion had a capacious, dark´mane with a sharply defined border, to the tawny hairs fringing the face, and a long belly mane, where the hairs were longest anterior to the hind limbs (e.g., Stevenson-Hamilton 1954; Mazak and Husson 1960; Mazak 1964a, b, 1975). The exact implication of the commonly referred ‘‘bulldog’’ appearance of the head is elusive, but probably relates to the deep, heavy rostrum (Mazak 1975; below). Only two undisputed male skulls are known (Mazak 1975), and one female skull (Lundholm 1952), and claims of additional specimens (Hemmer 1966; Meester 1971; Van Bree 1998) are tentative and have subsequently been called into question (Mazak 1975; Barnett et al. 2006). Unusually, both of the males have a fully developed P2, although this is not present in the lower jaw of the Cape lioness (Lundholm 1952). This trait is entirely absent from other populations of lions (e.g., Todd 1965; Mazak 1975; Smuts et al. 1980, pers. obs.), and other extant felids, but is present in more archaic stemfelids such as the Miocene basal felid Pseudaelurus (Rothwell 2001), or the Late Miocene basal machairodontine sabertooth Paramachairodus. Its presence in the Cape lion males is best regarded as an atavistic trait, whose function, if any, remains

obscure. The geographic distribution of the Cape lion is unknown, and previous suggestions that it was present throughout the Cape Province, extending up to Natal (e.g. Mazak 1964a), have subsequently been questioned, and available evidence tentatively suggests that it was present in the interior of the western part of the Cape province (Mazak 1975). The eastern coastal regions, which are separated from the plains north and west of Cape Town by a mountain range known as the Eastern

Escarpment, could have been inhabited by Kruger lions (Panthera leo krugeri) instead (Mazak 1975). The exact´time of extinction of the Cape lion remains obscure, but it would appear that they were getting rare by the 1850s, and probably disappeared sometime in the 1860s (Mazak 1975). Thus, very little is known about this lion form, and to date it is not even known if, indeed, it may be considered to have been a distinct subspecies

(e.g., Barnett et al. 2006). In this paper, I report on a possible additional male specimen of the Cape lion in the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen, and address the question of whether or not this lion population may be considered to have been distinct from other African lions, most notably the

Kruger lion, which is also present in South Africa, although its present range is now confined to the northwestern part (Sunquist and Sunquist 2002; Hunter and Hinde 2005).

Material and methods

The lion specimen presently catalogued as CN1570 was number 289 of a shipment consisting of two large crates of mammal skulls, skeletons and skins, bird skins and bird eggs, and some reptiles in spirits, which arrived at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen on April 26th 1864. The shipment was sent from the South African Museum in Cape Town by a Mr. Layard, as payment for an equivalent shipment of Nordic animals a number of years previously. Originally, it was due to have been shipped off in 1859 or 1860, but was delayed owing to a trip to Denmark by Mr. Layard. The exact time and location where the lion was shot are unknown, but according to museum annals much of the material was old and in rather poor condition. It appears likely, however, that the lion originated from the vicinity of Cape Town, where lions could still be found in the 1840–1850s. The museum annals read: "289 Felis leo, unfortunately so badly damaged (in part, by

insects) that it probably cannot be stuffed’’. The specimen originally consisted of a skin in poor condition and parts of the skeleton. In 1911, the skull (Fig. 1) and all four limbs (Fig. 2) were removed from the skin, which was subsequently discarded. Presently, the specimen consists of a skull in good condition, although the dentition is damaged, the right humerus, both radii, ulnae, femora and tibiae, and the distal two-thirds of the right fibula, all in good condition. Mani and pedes are present in their

entity, and the right manus is articulated while the left one is loose, and for the pes it is the reverse (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the left radius (Fig. 2C, D) is pachyosteotic around the middle, indicating a fracture, which, however, had healed prior to the lion’s death. CN1570 is a fair-sized male lion (Table 1), and the fully closed, and in many instances, obliterated sutures and rugged appearance of the limb bones indicate an older animal.

Some, but not all of the damage to the dentition is postmortem,

and all premolars show signs of heavy wear, corroborating the age of the animal (Smuts et al. 1980). The skull has a well-developed sagittal crest, in accord with the two male Cape lion skulls from the Natural History Museum in London, although this is frequently, but not universally

observed among large male lions. Previously, Cape lions have been said to be characteristic in having a deep muzzle and a short postorbital region of the

skull (Lundholm 1952; Mazak and Husson 1960; Mazak 1975), the latter implying that the sagittal region overhangs the occipital condyles by a modest amount only. Thus, the occipital region is less posteriorly inclined than in most other lions. Mazak (1975) found that a high condylobasal/total skull length ratio distinguishes the Cape lion from another South African lion, the Kruger lion, but that some East and North

African lions and Asian lions also have high ratios. CN1570 has a steeply inclined occipital region and a resulting condylobasal/total skull length ratio of 95.5%, higher than the Murraysburg female (94.8%; Lundholm 1952), and markedly higher than the male Cape lion BM36.5.26.6 (90.9)

and other lions (86.3–91.6; Mazak 1975). Previous osteological comparisons of the Cape lion to other lions (e.g., Mazak 1975; Van Bree 1998), and attempts to distinguish the purported subspecies of lion (e.g. Hemmer

1974) have focused on singular characters. To address the morphological distinction and validity of several of the purported lion subspecies and a possible reference of CN1570 to the Cape lion, 58 lions were digitally photographed in direct lateral, dorsal and ventral views with a millimetre

scale ruler positioned directly in the vertical plane of the long axis of the skull, and owing to lions being sexually dimorphic, only males were included. Apart from CN1570, the database consisted of the two male Cape lions BM36.5.26.6 and BM18.5.23.2, nine specimens of the Southwest African lion (Panthera leo bleyenberghi), eight specimens of the Southeast African or Kruger lion (P.l. krugeri), 24 specimens of the East African lion (Panthera leo nubica), five specimens of the Asiatic or Indian lion (Panthera leo persica), and nine specimens of the West African lion (Panthera leo senegalensis). The specimens are housed in the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen (CN), the Natural History Museum, London (BM), the Department of Zoology at the Museum fu¨ r Naturkunde, Berlin (ZMB), and

the Museum national d0Histoire Naturelle, Paris (MNHN). In all, 27 variables were measured on the included lions (Fig. 3), and owing to BM18.5.23.2 having had the posterior part of the skull cut off, overall skull length (variable 1) was from the jaw cotyle to the anterior tip of the premaxilla. The variables were logarithmically (log10) transformed, and were´analysed by means of a step-wise discriminant function analysis (DA). DA is effective in evaluating separation among groups, emphasizing variation among groups relative to within groups, by identifying canonical axes of the form SliXi, which are linear functions of the included variables, where li represents coefficients and Xi represents variables (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). The multiple regression derived from DA yields

the best least squares predictor of group assignment, and thus facilitates post hoc assignments of individual specimens to the formulated groups.

Results

The discriminant analysis showed clear separation of the included subspecies of lions (Fig. 4), and the U-statistic (Wilks’ l ¼ 0.0004) indicated that the group means are significantly different (po0.001). All but two specimens of the Southwest African lion (P. l. bleyenberghi) were identified with 100% accuracy in the subsequent classification analysis (Table 2). The fact that the two were misidentified as neighbouring lion

subspecies, P. l. krugeri and P. l. senegalensis, respectively, raises doubts about the subspecific status of P. l. bleyenberghi. The two Cape lions were clearly distinct from all other lions in a plot of the two first canonical

variables (Fig. 4), and the F-matrix also indicated that they were distinctly different from the two other South African lions, P. l. bleyenberghi and P. l. krugeri, as well as all other lions. The canonical variable plot and the Fmatrix values indicate that the Asiatic lion is the most aberrant, in accordance with it traditionally being considered a more primitive type of lion along with´the Barbary lion and Cape lion (Hemmer 1974), which has recently been corroborated by genetic analyses

(Burger et al. 2004; Burger and Hemmer 2006). CN1570 groups distinctly away from other lions, and tends towards the Cape lions.

Discussion

The clear separation based on skull characteristics in

the discriminant analysis suggests that the five included

traditionally proposed subspecies of lion are in fact

morphologically distinct, with the possible exception of

the Southwest African lion (P. l. bleyenberghi). The two

Cape lions are clearly different from other, sub-Saharan

lions and may, accordingly, also be assigned subspecies

status, as traditionally advocated. The specimen

CN1570 appears to show closer affinity to them than other lion subspecies. Although one cannot rule out that

it might be a morphologically aberrant East African lion

(P. l. nubica), its canonical scores and thus, overall skull

morphology, probable place and time of origin and

vertical occiput all argue against it.

An evolutionary geographic east–west dichotomy

appears to be present in many large, African mammals

(e.g., Georgiades et al. 1994; Arctander et al. 1999; Brown

and Houlden 2000; Van Hooft et al. 2002), indicating

that this could be present in lions also, as corroborated by

this study. The present study demonstrated morphological

divergence among the traditionally recognized African

lion subspecies, corroborating the results of genetic

variability in African lions by Dubach et al. (2005), in

which they found that there were distinct differences

between Southwest African, Southeast African, and

East African lions (equivalent to P. l. bleyenberghi,

P. l . krugeri, and P. l. nubica, respectively). However,

these authors also found differences within Kenyan lions,

which supposedly are all P. l. nubica. They considered the

four lion populations to be evolutionarily significant units

(ESUs), but argued that the amount of genetic variation

was too modest to warrant subspecific status. A similar

conclusion may be argued on the basis of the current

study on skull morphology. By this token, the Cape lion

was not a distinct subspecies either, although undoubtedly

an ESU, and thus worth protecting to preserve

biodiversity. However, such debates on taxonomy are

rarely solvable by unbiased methods. Subspecies or not,

the Cape lion was distinct from other African lions south

of the Sahara.

Van Bree (1998) referred a mounted skeleton from

Amsterdam to the Cape lion, although its origins were

unknown. Unfortunately, his descriptions are rather brief and no analyses were presented, but the specimen

does have a high rostrum compared with the length of

the nasals (as measured in Mazak 1975). Recently,

however, doubts have been raised as to the identity of

this specimen, which appears to have genetic characters

that are indicative of Asiatic lions instead (Barnett et al.

2006). A key feature in the subspecific proposition of the

Amsterdam specimen was the appearance of the mane,

as seen in a painting (Van Bree 1998), but the Barbary

lion (Panthera leo leo) also has a large, heavy mane and

a well-developed belly mane (e.g., Mazak 1964b, 1970;

Hemmer 1974). Additionally, since the Barbary lion has recently been shown to be related to the Asiatic lion

(Burger et al. 2004; Burger and Hemmer 2006), this

raises further doubts about the Amsterdam specimen. If

this animal is, in fact, a Barbary lion, then the limb

bones figured in this paper are the only postcranial

remains known from a probable Cape lion.

Traditionally, mane appearance has been used in lion

taxonomy (e.g., Fitzinger 1868; Weigel 1961), but the

natural variability in mane morphology among different

populations and/or subspecies (Hemmer 1974) and even

within the same areas (Guggisberg 1963) renders this

untenable, as also concluded by Hemmer (1974). The

Cape lion was supposedly distinct from other lion

subspecies because of its heavy, dark mane with sharply

contrasting tawny hairs fringing the face, a well developed belly mane with the hairs being longer

posteriorly than in the chest region, and in being a dark

ground colour (Mazak and Husson 1960; Mazak 1975).

However, mane size and colour is dependent on age

(e.g., Mazak 1964b; Hemmer 1974), climate (Hemmer

1974; Mazak 1970, 1975; Kays and Patterson 2002;

West and Packer 2002) and age-specific increases in

serum testosterone (West and Packer 2002). Mane

darkness increases with age and the age-specific increase

in serum testosterone, and increased ambient temperature

has a negative effect on mane darkness (West and

Packer 2002). The dark, heavily maned Barbary lion

also lived in a more temperate climate (e.g., Hemmer

1974; Mazak 1970, 1975), and manes frequently become

darker and heavier when transferring lions from

tropical climates to European or North American zoos

(e.g., Hollister 1917; Pocock 1930; Adamson 1961). The

importance of testosterone is amply demonstrated by

the frequent mane loss in castrated lions (e.g., Puschmann

1964; Vo¨ hringer 1966), and in particularly hot

climates, the mane may be almost absent (Kays and

Patterson 2002).

Dark-maned lions always have tawny hairs fringing

the face (e.g., Pocock 1930; Hemmer 1974), and East

African lions occasionally have dark, heavy manes with

tawny facial hair, although they most frequently lack

belly manes (Hemmer 1974). Even though wild-living

Asian lions have, on average, predominantly tawny and

shorter manes than African lions (Pocock 1930;

Hemmer 1974; Divyabhanusinh 2005), captive specimens

in cold climates can develop capacious manes

which are entirely black with a sharply defined tawny

hair fringe around the face, and a large belly-mane

(Divyabhanusinh 2005: p. 206; see also Wynter-Blyth

1949), thus superficially appearing very similar to

Cape lions. Accordingly, individual variation, climatic

influence, and phenotypic plasticity in mane size and

colour caution in placing emphasis on the external

appearance of the Cape lion, unusual as it may appear.

It also implies that superficial phenotypic characters

are dubious in claiming survival of pure-bred Cape

lions (Irwin 2001), which supposedly have lived in

obscurity for almost a century and a half after its

extinction in the wild. Lion subspecies are differentiated

by skull morphology rather than by external

appearance.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to curators Mogens Andersen at the

Zoological Museum in Copenhagen, Daphne Hills at

the Natural History Museum in London, Irene Mann

and Hendrik Turni at the Museum fu¨ r Naturkunde in

Berlin, and Jose´ phine Lesur-Gebremariam and Francois

Renault at the Museum national d’Histoire Naturelle in

Paris for assistance and hospitability. Two anonymous

reviewers provided many valuable suggestions to a

previous version of this paper.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 24, 2008 9:11:49 GMT

Hi sebbe is this another pdf file you have personally or is it on the web?

Looks interesting?

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jun 25, 2008 10:38:35 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 25, 2008 19:44:34 GMT

Thanks sebbe for info

|

|

|

|

Post by Bhagatí on Jul 22, 2008 19:19:08 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 24, 2008 7:01:36 GMT

|

|