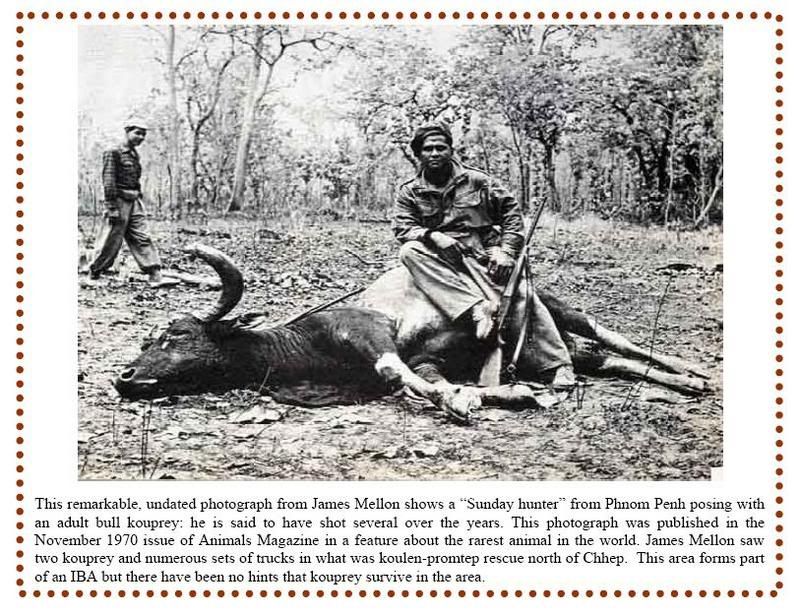

A Celebrity Among Ungulates May Soon Be Dismissed

In the 1930's, the kouprey trotted like a revelation out of the forests of

central Indochina and into the world of modern science. Here, after all, was

a large wild ox with the speed and grace of a deer and an impressive set of

horns, yet it had been hiding in plain view, having never been officially

discovered by science.

But now, just 70 years after the first captive kouprey was sent to France

from Cambodia for study, the last species of wild Asian cattle to become

known scientifically may become the first to vanish in modern times - and

not necessarily through extinction. Rather, three biologists from

Northwestern University and the Cambodian Forestry Administration have

proposed a taxonomic demotion. In a paper published online in July by The

Journal of Zoology, they say the kouprey (koh-PRAY) is probably a domestic

hybrid that became feral, a zoological poseur, not a valid species.

The biologists' proposal has met stiff opposition within the small group of

scientists who study Asian wild cattle. Several say the paper misinterpreted

the genetics and history of the kouprey, which may still exist in

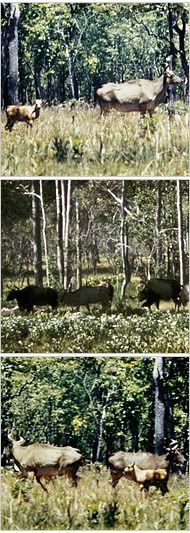

domesticated form. Although rare, elusive and enigmatic, kouprey are

recognizable enough, longer-legged, more graceful, faster and slightly

larger than the closely related banteng, and slightly smaller than the gaur,

the largest of the wild cattle.

Kouprey bulls stand just over six feet tall and weigh up to 1,800 pounds,

with a humpback, a dewlap - the loose fold of skin dangling from the neck -

that can drag the ground and elaborate curved horns. Females are about

three-quarters the size of males, have little or no dewlap, and their horns

spiral at the ends. Kouprey are probably extinct in the wild, victims of

overhunting, war and habitat loss. There have been no confirmed sightings in

more than 20 years, and even unconfirmed sightings have been rare since the

1990's. There are no kouprey in any of the world's zoos.

But if the kouprey is not a species, then the word "extinction" does not

have its usual meaning. Or as Gary J. Galbreath, the lead author of the

paper, put it in an e-mail message, "It is pleasant to realize that humans

have probably not, after all, caused the extinction of a species in this

case."

In their Journal of Zoology paper, Dr. Galbreath and his colleagues say the

kouprey most likely originated as a cross between two domesticated species,

the banteng and the zebu. Dr. Galbreath said in an interview that the animal

might have become wild in the 19th century as a result of the societal

disruption that followed an invasion of Cambodia by Thailand, then called

Siam. Although the kouprey reproduced in the wild, they were in decline

almost from the moment of their escape from domesticity.

The researchers say their conclusions are based on analysis of mitochondrial

DNA, or DNA inherited only from the mother, taken from two living Cambodian

banteng and from the taxidermic remains of that first captive kouprey

shipped to France in 1936.

Essentially, they found that the mitochondrial DNA sequence of the kouprey

matched that of the Cambodian banteng, indicating a common maternal

original. Anticipating criticism, Dr. Galbreath and his colleagues

considered two alternative interpretations. A vast genetic mixing hundreds

of thousands of years ago involving banteng and a zebu-like wild ox could

have produced the kouprey, they said, but that was unlikely because such

events were rare, and there was no evidence that the wild ox existed.

It is also possible the kouprey was a naturally occurring species whose

females, as its numbers declined, mated occasionally with banteng. But the

researchers doubt that could have produced two captive banteng with kouprey

mitochondria.

Here is the twist: in 2004, two French scientists, Alexandre Hassanin and

Anne Ropiquet of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, sequenced

the taxidermic kouprey's DNA to show that the kouprey was a natural species,

not a hybrid. They posted the sequence in a public genetic data bank, where

it was available to Dr. Galbreath's team, which turned the French scientists

' conclusion on its head.

Dr. Hassanin and Dr. Ropiquet have fired back. In a recently submitted

paper, they argue hypothetically that if the Cambodian banteng represents a

separate species from the Javan banteng, then the kouprey could have derived

from the Cambodian version, as the Galbreath team proposes. But it was more

likely, Dr. Hassanin said in an e-mail message, that the kouprey was a

natural species that evolved in Southeast Asia. On at least one occasion

more than 100,000 years ago, a kouprey mated with a banteng. Their

descendants are Cambodia's banteng, with mitochondrial DNA more closely

resembling kouprey than banteng.

To complicate matters further, last February Dr. Hassanin and other

colleagues published a paper in the journal Comptes Rendus Biologies arguing

that a specimen mounted in 1871 in Paris and thought to be a domestic ox

from Indochina was, in fact, a domesticated kouprey. The specimen has been

at the museum in Bourges since 1931.

Dr. Hassanin said several indigenous Asian breeds of cattle might be derived

from kouprey. Herds, especially in Cambodia, should be tested to see whether

any are pure kouprey, Dr. Hassanin and his colleagues said, adding that if

they are, steps should be taken to preserve them.

Where Dr. Hassanin sees pure kouprey, Dr. Galbreath finds his banteng-zebu

hybrid. Independently, both say that more extensive sampling and analysis of

mainland banteng are needed to determine who is correct. Commenting on the

papers, Simon Hedges, an Asian cattle specialist with the Wildlife

Conservation Society who was not involved in either study, tended to agree

that the Cambodian banteng had probably hybridized with the kouprey. But he

also suggested that the kouprey both groups studied might itself have been a

banteng-kouprey cross.

"A key message to take out of this debate is that the same forces -

overhunting, war, habitat fragmentation and loss - that caused the likely

extinction of the kouprey are still at work on other species, such as the

banteng," Mr. Hedges said. "The challenge is to keep them from suffering the

same fate as the kouprey, whatever it was."