Post by another specialist on Feb 10, 2007 8:39:50 GMT

According to Chinese legend, this graceful freshwater dolphin is the reincarnation of a drowned princess. It has been declared a national treasure of the highest order, but the Yangtze River is today one of the world’s busiest and most degraded waterways, and for over two decades conservationists have recommended that the species can only be protected by establishing an ex situ breeding population in an oxbow lake away from the main Yangtze channel. However, despite extensive debate by international conservation organisations, little active work has ever been carried out to protect the rapidly declining population. A recent range-wide survey was unable to find any surviving baiji left in the river.

Evolutionary Distinctiveness

Traditionally river dolphins were grouped together into a single family, Platanistidae. However, genetic studies have shown that they represent a convergent group of only distantly related species, which are superficially similar to one another – for example, having reduced eyes - because they have each evolved in similar riverine environments. The baiji is now known to have diverged from Amazon and Indian river dolphins some 20-25 million years ago, and is considered to be the sole representative of the Lipotidae, an entire family of cetaceans.

Description

Size:

Head and body length:

Male: 141-216 cm

Female: 185-253 cm

Weight:

Male: 42-125 kg

Female: 64-167 kg

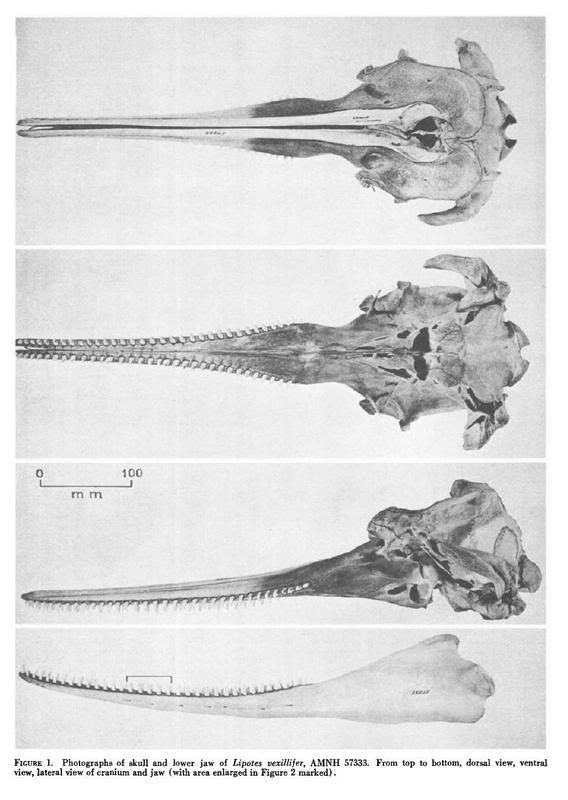

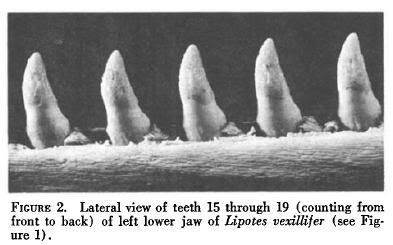

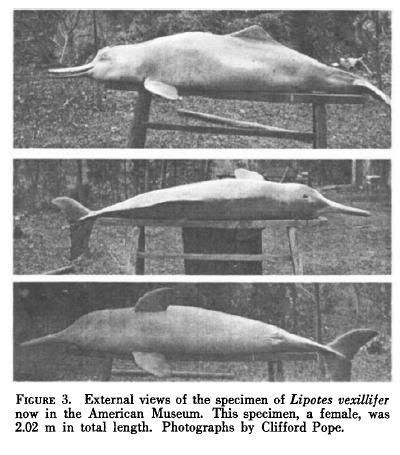

The baiji is a graceful freshwater dolphin, characterised by a very long, slightly upturned beak and low triangular dorsal fin. Like other river dolphins, it has little need for vision in the muddy waters it inhabits, and as a result has tiny, barely functional eyes. It is pale blue-grey in colour with a white underside. The female is generally larger than the male.

Ecology

Group size is usually small (four or five animals), although aggregations of up to eleven individuals have been seen in areas of abundant prey density. Sightings over the past 15 years have been extremely infrequent, typically of pairs or solitary individuals, reflecting the species' precipitous decline. Baiji feed in the early morning or during the night. There is evidence to suggest that baiji movements are linked to seasonal changes in water level, with individual baiji travelling up to several hundred kilometres upstream and downstream. Females reach maturity at eight years and give birth to one young approximately every two years. One captive male baiji, 'Qi-Qi', survived in the Wuhan dolphinarium for over 22 years. The dolphins are not heavily scarred and there is little evidence of aggressive interactions either intraspecifically or with finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis), the other small cetacean present in the mid-lower Yangtze

Habitat

Found most commonly in confluences (where rivers or streams converge with the main Yangtze channel) and around sandbars with large eddies, where fish are more abundant.

Distribution

Endemic to the Yangtze Basin in eastern China. The species has recently only been recorded from the 1700 km stretch of the middle and lower Yangtze River between Yichang and Shanghai; this historical distribution has always been downstream of the site of the Three Gorges Dam project. Until the 1950s the species was also present in the Qiantang River.

Population Estimate

A series of surveys conducted between 1997 and 1999 provided a minimum population estimate of only 13 individuals. Although a number of unverifiable opportunistic sightings have been reported by local fishermen over the past few years, a recent November-December 2006 international range-wide survey failed to find any surviving animals in the Yangtze, and it is likely that the species is now extinct.

Population Trend

Survey results indicate that numbers have declined rapidly and continuously over the past 30 years, from an estimated 400 animals in 1980 to only 100 animals in 1990. The population decrease has been estimated to be roughly 10% per annum.

Status

The baiji is classified as Critically Endangered (CR C2a(ii); D) on the 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. If it still survives, it is the world’s rarest and most threatened cetacean species.

Threats

The main threats to the survival of the species are from the massive human impacts on the degraded Yangtze ecosystem. Over 400 million people live within the Yangtze River catchment, and the riverbanks are lined with large, industrialised cities. The river is one of the world’s busiest waterways, and is heavily utilised for transport, fishing and industrial development. Probably the major cause of mortality is accidental by-catch from gill-nets, and illegal rolling hook lines and electro-fishing (which were both banned two decades ago in China because they kill dolphins, but which are still widely used along the Yangtze). Other deaths have resulted from collisions with boats, and engineering explosions for maintaining navigation channels. The Yangtze’s environment has been further degraded by pollution, upstream damming and dredging. In particular, the recently completed Three Gorges Dam is likely to affect downstream fish stocks and further reduce areas of suitable habitat. Population fragmentation is also likely to have affected any surviving baiji individuals.

Conservation Underway

The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and regional Yangtze authorities have imposed restrictions on harmful fishing and waste discharge in the river, and have officially designated a series of baiji reserves in the main Yangtze channel between Honghu and Zhejiang. However, there has been little effort to enforce these conservation measures, and there is no apparent difference between levels of legal and illegal fishing in the baiji reserves and in the remainder of the river. Despite being listed on Appendix I of CITES and having been a protected species in China since 1975, surveys carried out over the past twenty years have indicated a continuous decline in population size.

Conservation Proposed

More drastic conservation measures have been advocated since the mid 1980s, and Chinese and international scientists and policy makers have consistently recommended the removal and translocation of baiji from the Yangtze to a safer environment, to establish a closely monitored ex situ breeding programme under semi-natural conditions. This strategy has also been recommended at a series of international conservation workshops held in China and abroad over the past two decades. The initial site suggested for this breeding population was the Tongling semi-natural reserve in Anhui Province, but most recent attention has focused on the Tian'e-Zhou semi-natural reserve near Shishou City in Hubei Province, a 21 km oxbow which used to be part of the main Yangtze channel until 1972. Chinese authorities are also keen to establish a baiji population in the Wuhan dolphinarium, which now supports a breeding population of Yangtze finless porpoises.

Unfortunately, despite the apparent commitment expressed to the species by several major conservation organisations, almost no funds have ever been provided by the international community to initiate any active conservation action for the species. The only active efforts to establish an ex situ population were conducted in 1995, when a Chinese team translocated a single baiji to Tian'e-Zhou. Sadly this animal died a few months after being released in the reserve. As the baiji may now be extinct, the only remaining conservation option is to conduct a wide-range series of interviews with fishermen along the Yangtze, to try and ascertain whether any baiji still survive in the river.

www.edgeofexistence.org/species/species_info.asp?id=1

Evolutionary Distinctiveness

Traditionally river dolphins were grouped together into a single family, Platanistidae. However, genetic studies have shown that they represent a convergent group of only distantly related species, which are superficially similar to one another – for example, having reduced eyes - because they have each evolved in similar riverine environments. The baiji is now known to have diverged from Amazon and Indian river dolphins some 20-25 million years ago, and is considered to be the sole representative of the Lipotidae, an entire family of cetaceans.

Description

Size:

Head and body length:

Male: 141-216 cm

Female: 185-253 cm

Weight:

Male: 42-125 kg

Female: 64-167 kg

The baiji is a graceful freshwater dolphin, characterised by a very long, slightly upturned beak and low triangular dorsal fin. Like other river dolphins, it has little need for vision in the muddy waters it inhabits, and as a result has tiny, barely functional eyes. It is pale blue-grey in colour with a white underside. The female is generally larger than the male.

Ecology

Group size is usually small (four or five animals), although aggregations of up to eleven individuals have been seen in areas of abundant prey density. Sightings over the past 15 years have been extremely infrequent, typically of pairs or solitary individuals, reflecting the species' precipitous decline. Baiji feed in the early morning or during the night. There is evidence to suggest that baiji movements are linked to seasonal changes in water level, with individual baiji travelling up to several hundred kilometres upstream and downstream. Females reach maturity at eight years and give birth to one young approximately every two years. One captive male baiji, 'Qi-Qi', survived in the Wuhan dolphinarium for over 22 years. The dolphins are not heavily scarred and there is little evidence of aggressive interactions either intraspecifically or with finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis), the other small cetacean present in the mid-lower Yangtze

Habitat

Found most commonly in confluences (where rivers or streams converge with the main Yangtze channel) and around sandbars with large eddies, where fish are more abundant.

Distribution

Endemic to the Yangtze Basin in eastern China. The species has recently only been recorded from the 1700 km stretch of the middle and lower Yangtze River between Yichang and Shanghai; this historical distribution has always been downstream of the site of the Three Gorges Dam project. Until the 1950s the species was also present in the Qiantang River.

Population Estimate

A series of surveys conducted between 1997 and 1999 provided a minimum population estimate of only 13 individuals. Although a number of unverifiable opportunistic sightings have been reported by local fishermen over the past few years, a recent November-December 2006 international range-wide survey failed to find any surviving animals in the Yangtze, and it is likely that the species is now extinct.

Population Trend

Survey results indicate that numbers have declined rapidly and continuously over the past 30 years, from an estimated 400 animals in 1980 to only 100 animals in 1990. The population decrease has been estimated to be roughly 10% per annum.

Status

The baiji is classified as Critically Endangered (CR C2a(ii); D) on the 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. If it still survives, it is the world’s rarest and most threatened cetacean species.

Threats

The main threats to the survival of the species are from the massive human impacts on the degraded Yangtze ecosystem. Over 400 million people live within the Yangtze River catchment, and the riverbanks are lined with large, industrialised cities. The river is one of the world’s busiest waterways, and is heavily utilised for transport, fishing and industrial development. Probably the major cause of mortality is accidental by-catch from gill-nets, and illegal rolling hook lines and electro-fishing (which were both banned two decades ago in China because they kill dolphins, but which are still widely used along the Yangtze). Other deaths have resulted from collisions with boats, and engineering explosions for maintaining navigation channels. The Yangtze’s environment has been further degraded by pollution, upstream damming and dredging. In particular, the recently completed Three Gorges Dam is likely to affect downstream fish stocks and further reduce areas of suitable habitat. Population fragmentation is also likely to have affected any surviving baiji individuals.

Conservation Underway

The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and regional Yangtze authorities have imposed restrictions on harmful fishing and waste discharge in the river, and have officially designated a series of baiji reserves in the main Yangtze channel between Honghu and Zhejiang. However, there has been little effort to enforce these conservation measures, and there is no apparent difference between levels of legal and illegal fishing in the baiji reserves and in the remainder of the river. Despite being listed on Appendix I of CITES and having been a protected species in China since 1975, surveys carried out over the past twenty years have indicated a continuous decline in population size.

Conservation Proposed

More drastic conservation measures have been advocated since the mid 1980s, and Chinese and international scientists and policy makers have consistently recommended the removal and translocation of baiji from the Yangtze to a safer environment, to establish a closely monitored ex situ breeding programme under semi-natural conditions. This strategy has also been recommended at a series of international conservation workshops held in China and abroad over the past two decades. The initial site suggested for this breeding population was the Tongling semi-natural reserve in Anhui Province, but most recent attention has focused on the Tian'e-Zhou semi-natural reserve near Shishou City in Hubei Province, a 21 km oxbow which used to be part of the main Yangtze channel until 1972. Chinese authorities are also keen to establish a baiji population in the Wuhan dolphinarium, which now supports a breeding population of Yangtze finless porpoises.

Unfortunately, despite the apparent commitment expressed to the species by several major conservation organisations, almost no funds have ever been provided by the international community to initiate any active conservation action for the species. The only active efforts to establish an ex situ population were conducted in 1995, when a Chinese team translocated a single baiji to Tian'e-Zhou. Sadly this animal died a few months after being released in the reserve. As the baiji may now be extinct, the only remaining conservation option is to conduct a wide-range series of interviews with fishermen along the Yangtze, to try and ascertain whether any baiji still survive in the river.

www.edgeofexistence.org/species/species_info.asp?id=1