Endangered Species Act 5-Year Review

Caribbean Monk Seal

(Monachus tropicalis)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

National Marine Fisheries Service

March 2008

5-YEAR REVIEW

Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION...................................................................................... 3

2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS................................................................................................... 5

3.0 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... 15

4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIONS.............................................. 15

5.0 REFERENCES............................................................................................................ 16

2

5-YEAR REVIEW

Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis)

1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION

1.1 Reviewers

Lead Regional Office

Kyle Baker, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries

Service, Southeast Regional Office, St. Petersburg, Florida (727) 824-5312

Cooperating Science Centers:

Jason Baker, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries

Service, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Larry Hansen, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries

Service, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Beaufort Laboratory, Beaufort, North Carolina

Gordon T. Waring, Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Woods Hole Laboratory, Woods Hole,

Massachusetts

Document Peer Reviewed By

Dr. Ian Boyd, University of St. Andrews, Sea Mammal Research Unit, St. Andrews, Scotland

William Johnson, Editor, The Monachus Guardian, Bern, Switzerland.

David Laist, Marine Mammal Commission, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

1.2 Method used to complete the review: This review was prepared pursuant to section

4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and in accordance with sections 4(a) and (b) of the

ESA following guidance provided in the joint NMFS and U.S. Fish and Wildlife 5-Year Review

Guidance and template (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/laws/guidance_5_year_review.pdf).

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA) initiated a 5-year review of the Caribbean monk seal (Monachus

tropicalis) in November 2006. NMFS convened a four-member status review team to compile

and review information to assess the status of the Caribbean monk seal. NMFS solicited

information from the public through Federal Register notice (71 FR 39327; November 29, 2006),

as well as through personal and written communications with individuals. NMFS considered the

solicited information from the public, a literature review, and current information regarding

pinniped sightings in the southeast U.S. and Caribbean regions to assess the possibility that this

species continues to exist in the wild. To complete the 5-year review, we evaluated all

information that has become available on the species since 1984, the date of its last biological

status review.

3

1.3 Background

1.3.1 FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review

NMFS announced initiation of the 5-year review for Caribbean monk seals (M. tropicalis) and

asked the public to submit information regarding the species' status on November 29, 2006 (71

FR 39327). Comments were received and incorporated as appropriate into the 5-year review.

1.3.2 Listing history

Original Listing (under Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966)

FR notice: 32 FR 4001

Date listed: March 11, 1967

Entity listed: entire species

Classification: endangered

Revised Listing

FR notice: 44 FR 21288

Date listed: April 10, 1979

Entity listed: entire species

Classification: endangered

1.3.3 Associated rulemaking

None.

1.3.4 Review History

Monk Seal 5-Year Review: November 9, 1984

A Caribbean monk seal 5-year review published on November 9, 1984, determined that the best

available information indicated the Caribbean monk seal is extinct. No sightings or evidence of

Caribbean monk seals have been documented since the last confirmed sighting at Seranilla Bank,

between Jamaica and the Yucatán Peninsula, in 1952. Therefore, the 5-year review

recommended that the species be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species

under the ESA (49 FR 44774). Following the 1984 status review, the U.S. Marine Mammal

Commission contracted a study to interview local fishermen, residents, and sailors along the

north coast of Haiti (Woods and Hermanson 1987). Although there were two reported seal

sightings obtained during the survey, there was no tangible evidence to confirm whether those

sightings involved Caribbean monk seals or some other species. A subsequent survey of

fishermen in waters of Haiti and Jamaica also reported oral accounts of seal sightings, but again,

there was no corroborating proof that the sightings involved seals, much less Caribbean monk

seals (Boyd and Stanfield 1998). Based on the results of these surveys, NMFS decided not to

delist the species, due the possible existence of a remnant population in the wild.

1.3.5 Species’ Recovery Priority Number at Start of 5-year Review

Because this species is likely extirpated throughout its range, the NMFS October 1, 2004-

September 30, 2006 Biennial Report to Congress on the Recovery Program for Threatened and

Endangered Species assigned the recovery priority number for the Caribbean monk seal as 12.

This represents a low magnitude of threat as a rare population, a low recovery potential, and the

absence of conflict with economic activity.

4

1.3.6 Recovery Plan or Outline

No recovery plan has been prepared for the Caribbean monk seal. Upon the species’ revised

listing under the ESA in 1979, there was no known population existing in the wild. No

information was available upon which a recovery plan could be based.

2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS

2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy

The Caribbean monk seal is a vertebrate and subject to the DPS Policy (61 FR 4722). The

species has not been sighted since 1952. There is no information to indicate there is a remaining

population of this species, much less more than one. Identification of DPS’ is not appropriate for

the Caribbean monk seal.

2.2 Recovery Criteria

Recovery plans contain downlisting and delisting criteria with regard to a species’ status and

threats. A recovery plan has not been prepared for the Caribbean monk seal because no

populations of this species were known to exist at the time of listing.

2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status

No confirmed sightings of Caribbean monk seals have been reported since the last status review

conducted in 1984. Following the 1984 review, the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission

contracted a study to interview fishermen, residents, and sailors along the north coast of Haiti

(Woods and Hermanson 1987). Although potential accounts of seal sightings were obtained

during the survey, no confirmations were obtained. However, based upon a credible account of a

sighting, some isolated animals were believed to potentially remain in some remote regions. A

subsequent survey of fisherman working in waters of the Caribbean monk seal’s former range

provided circumstantial evidence that the species may still exist in the wild (Boyd and Stanfield

1998). Since this time there has been no new information regarding this species. A review of

sightings and stranding data provided evidence of several positively identified arctic phocids in

tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Western North Atlantic from 1917 through 1996

(Mignucci-Giannoni and Odell 2001). Due to confirmed sightings of extralimital arctic species

in the Caribbean region, mostly hooded seals (Cystophora cristata), and lack of any Caribbean

monk seal sightings since 1952, the authors concluded that unidentified sightings in the period

reviewed were not Caribbean monk seals (Mignucci-Giannoni and Odell 2001). Between 1996

and 2007, 22 additional sightings of hooded seals have been confirmed in southeast U.S. waters,

of which 7 occurred in the Caribbean (Southeast U.S. Marine Mammal Stranding Database

2007).

2.3.1 Taxonomic Classification and Phylogeny:

The type specimen for the Caribbean monk seal, also known as the Caribbean seal, the West

Indian seal, and the West Indian monk seal, was described from the scientific literature in 1849

from a specimen taken in Jamaica (Gray 1849). Early references to this species referred to these

5

animals as sea wolves, hair seals, or simply seals. In Spanish, the Caribbean monk seal is known

by many names, including: cabezas de friales, foca caribeña, foca del Caribe, foca monje

caribeña, foca monje de las Antilles, foca monje del Caribe, fraile marino, lobo del mar, lobo

marino, and pez boto (Mignucci-Giannoni 1989). Although the species has several common

names, it is taxonomically described below.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Subclass: Eutheria

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Pinnipedia

Family: Phocidae

Subfamily Monachinae

Genus: Monachus

Species: tropicalis

A thorough description of the Caribbean monk seal was recently completed by Adam (2004).

The genus Monachus includes 3 allopatric species: M. tropicalis (Caribbean monk seals), M.

schauinslandi (Hawaiian monk seals), and M. monachus (Mediterranean monk seals). Caribbean

monk seals are more closely related to Mediterranean monk seals than to Hawaiian monk seals

(Wyss 1988). However, the phylogenetic relationship among monk seals remains in dispute

(Lavigne 1998). No genetic studies of Caribbean monk seals have been conducted.

2.3.2 Biology

The Caribbean monk seal has a typical seal-like appearance, with a well-developed blubber

layer, flipper-like limbs, a short tail, and a smooth body contour. The head is large and

prominent, eyes are large and light reddish-brown in color (Ward 1887), and external pinnae are

absent. Pups are born black in color and remain that way for about one year (Allen 1887b).

Adult pelage is variably dark dorsally (brown to black) and graded into a lighter yellowish-white

countershade ventrally. Ventral fur ranges from pale yellow to yellowish-gray or yellowishbrown

and is sometimes mottled with darker patches. The front and sides of the muzzle and the

edge of the full and fleshy lips are yellowish-white.

Caribbean monk seals are sexually dimorphic, with females smaller than males (Allen 1887a).

However, the size difference is slight and could not be used to distinguish between the sexes.

The two sexes are also alike in color and form (Allen 1887a). Females have 2 pairs of functional

mammae (Ward 1887). Measurements of adults of both sexes generally range between

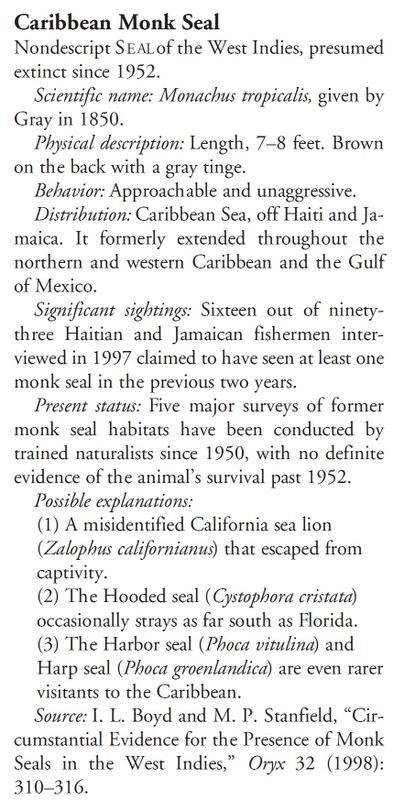

2.0-2.5 m (Allen 1887a; Allen 1887c, Ward 1887). The only known photographs of Caribbean

monk seals in the wild appear in Adam and Garcia (2003). The best photograph of this species

was taken at the New York Aquarium in 1910 (Figure 1).

6

Figure 1. A 1910 photograph of Caribbean monk seal at the New York

Aquarium. Specimen captured in Campeche Bank region as described in

Townsend (1909).

Caribbean monk seal vocalizations have been described as roaring, pig-like snorting, moaning,

dog-like barks, growls, and snarls (Gosse 1851, Hill 1843, Nesbitt 1836, Townsend 1909). Pup

vocalizations have been reported as a long, drawn out, guttural ‘‘ah’’ with a series of vocal

hitches during enunciation (Ward 1887). Underwater vocalizations of Caribbean monk seals

have not been described and are unknown. As with both Hawaiian and Mediterranean monk

seals, Caribbean monk seals apparently became sensitized to human presence after exposure to

hunting or other abusive treatment. Thus, although many recent descriptions of monk seals state

that they are highly sensitive to human disturbance, some accounts, including early accounts of

the species (e.g., E.W. Nelson, as cited in Adam and Garcia 2003), describe them as being very

approachable when hauled out on beaches.

Both Mediterranean and Hawaiian monk seals are known to consume a variety of fish,

cephalopods, and crustaceans (Marchessaux 1989, Goodman-Lowe 1998), and it has been

speculated that Caribbean monk seals have a similar diet (Nesbitt 1836, Gosse 1851, Ward

1887). The three species of Monachus have no obvious functional dental or osteological features

to suggest that their feeding habits are significantly different from each other (Adam and Berta

2002).

The incidence of disease in the wild has not been reported, but an occurrence of a condition that

may have been cataracts has been noted (Gaumer 1917, Ward 1887). The nasal mite Halarachne

americana was recovered in great numbers and in all stages of its life cycle from the respiratory

passages of a single captive specimen. The mite, which is only known from Caribbean monk

seals and has not been identified from any other species or habitats since that time, may now be

extinct (Adam 2004). Caribbean monk seals were reported to have heavy parasitic helminth

loads (Adam and Garcia 2003, Ward 1887), but a detailed description and species identification

has not been reported.

2.3.3 Life History

Most observations of life history and behavior of Caribbean monk seals are based on short-term

observations of seals in isolated colonies following heavy exploitation of the species. Due to the

decline of this species after the arrival of the Europeans in the wider Caribbean region and its

rarity by the time the species was first described in the scientific literature, remarkably little is

7

known about its life history. Prior to its depletion, Caribbean monk seals hauled out in groups of

up to 500 individuals (Nesbitt 1836). Accounts of Caribbean monk seals are usually from

isolated islands, keys, and atolls surrounded by shallow, reef-protected waters, and only

occasionally from mainland beaches. Haul out sites are usually sandy beaches that remain

exposed at high tide (Gaumer 1917 and Hill 1843, as summarized in Adam 2004, Kerr 1824,

Ward 1887), but also include near shore rocks and rocky islets (Allen 1880). Haul out sites

typically have sparse or no vegetation and no fresh water (Ward 1887). Adam and Garcia (2003)

and Ward (1887) reported that they usually hauled out on beaches to rest in the early morning,

although sometimes they would haul out and rest overnight.

Very little is known about the effects of over-exploitation on sex ratios of the species. The

male:female ratio of specimens collected during a 1900 expedition in Mexico was 24:76, but by

then the species was already severely depleted. Because such data are limited to a single sample

size from one colony, it is not possible to determine whether that reported sex ratio is

representative, reflective of previous hunting on the sex ratio of the population, or due to some

other unknown factor. The relevance of those data to life history characteristics must therefore

be interpreted with caution.

Observations of feeding seals have not been reported, and there are no reports of prey items from

the few examinations of stomach contents cited in the available literature. Pregnant females are

known only from the Triangle Keys off Mexico, where a newborn suckling pup and 5 females

with fetuses were collected in early December 1886 (Ward 1887) and a single pregnant seal was

killed in late June 1900 (original unpublished field notes of W.E. Nelson as cited in Adam and

Garcia 2003). Adam and Garcia (2003) speculate that Caribbean monk seals have low pupping

synchrony due to the limited seasonal variations in climate and prey abundance. An annual birth

rate of 15% has been calculated, but this is likely an underestimate (Rice 1973). Rice (1973)

concluded that females rarely bore young in successive years and likely produced a pup every

other year; however, research on Hawaiian monk seals (Johanos et al. 1994) and Mediterranean

monk seals (Johnson et al. 2006) has demonstrated that pupping in successive years is common

for those species. Weaning reportedly began 2 weeks after parturition; however, this also may

be an underestimate based on weaning behavior in Hawaiian and Mediterranean monk seals.

Pups apparently developed quickly (Nesbitt 1836). Subadult seals are speculated to have foraged

nocturnally in shallow, nearshore waters to avoid direct competition with adults, which fed at

dawn and dusk (Adam and Garcia 2003). Caribbean monk seals have been estimated to have a

life span of 20-30 years (Adam 2004), but long-term studies of the species in the wild are

lacking. However, this estimate is consistent with that of Hawaiian monk seals, which is thought

to have a life span of approximately 25-30 years.

2.3.4 Distribution

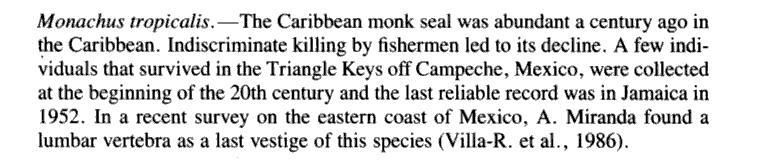

The historic distribution of Caribbean monk seals (Figure 2) has been inferred from historical

sightings, archeological records, fossil evidence, and geographical features bearing names

suggestive of their presence (Adam and Garcia 2003, Adam 2004). The species’ northernmost

record is from a fossil recovered near Charleston, South Carolina. There is evidence that

Caribbean monk seals used mainland beaches of North or Central America as haul-out sites in

great numbers. Most sightings records are from isolated islands, cays, and reefs in the eastern

Gulf of Mexico (Ray 1961, Timm et al. 1997) and western Caribbean Sea. The only evidence

Caribbean monk seals occurred in the Lesser Antilles is from archeological remains in

8

the northern end of the chain (Wing 1992) and a single sighting record (Timm et al. 1997). A

few sighting records, archeological finds, and suggestive place names extend the known range of

Caribbean monk seals to include the northern coast of South America (Timm et al. 1997 and

Debrot 2000).

Figure 2. Distribution of M. tropicalis in the western tropical Atlantic

region based on historical records (closed circles), archaeological and fossil

records (open circles), and localities with names suggestive of occurrence

(triangles) such as Lobos Cay (Cuba), Lobos Cay (Honduras) Cayo Lobo

Marino (Nicaragua), Seal Keys (Bahamas), and Isla de Lobos (Veracruz). For

a description of the source and location data used to define the distribution of

Caribbean monk seals, see Adam and Garcia 2003, Adam 2004, and Timm et

al. 1997. Figure from Adam (2004).

2.3.5 Factors Contributing to the Decline of Caribbean Monk Seals

Although documentation of harvest levels and practices that led to this species’ population

decline is nearly absent, it is evident from early reports that relatively large numbers of seals

persisted in at least some areas as late as the early 1800s and that their precipitous decline in

abundance was due to heavy exploitation by sealers and other people. During the 1800s their

distribution became increasingly fragmented. By the time scientific expeditions were organized

in the late 1800s to document and study the species, their range was already drastically curtailed.

Rice (1973) concluded that the last confirmed sighting of this species was in 1952 at Seranilla

Banks in the western Caribbean.

When determining whether a species is threatened or endangered, we evaluate the five factors

under ESA section 4(a)(1) to specify the reasons for the species’ status:

1. Present or threatened destruction, modification or curtailment of its habitat or range;

2. Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

9

3. Disease or predation;

4. Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and

5. Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

A five-factor analysis of the current threats to the species is superfluous since the species has not

been sighted in over 50 years; however, we can review the factors contributing to this species’

drastic decline. The Caribbean monk seal population was already severely depleted, and likely

extirpated throughout most, if not all, of its range prior to the passage of the ESA and Marine

Mammal Protection Act. The two main factors leading to its listing as endangered are the

modification and curtailment of its habitat and range, and overutilization for commercial and

educational purposes.

2.3.5.1 Present or threatened destruction, modification or curtailment of its

habitat or range

When hauled out on beaches, Caribbean monk seals were reported to have been sensitive to

human disturbance (Allen 1880, Gaumer 1917, Ward 1887). When disturbed, they reportedly

returned to the water where they remained until the people or vessels left the area (Adam and

Garcia 2003, Allen 1880). As human settlements expanded in areas inhabited by this species and

persistent hunting reinforced evasive seal behaviors, avoidance of human presence near

populated shorelines and areas regularly visited by fishermen likely caused seals to abandon

historic haul-out sites. Human encroachment also likely exacerbated stresses on the population

as it declined. Although the species was reported as common in the early to mid-1700s, it was

already considered rare by the mid-1880’s (Allen 1887b, Elliot 1884, Gratacap 1900).

2.3.5.2 Overutilization for Commercial and Educational Purposes

Caribbean monk seals were utilized as a source of meat by early mariners and heavily exploited

as a source of oil following European colonization (Allen 1880). Other human-caused factors

such as entanglement and drowning in fishing nets and slaughter by fishermen viewing the seals

as competitors for fish contributed to their decline (Rice 1973). Caribbean monk seals were also

killed for scientific collection and study, as well as for display in zoological gardens. Adam

(2004) provides an excellent review on the historical exploitation of Caribbean monk seals. He

reports the species was the most readily exploited source of oil in the tropical West Atlantic

Ocean prior to the early 1800s, and that they were hunted to near extinction for their blubber

until the early 1900s.

Blubber was processed and used for lubrication, coating the bottom of boats, and as lamp and

cooking oil. Caribbean monk seal skins were sought to make trunk linings, articles of clothing

(e.g., caps and belts), straps, and bags. In the early 1700s, a girdle fashioned from a Caribbean

monk seal pelt was believed to relieve lower back pain. At least some sailors reportedly prized

monk seal pelts believing that their hairs became erect during rough seas, but remained flat in

calm seas. The Swiss naturalist Konrad Gesner reported accounts from seafarers in the

Caribbean (near the island of Hispaniola) in the 1550s, writing: “Its hair is reputed to be of such

a wondrous nature that the skins or belts are worn by mariners. When thunderstorms, tempests

and other inclement weather is nigh, the hair shall rise and bristle, but when it turns still and

mild, it shall lay down smoothly” (Gesner 1558, as cited in Johnson 2004).

10

Caribbean monk seals were taken for food by sailors stranded on the Arricifés Viboras (Cuba) in

1520, on the Islas de Lobos (Veracruz, Mexico) in 1524, Dry Tortugas (Florida) in 1742, and in

the Triangle Keys (Mexico) in 1846. Guano gatherers visiting the Triangle Keys in 1856

reportedly made a bonfire of 100 barrels of Caribbean monk seal skins and skeletons left behind

by sealers, suggesting that they were heavily exploited for their oil in this region. Fishermen

sometimes hunted the seals for meat until about 1885. In at least one instance, two monk seals

were killed simply ‘‘for fun’’ (Allen 1880). Aside from heavy hunting pressure by humans, the

only known natural predator reported is an unidentified species of shark (Fernández de Oviedo

1944).

As a result of this species’ increasing rarity in the wild, live specimens were eagerly sought by

zoological gardens following the discovery of remnant populations in the late 1800s. In 1897,

two live specimens sold for $50.00 each, and dead or mounted specimens also were sold to

museums. Two scientific expeditions to the Triangle Keys are believed to have contributed to

the extirpation in that region. On four days in December 1886, 49 seals were killed in the

Triangle Keys (Allen 1887, Ward 1887). Live specimens obtained by the New York Aquarium

in 1897 and 1909 also were captured from the Triangle Keys (Townsend 1909).

2.4 Synthesis

Since passage of the ESA, several efforts have been made to investigate unconfirmed reports of

the species in or near the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, the Southern Bahamas, and Atlantic

coast of the Greater Antilles. There have been several reports of pinnipeds within the range of

Caribbean monk seals since the last authoritative sighting at the Seranilla Banks in 1952.

Unconfirmed sightings of pinnipeds up to that time resulted in speculation that the Caribbean

monk seal still existed in a few, isolated colonies as late as the mid 1900s. The historical

accounts of the species, unsuccessful expeditions to locate remnant colonies, and confirmed

sightings of pinniped species other than Caribbean monk seal within the species’ historical range

now provide useful perspective on the species’ decline. The following provides a brief historical

account of sightings and survey efforts for the species.

1494: The first sightings records of Caribbean monk seals were made during the second voyage

of Columbus, when 8 individuals were killed for their meat (Kerr 1824).

1700s to 1900s: Caribbean monk seals were exploited intensively for their oil, and to a lesser

extent for food, scientific study, and zoological collection following European colonization.

1886: Caribbean monk seals were reported to occur in the Triangle Keys in the Gulf of

Campeche, where 49 seals were killed during a scientific expedition. (Ward 1887)

1897: The New York Aquarium acquired two specimens captured from the Triangle Keys.

(Townsend 1909)

1906: On February 25, 1906, fishermen killed a Caribbean monk seal five miles off Key West,

Florida. The 1906 account was the first sighting of the species in Florida in approximately 30

years. (Townsend 1906)

11

1909: The New York Aquarium received four live Caribbean monk seals from a dealer in

Progresso, Yucatán. At the time, the last known population of the Caribbean monk seal was

restricted to islands and reefs off the Yucatán, Mexico. (Townsend 1909)

1922: A monk seal was killed by a fisherman near Key West, Florida, on March 15, 1922. This

was the last confirmed sighting of the seal in the United States. Townsend noted a small

breeding colony still remained in the Triángulos reef group (i.e., the Triangle Islands) in the

Campeche Bank islands off Mexico (Townsend 1923)

1932: Following interviews with men having seen seals in the lower Laguna Madre region of

Texas, Gordon Gunter concluded that a few Caribbean monk seals were scattered along the

Texas coast as late as 1932 (Gunter 1947). It was later suggested that the sightings of seals along

the Texas coast were probably feral California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) (Gunter 1968).

1952: C.B. Lewis observed the last authoritative sighting of Caribbean monks at a small seal

colony off Seranilla Banks (Colombia) in 1952, located between Jamaica and the Yucatán

peninsula. (Rice 1973)

1973: The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) distributed circulars in

both English and Spanish throughout the Caribbean region in 1973, offering U.S. $500 for

information on recent sightings of the species. No confirmed sightings were made. (Boulva

1979)

1973: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service conducted aerial surveys off the Yucatán, south to

Nicaragua, and east to Jamaica of all the areas where Rice suggested that Caribbean monk seals

may still exist. The species was not sighted in the survey area. (Kenyon 1977)

1980: Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Arctic Biological Station supported a

search for evidence of Caribbean monk seals in remote islands of the southeastern Bahamas by

vessel and interviews with local fishermen. The vessel survey produced no sightings of seals.

Interviews with fishermen produced a few new accounts of seals in the area during the 1960s and

1970s, but the sightings could not be confirmed as Caribbean monk seals. (Sergeant et al. 1980)

1984: From September 5-15, 1984, a survey was conducted across the Gulf of Mexico to

Campeche, Mexico, aboard the Scripps Institution of Oceanography research vessel, Robert G.

Sproul. The survey crew landed at three island groups off the north coast of the Yucatán

Peninsula considered possible haul-out sites still used by monk seals: Islas Triangulos, Cayo

Arenas and Arrecife Alacran. Another island, Cayo Arcas, was visited by helicopter on

September 7, 1984. The survey yielded no seal sightings or evidence of their continued

existence. (LeBoeuf et al. 1986)

1985: The United States Marine Mammal Commission contracted for a survey of local

fishermen, coastal residents, and sailors in northern Haiti. Two of 77 people interviewed

reported having seen a seal, one of which - a sighting at Île Rat in the Baie de l’Acul in 1981-

was considered a reliable account. In neither case, however, was it possible to confirm the

sighting as a Caribbean monk seal. (Woods and Hermanson 1987)

12

1996: The IUCN Seal Specialist Group listed the Caribbean monk seal as extinct on its Red List

of threatened and endangered species. (Seal Specialist Group 1996)

1997: Based on interviews with 93 fishermen in northern Haiti and Jamaica during 1997, it was

concluded that there was a likelihood that Caribbean monk seals may still survive in this region

of the West Indies. Fishermen were asked to select marine species known to them from

randomly arranged pictures: 22.6% (n=21) selected monk seals of which 78% (n=16) had seen at

least one in the past 1-2 years. (Boyd and Stanfield 1998)

2001: A review of seal sightings and marine mammal stranding data in the Southeast U.S. and

Caribbean region documented evidence of several pinnipeds positively identified as arctic

phocids between 1917 through 1996 that had strayed into the tropical and subtropical waters of

the Western North Atlantic. Due to confirmed sightings of extralimital arctic species, mostly

hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Caribbean region, confirmed sightings and recaptures

of feral California sea lions Zalophus californianus) that had escaped from captivity, and lack of

any confirmed Caribbean monk seal sightings since 1952, the authors concluded that

unidentified sightings since 1952 were likely species other than Caribbean monk seals.

(Mignucci-Giannoni and Odell 2001)

2007: Between 1996 and 2007, 22 additional, confirmed sightings of hooded seals have been

reported from the tropical and subtropical waters of the Western North Atlantic, including seven

from the Caribbean Sea. (Southeast U.S. Marine Mammal Stranding Database data 2007)

Although Caribbean monk seals could be cryptic while at sea and a low number of individuals in

a population may lower the detectability of individuals, hauled out individuals at rest or females

with pups would be conspicuous to an observer. The United Nations Environment Programme,

Caribbean Environment Programme was contacted in December 2007 regarding any new

information on surveys or sightings of Caribbean monk seals that may have been missed by

NMFS review of sightings and stranding data; however, the inquiry resulted in no new

information. With pervasive human presence in the wider Caribbean region and the necessity for

seals to haul-out to rest and pup, it would be expected that any remaining individuals in the wild

would have been sighted and confirmed over the past 50 years. Furthermore, there are few, if

any, remaining areas where Caribbean monk seals were known to occur that have not been

frequented by at least periodic human visits (e.g., fishing activities, recreational activities, and

scientific expeditions). No Caribbean monk seal sightings have been reported from the

numerous scientific surveys conducted in the former range of the species (e.g., avian nesting

colonies, sea turtle nesting beaches, coral reef studies, and other biological and ecological

research). Fishermen, shrimping boats, and abandoned camps have been ubiquitous throughout

the species’ known hauling grounds for decades (Kenyon 1977, LeBoeuf et al. 1986).

Because the range of Caribbean monk seals lies well outside the normal distribution of all other

pinnipeds, sightings of seals are remarkable events in the wider Caribbean region. However,

NMFS’ analysis of stranding data shows that the extralimital occurrence of arctic phocids occurs

with some regularity. Current technology allows for near real-time communication when such

rare or unusual species are sighted. Better methods also exist to confirm species identification

13

when such sightings are made (e.g., photographs and genetic analysis of tissue samples).

Although some seal sightings inevitably are not identifiable to a particular species, all those that

have been confirmed in recent decades within the known range of the Caribbean monk seal have

proven to be other species, namely feral California sea lions (Rice 1973), manatees (Trichechus

manatus), or hooded seals (Mignucci-Giannoni and Odell 2001, NMFS Southeast U.S. Marine

Mammal Stranding Database data 2007). The extralimital occurrence of juvenile hooded seals in

subtropical and tropical waters occurs with enough frequency to account for most recent

pinniped sightings within the former range of the Caribbean monk seal (Mignucci-Giannoni and

Haddow 2002, Mignucci-Giannoni and Odell 2001).

A sufficient amount of time has passed since the last sighting of this species to make an

inference on the status of this species. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered

Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the World Conservation Union have set 50 years

with no sightings as the cut-off for species extinction (World Conservation Union 1982). In

1949, the International Conference on the Protection of Nature (United Nations Scientific

Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources) included the Caribbean monk seal

in a list of 14 mammals whose survival was considered to be a matter of international concern

requiring immediate protection (Westermann 1953). However, the last confirmed sighting of the

species occurred in 1952, limiting any opportunity for conservation efforts of any remaining

animals in the wild. It has been over 50 years since the last confirmed sighting of Caribbean

monk seals in the wild despite multiple survey efforts to locate the species. Solow (1993)

utilized survey data of Caribbean monk seals to demonstrate statistically that the likelihood of

extinction is high based on the lack of sightings of this species. The International Union for the

Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources concluded the Caribbean monk seal was extinct

in 1996 (Seal Specialist Group 1996), but the species remained listed under the ESA in the

United States based on a possibility that some Caribbean monk seals persisted for a few years

after their last confirmed sighting in 1952 at Seranilla Bank.

Although there were no sightings, it is possible that the Caribbean monk seal persisted for a short

period in the years following the last confirmed sighting in 1952 at Seranilla Bank. If so, with an

estimated life span of 20-30 years, some individuals may have possibly persisted into the 1960’s

or 1970’s. If any remnant population did survive, it seems likely they consisted of scattered

individuals, with no remaining colonies large enough to be viable in the wild. Considering the

absence of confirmed seals sightings since 1952, the fact that all confirmed seal sightings have

been of other species, and the ubiquitous presence of humans throughout the species’ range, the

Caribbean monk seal appears to have been extirpated before any meaningful conservation and

recovery efforts could be taken for the species.

We believe our review has complied with the statutory requirements of section 4(a), 4(b), and

4(c)(2) of the ESA. Based upon our review of the status of this species, we conclude that the

Caribbean monk seal is extinct, primarily due to human exploitation.

14

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Recommended Classification

Although there have been recent reports of seal sightings within the historical range of Caribbean

monk seals, all verified sightings have involved accounts of other pinnipeds outside their normal

range or misidentified manatees. Based on review of the best available information, there have

been no confirmed sightings of Caribbean monk seals since 1952. We can find no new

information to support a conclusion that this species may continue to exist in the wild.

Therefore, it is recommended that the Caribbean monk seal be delisted due to extinction.

____ Downlist to Threatened

____ Uplist to Endangered

_��_ Delist (Indicate reasons for delisting per 50 CFR 424.11):

_��_ Extinction

____ Recovery

____ Original data for classification in error

____ No change is needed

3.2 New Recovery Priority Number:

No change is needed until delisting actually takes place.

Brief Rationale: The species’ current recovery priority number is 12, representing a low

magnitude of threat as a rare population, a low recovery potential, and the absence of

conflict with economic activity.

3.3 Listing and Reclassification Priority Number: _ 1

Delisting Priority Number: 6 1

4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIONS

This status review concludes the Caribbean monk seal is extinct. It is recommended this species

be removed from the Endangered Species Act list of threatened and endangered species through

the rulemaking process. Although no future management actions are required, genetic samples

should be isolated from bones and pelts in existing scientific collections for future reference and

analysis. Genetic characterization of the species should occur while good samples of the species

remain available.

15

5.0 REFERENCES

Adam, P. J., and A. Berta. 2002. Evolution of prey capture strategies and diet in

Pinnipedimorpha (Mammalia, Carnivora). Oryctos 4:83–107.

Adam P. J., G. G. Garcia. 2003. New information on the natural history, distribution,

and skull of the extinct (?) West Indian monk seal, Monachus tropicalis Marine

Mammal Science 19:297–317.

Adam, P.J. 2004. Monachus tropicalis. Mammalian Species 747:1-9. American Society

of Mammalogists.

Allen J. A. 1887a. The West Indian seal (Monachus tropicalis Gray). Bulletin of the

American Museum of Natural History 2:1–34.

Allen J. A. 1887b. The West Indian seal. Science 9:35.

Allen J. A. 1887c. The West Indian seal. Science 9:59.

Boulva, J. 1979. Caribbean monk seal. Pp. 101–103 in Mammals in the seas: report of the FAO

advisory committee in marine resources research, working party on marine mammals.

Pinniped species summaries and report on sirenians. Food and Agriculture Organization of

the United Nations, Rome, Italy 2:1–151.

Boyd. L. and M.P. Stanfield. 1998. Circumstantial evidence for the presence of monk

seals in the West Indies. Oryx 32(4):310-316.

Debrot A. O. 2000. A review of records of the extinct West Indian monk seal,

Monachus tropicalis (Carnivora: Phocidae), for the Netherland Antilles. Marine

Mammal Science 16:834–837.

Elliott H. W. 1884. The monk seal of the West Indes, Monachus tropicalis Gray. Science

3:752–753.

Federal Register. “Endangered Species List – 1967.” Federal Register 32 (11 March

1967):4001.

Federal Register. “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (Conservation of Endangered Species

and Other Fish or Wildlife).” Federal Register 35 (30 July 1970):12222-12225.

Federal Register. “Proposed Listing, Endangered Caribbean Monk Seal, Proposed

Endangered Status.” Federal Register 42 (16 February 1977):9402-9403.

Federal Register. “Caribbean Monk Seal; Listing as an Endangered Species, Final

Listing.” Federal Register 44 (10 April 1979):21288-21289.

16

Federal Register. “Review of Marine Mammals, Sea Turtles, and Marine Fishes Listed as

Endangered or Threatened.” Federal Register 49 (9 November 1984):44774-44775.

Federal Register. “Endangered and Threatened Species; Initiation of 5-Year Review of

the Caribbean Monk Seal.” Federal Register 71 (29 November 2006):69100-69101.

Fernández de Oviedo, G. 1944. Historia general y naturel de las Indias: islas y tierra-firme del

mar Oce´ano. Editorial Guarania, Asuncion, Paraguay 3:1–319.

Gaumer, G. F. 1917. Monographía de los mamíferos de Yucatán. Departmento de Talleres

Gráficos de la Secretaría de Fomento, Mexico City, Mexico.

Geser, Konrad. Historia Animalium. 1558.

Gratacap L. P. 1900. The Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Science

9:807–816.

Goodman-Lowe, D.G. 1998. Diet of the Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi) from

the northwestern Hawaiian islands during 1991 to 1994. Marine Biology 132:535-546.

Gosse, P. H. 1851. A naturalist's sojourn in Jamaica. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans,

London.

Gray, J.E. 1849. On the variation in the teeth of the crested seal, Crystophora critata, and on a

new species of the genus from the west Indies. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of

London 17:91-93.

Gunter G. 1947. Sight records of the West Indian monk seal, Monachus tropicalis

(Gray), from the Texas coast. Journal of Mammalogy.

Gunter, G. 1968. The status of seals in the Gulf of Mexico, with a record of feral otariid seals

off the United States Gulf coast. Gulf Research Reports 2:301–308.

Hill, R. 1843. The black seal of the Pedro Shoals. Pp. 62–67 in The Jamaica almanack for 1843,

being the third after bissextile or leap year, and the 350th since the discovery of the island by

Columbus. Companion to almanack (W. Cathcart, ed.). William Cathcart, Kingston, Jamaica.

Johanos, T.C., B.L. Becker, and T.J. Ragen. 1994. Annual reproductive cycle of the female

Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi). Marine Mammal Science 10:13-30.

Johnson, W.M. 2004. Monk seals in post-classical history. The role of the Mediterranean monk

seal (Monachus monachus) in European history and culture, from the fall of Rome to the

20th century. Mededelingen 39. Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection,

Leiden.

Johnson, W.M., A.A. Karamanlidis, P. Dendrinos, P. Fernández de Larrinoa, M. Gazo, L.M.

17

Mariano González, H. Güçlüsoy, R. Pires, M. Schnellmann. 2006. Monk Seal Fact Files.

Biology, Behaviour, Status and Conservation of the Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus

monachus. The Monachus Guardian,http://www.monachusguardian.

org/factfiles/medit1904.htm.

Kenyon, K. W. 1977. Caribbean monk seal extinct. Journal of Mammalogy 58:97-98.

Kerr, R. 1824. General history and collection of voyages and travels, arranged in systematic

order: forming a complete history of the origin and progress of navigation, discovery, and

commerce, by sea and land, from the earliest ages to the present time. William Blackwood,

Edinburgh, Scotland 3:1–503.

Lavigne, D.M. 1998. Historical biogeography and phylogenetic relationships among

modern monk seals, Monachus spp. Monachus Science. The Monachus Guardian, Vol.1 No.2,

December 1998.

www.monachus-monachus-guardian.org/mguard02/02scien2.htm.

Leboeuf, B.J., Kenyon, K.W., and B. Villa-Ramirez. 1986. The Caribbean monk seal is

extinct. Marine Mammal Science 2(1):70-72.

Marchessaux, D. 1989. The biology, status and conservation of the monk seal (Monachus

monachus). Parc national de Port-Cros, Hyeres, France.

Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A. 1989. Zoogeography of marine mammals in Puerto Rico and the

Virgin Islands.

Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A. & Haddow, P. 2001. Caribbean monk seals or hooded seals?

The Monachus Guardian. Vol. 4 (2): November 2001.

www.monachus-guardian.org/mguard08/08newvar.htm.

Mignucci-Giannoni A.A. and P. Haddow. 2002. Wandering hooded seals. Science 295(5555):

627-628.

Mignucci-Giannoni A. A., D. K. Odell. 2001. Tropical and subtropical records of

Hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) dispel the myth of the extant Caribbean monk

seals Monachus tropicalis). Bulletin of Marine Science. 68:47–58.

Monachus. 1999. Profiles: Caribbean Monk Seal, Monachus tropicalis. Downloaded on

24 April 2006 from

www.monachus.org/profiles/cariseal.htm.

Nesbit, C.R. 1836. On the Bahamas fisheries. Journal of the Bahama Society for the

Diffusion of Knowledge 183'6: 126-136.

Ray C. E. 1961. The monk seal in Florida. Journal of Mammalogy 42:113.

Rice, D. W. 1973. Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis). Pp. 98–112 in

18

Proceedings of a working meeting of seal specialists on threatened and depleted seals of the

world, held under the auspices of the survival service commission of the IUCN. University of

Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 18–19 August 1972. International Union for Conservation of Nature

and Natural Resources, Morges, Switzerland.

Seal Specialist Group. 1996. Monachus tropicalis. In: IUCN 2004. 2004 IUCN Red List

of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 18 October 2006.

Sergeant, D, G. Nichols, and D. Campbell. 1980. Expedition of the R/V Regina Maris tp Search

for Caribbean Monk Seals in the South East Bahamas Islands, April 13-26, 1980. Pages 41-

44 in K. Ronald, ed. Newsletter of the League for the Conservation of the Monk Seal, no. 5.

Solow A. R. 1993. Inferring extinction from sighting data. Ecology 74:962–964.

Swanson, G. 2000. Final millenium for the Caribbean monk seal. The Monachus Guardian 3(1):

May 2000. Available at http:www.Monachus-guardian.org/mguard05/05infocu.htm.

Timm R. M., R. M. Salazar, T. Peterson. 1997. Historical distribution of the extinct

tropical seal, Monachus tropicalis (Carnivora: Phocidae). Conservation Biology 11:549–551.

Townsend C. H. 1906. Capture of the West Indian seal (Monachus tropicalis) at Key

West, Florida. Science 23:583.

Townsend C. H. 1909. The West Indian Seal at the aquarium. Science 30:212.

Townsend C. H. 1923. The West Indian seal. Journal of Mammalogy. 4:55.

Ward H. L. 1887. Notes on the life-history of Monachus tropicalis, the West Indian seal.

American Naturalist. 21:257–264.

Westerman, J. H. 1953. Nature preservation in the Caribbean. Foundation for Scientific

Research in Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Wing, E. S. 1992. West Indian monk seal: Monachus tropicalis. Pp. 35–40 in Rare and

endangered biota of Florida. Mammals (S. R. Humphrey, ed.). University Press, Gainesville,

Florida. WING, E. S. 2001a. Native American use of animals in the Caribbean.

Woods, C.A and J.W. Hermanson. 1987. An investigation of possible sightings of

Caribbean monk seals (Monachus tropicalis), along the north coast of Haiti. Final Report to

the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission in Fulfillment of Contract MM3309519-2.

World Conservation Union. 1982. The IUCN Amphibia-Reptilia red data book, part 1. Gland,

Switzerland.

Wyss, A. R. 1988. On "retrogression" in the evolution of the Phocinae and phylogenetic

affinities of the monk seals. Am. Museum Nov. 2924:1-3.

19

sero.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdf/M_tropicalis_5_year_review_March_2008.pdf