|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 2, 2005 21:44:47 GMT

also moved ... it is stuffed, it has a specimen-note or -paper on its leg and it is mounted on a shelf. The colours are not that good because this is a giv. picture. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 2, 2005 21:45:27 GMT

also moved I know, but in the site, it is said, I think, that it is a juvenile. So, maybe the colours are not so bright because of it... |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Nov 6, 2005 21:03:41 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 7, 2005 7:01:35 GMT

gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by Bowhead Whale on Nov 9, 2005 18:06:23 GMT

Thank you for creating a page about the pink-headed duck. Peter, I told you I had interesting things to bring to this forum!

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 9, 2005 18:35:27 GMT

Thank you for creating a page about the pink-headed duck. Peter, I told you I had interesting things to bring to this forum! its my pleasure another specialist - i started this thread |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Nov 13, 2005 9:51:34 GMT

Yes Bowhead Whale you did! I enjoy reading your posts. The Pink-headed Duck might indeed still survive. Currently they are doing surveys in order to rediscover it. And there is a high chanche the will succeed!  ;D |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 13, 2005 18:17:49 GMT

Conservation Action by WWT In 1998, WWT supported an expedition to Tibet by Peter Gladstone and Charles Martell from the UK. Tibetan Government Forestry Department staff had reported Pink-headed Ducks surviving in a remote region to the north of Bhutan, but the expedition did not locate any birds. The findings of two expeditions to Myanmar in winter 1999/2000 are eagerly awaited. |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:13:18 GMT

The Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea ( Latham, 1790) once lived in inaccessible swamps of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers in northern India. It has always been considered rare, but this may have been due to the inaccessibility of its habitat. As the swamps became cultivated, this handsome duck was initially seen more frequently. However, reclamation of the swamps inevitably led to the decline of the species in the beginning of the 20th century. Its remarkable appearance made it a favoured hunting trophy, though this is probably not the main cause of its extinction. The British who governed the area found its meat far from tasty. The fast-growing local population may, however, have had a different opinion. Pink-headed Duck. The last specimen died far from home As to the exact date of extinction, opinions vary from 1936 or 1939 to 1945. Most likely, the last Pink-headed Duck died far from its native swamps, in a British aviary. During the 1960's its presence was claimed near the Burmese-Tibetan border, but this may be based on misidentified Red-crested Pochards Netta rufina. In any case, the claim has not been substantiated. Pink-headed Duck. Photograph by Rosamond Purcell from Swift as a Shadow. © 1999. The museum collection The National Museum of Natural History possesses one male from India. Collector and collecting date are not known. Over 70 skins are preserved worldwide. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- two photos www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/ |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:15:24 GMT

PINK-HEADED DUCK

Rhodonessa caryophyllacea

Critical D1

Endangered —

Vulnerable —

This duck is probably extinct, but until the last known areas of its former range are surveyed this cannot be confirmed. Any remaining population is likely to be tiny. It therefore qualifies as Critical.

Distribution The Pink-headed Duck (see Remarks 1) is a remarkable, mysterious and, sadly, almost certainly extinct species, the majority of records of which are from India, with a much smaller number from Myanmar and a handful from Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal. Although stragglers have been recorded in the Punjab and southern India, most records are from India's north-eastern states and northern Mynamar. Hume (1879c) judged that the species was generally confined to the east of 80°E, and Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) adduced its normal range as follows: Bihar and the rest of "Bengal" north of the Ganges and west of the Brahmaputra as the core, with the Nepal and Oudh terai, central and eastern Oudh (= Avadh), "Varanasi division" of "North-Western Provinces" (presumably western Uttar Pradesh and eaternmost Bihar), whole of the rest of Bengal, Assam and Manipur, and the eastern littoral as far south as Madras, as the region within which it was at least seasonal, albeit in many places rare (records beyond these areas being entirely exceptional).

However, Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) inferred that the Pink-headed Duck "may extend via Assam and Upper Burma into south-western China (Yunan)"; but there remains no evidence to support this.

Two specimens in BMNH are labelled from "Bootan" and were catalogued before 1844 (Salvadori 1895); it is likely that the area involved was Assam adjacent to present-day Bhutan, not Bhutan itself (the former usage of "Bootan" extended to a larger area than today, including lower-lying areas and wetlands such as the duck would have inhabited—there are virtually no lowland wetland areas in modern Bhutan: T. P. Inskipp verbally 2000). These ancient specimens also constitute the records attributed by Baker (1908) to "Pemberton" in Tibet. Otherwise, the notion that the species might be found in Tibet appears also to stem from a correspondent (U Tun Yin) in Kear and Williams (1978) who, having passed on a (highly improbable) record of the species from some rapids in Myanmar, reported it as regular in winter in northern Myanmar and possibly surviving "in the Land of Jove area of Tibet". This idea and/or the report in Baker (1908) led to an expedition to search for the species in Tibet but (predictably, based on the data assembled under Habitat) no trace of it was found there (C. Martell in litt. 2000).

Meanwhile, erroneous reports of the species litter the recent literature; for example, Rana (1988) stated that it often visits the semi-arid zones of western Rajasthan.

• India The Pink-headed Duck was once recorded throughout northern India, with the epicentre of records in "Bengal", a jurisdiction which is (within India) currently subdivided into Bihar, Orissa and western Assam (Ali 1960), but which also covered Bangladesh. When Hume (1879c) dismissed Jerdon's (1862_1864) claim that it was "found at times throughout Northern India" with the phrase "nothing can be more misleading", he was reflecting his own frustration at obtaining so few reports of the species, which already by that time had evidently become extremely patchy.

An important testimony is provided in a retrospective article by Simson (1884), who, while indicating that the species generally frequented areas north of the Ganges and west of the Brahmaputra, judged that its centre of abundance was "in a restricted area of Bengal", such that it "may be said to make its home in the southern part of the district of Purneah, and in the country which borders the left or northern bank of the Ganges, between the Coosy River [now the Kosi or Ghuari river], which separates Purneah from Bhangulpore, and in the Maldah district"; he considered it to occur "more sparingly" in Bhagalpur and Tirhut, and specifically noted its absence from the foot of the Himalayas north of Purnea. Jerdon (1862_1864), who evidently adjusted his account of the species to fit what Simson (1884) had long before told and shown him, declared it to be "most common in parts of Bengal... [but] rare in the N. W. Provinces, and still more so in Central and Southern India", with specimens rarely taken as far south as Madras and with evidence of occasional visits to the Deccan. Baker (1908) thus described its range as Orissa, as far south as Madras and all through eastern Bengal and Assam up to Manipur.

The records are from:

• Punjab Keshopur jheel, Gurdaspur, one of three birds shot, September 1917 (Marshall 1918), this clearly being the undated record from Gurdaspur in Baker (1922_1930); Rupar (Ropar), on the Sutlej river, Ambala district, March 1916 (Whistler 1916b; hence Baker 1922_1930, Ali and Ripley 1968_1998; see end of Habitat);

• Delhi banks of the canal feeding Najafgarh lake (Najjafgarh jheel) near Delhi, three birds in 1862_1863 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Bucknill 1924a, Abdulali and Pandey 1978; see Remarks 2);

• Uttar Pradesh Palia, north of Kheri district, 1921 (specimen in BMNH, Abdulali 1968_1996; also J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 27 [1921]: 971); Shahjahanpur district, one bird killed and eaten, 1922 (Bucknill 1924a), February 1923 (Wright and Dewar 1925); Koosumba Tal, c.40 km north of Kheri, a "very large number", May 1883 (Tweedie 1887), including Kheri district and north Kheri district, near the southern border of Nepal, in sal forests in the 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881), 1921 (Bucknill 1924a), 1924 (specimen in USNM); Gondah or Gonda district, regular cold-weather visitor, 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); near Rahimabad, two birds, December 1878 (Reid 1879, 1887); Lucknow, from time to time, 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881), several birds collected before 1924 (Bucknill 1924a; also Stray Feathers 8 [1879]: 418), these including two in A. O. Hume's possession (Stray Feathers 7 [1879]: 528 footnote), one certainly from near Lucknow (Hume 1879c), which was at that time the administrative centre of "Oudh" (Avadh), a large region designated as the type locality of the species, where it was apparently encountered only as an uncommon migrant ("three times seen towards the end of the rainy season—twice in small flocks of seven or eight, and a single bird") (Irby 1861, Hume 1879c), with a few birds seen, shot or netted each year before 1896 (Baker 1908) and one shot in the north in 1922 (Bucknill 1924a); Basti (Bustee, Busti), 1870s (Hume 1879c, Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); Gorakhpur (Goruckpoor), 1870s (Hume 1879c, Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); near Mohanlalganj (Mohunlalgunj), on the Rai Bareilly road in the cold season, pre-1880 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881, Reid 1887); Fatehpur, pre-1879 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Bucknill 1924a), and in Faizabad district generally (including Fatehpur), regular cold-weather visitor, 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881);

• Madhya Pradesh Depalpur (Depalpore lake), undated (Swinhoe and Barnes 1885, also Barnes 1885; see Remarks 3); Mhow, undated (Barnes 1885), this presumably being the pre-1921 record mentioned by Bucknill (1924a);

• Maharashtra Jalna, as a reported straggler, before 1878 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Ali and Ripley 1968_1998); as far west as Ahmednagar (Ahmadnagar), once (Fairbank 1876, Hume 1879c, Bucknill 1924a; see Remarks 4);

• Andhra Pradesh lake near Kondakarla (Condakirla), 44 km south of Vishakhapatnam (Vizagapatam), 15 or 20 birds on each visit, probably all in November and December, pre-1879 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); about 30 km from Secunderabad, "after the rains had set in", pre-1868 (Vagrant [alias of McMaster] 1868; also Hume 1879c, Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); Nellore, c.1840s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881);

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:15:42 GMT

Tamil Nadu Pulicat lake, 1871 (Hume 1879c, Hume and Marshall 1879_1881, Bucknill 1924a), plus a specimen bought by T. C. Jerdon in Madras market (c.1840s) which was purportedly caught at Pulicat lake (Hume 1879c, Hume and Marshall 1879_1881);

• Bihar Dumra, at an indigo factory tank near Sitamahri (Sitamarhi), male and female, 1898 (Bucknill 1924a), with a general record of its occurrence in Tirhut in the 1880s by Simson (1884); Tetaria (Tatariah), c.1930, two shot (Inglis 1940_1946); Benoa chaur, Madhubani subdivision, Darbhanga district, a male collected from two birds, August 1903, and another individual, June 1905 (Inglis 1901_1904, 1940_1946); Patraha katal (or jheel), apparently 11 km west of Forbesganj (see Remarks 5), female in distraction display, July 1880 (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Baker 1908, Ali 1960); Darbhanga, 1903 (specimen in BNHS, Abdulali 1968_1996), and either 7 March or 3 July 1923 (two specimens in YPM, collected by C. M. Inglis and dated "03/07/1923"—unless 1923 is a mistranscription of 1903), and at Minti (untraced), Darbhanga district, one snared, before 1901 (Inglis 1901_1904) and Baghownie, July 1910 (Inglis 1940_1946, specimen in NRM), August 1910 (specimen in BMNH), June 1935 (Inglis 1940_1946; hence Ripley 1952b, Ali 1960) and, at nearby Simarda, April 1923 (Inglis 1940_1946; specimen in YPM); Muzaffarpur district (Mozufferpore), before 1896 (Baker 1908), 1898 (Inglis 1940_1946); Bhamo factory, Saran district, one male, October 1899 (Bucknill 1924a, Inglis 1940_1946); Purnea (Purneah, Purnia), c.1867 (juvenile in BMNH), southern part, in one case on or near the Kolassy plantation (Simson 1884), central or higher parts of the district, before 1896 (Baker 1908), five birds, February and June 1880 (Baker 1897_1903), and Zillah, Purnea, egg taken in 1891 (Walters 1998a); Patna, on the Ganges, two birds, summer of an unspecified year (E. A. D'Abreu in Whistler ms); Bhojpur jheel, near the Dumraon railway station, Arrah district, November 1879 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Baker 1908); Dabeepoor factory (Debeepoor indigo factory), Purnea, July 1880 (four eggs in BMNH, as referred to in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; see Breeding); near Karagola, 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); Bhagalpur (Bhangulpore), in parts of the district immediately north of the Ganges and adjacent to south-west Malda district, pre-1884 (Simson 1884; hence Baker 1908); Sahibgunj (Sahibganj), on the Ganges, pre-1874 (Ball 1874); Monghyr district, Bakhtiarpur, March 1924 (editorial footnote to Ara 1960; photograph in J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 63 [1966]: opposite p.441), and Furekeer, July 1905 (Inglis 1940_1946), this presumably being the undated record of a skin from Monghyr (Munger) (E. A. D'Abreu in Whistler ms), and Manroopa lake, Khagaria subdivision, (since 1965 Bhagalpur district), one shot in January 1947 and 5_8 seen in 1948_1949 (Singh 1967; see Remarks 6); Bhoonda jheel, near Nawada factory, Nawada, Champaran district, 1898 (Bucknill 1924a, Inglis 1940_1946); Rajmahal hills (Rajmehal hills), 1869_1870 (Ball 1878); Hazaribagh (Hazaribah), 1860s or 1870s (Ball 1878); Ranchi district, Chota Nagpur, undated (Baker 1908); Sini, Singbhum district (Singhboom district, Dhalbhum district), six birds, undated, and frequently met with in various parts of the district, undated (Baker 1908); near Barauni (not mapped), specimen reportedly shot, 1948 (Mukherjee 1974);

• Orissa Khordha (Khorda, Khurda), including Kalapathar patna (Kalapathar), near Mahanadi river, where shot for sport and locally reported as breeding (but unquestionably rare), in the period 1870_1886 (Taylor 1887; also Bucknill 1924a); Ganjam, undated (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881);

• West Bengal Maldah (Malda), four or five shot, late 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881, also Baker 1908), June "1879" = 1898 (Baker 1932_1935; see Remarks 7), 1925 (egg in BMNH); Krishnanagar (the best candidate in view of the fact that the untraced "Kishnaghur" was near Jessore in Bangladesh), "years" before around 1878 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881); Manbhum, Chota Nagpur (formerly in Bihar, now part of Puruliya district [Purulia]), sight records believed to be reliable, undated (Ball 1874; see Remarks 8), and (possibly the same records) specifically at Puruliya, pre-1896 (Baker 1908); Chhora jheel (c.80 km east of Asansol), near Galsi, Burdwan district, near the Ajai river, 1939_1940 (J. Jameson 1969; see Remarks 9); Howrah, near Calcutta, winter, pre-1900 (Bucknill 1924a), with several records of birds sold in Calcutta market, 1843_1847 (Blyth 1849_1852) and subsequently, the birds sold there all probably having been hunted within a 40 km radius of the city (Hume 1879c);

• Assam (see Population) Sadiya, undated (Hume (1888); Goalpara district, by report as the source of captive birds exported to London, 1920s (Delacour 1954_1964, Ali 1960); Nowgong, flocks of several birds, March of the years 1921_1923 (Higgins 1933_1934); by repute from Dhubri, in the early 1930s (two specimens in USNM, YPM);

• Manipur 15 km south of Imphal, Manipur basin, one shot of a presumed breeding pair, June 1932 (Higgins 1933_1934), and Senaput, c.16 km south-west of Imphal, one of a pair shot, October 1910 (Higgins 1913a); Logtak lake (north-east corner), two birds shot from a small flock, pre-1881 (Hume 1888), and at an unspecified locality in the Manipur valley (Manipur basin), one bird shot, November 1908 (Higgins 1933_1934).

A report of a pair on the Belsiri river in the Balipara Frontier Tract in Assam, 1937, was mentioned but rightly treated with suspicion by Ripley (1950a). Another, involving a single bird in a tank in "Kunihar State", c.55 km south of Simla, in February 1960 (Mehta 1960), was shown to be have been based on torchlight observations (J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 59 [1962]: 626), and is thus unacceptable.

• Nepal There is a single specific record from the Kathmandu valley, September, pre-1829 (Hodgson 1829a, 1844), with a report from the Nepal terai, apparently resident, 1870s (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881).

• Bangladesh Rashid (1967) listed the species as possibly occurring in the north-eastern region or the south-central region of the country, while Khan (1982) pronounced it nationally extinct. Records are from: near the confluence of Tista river and Brahmaputra river, specimen(s) collected, c.1930 (Ripley 1952b, Delacour 1954_1964); Sylhet, undated (Hume 1888); Dhaka (Dacca), winter, pre-1900 (Bucknill 1924a); Faridpur, winter, pre-1900 (Bucknill (1924a); Jessore, "years" before 1878 (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881), in 1878 (one male in MNHN), and in winter, pre-1900 (Bucknill 1924a), January 1924 (Bucknill 1924b); Benapol (jheel near the railway station), party of 5_6, 1923 (Bucknill 1924b); eastern Rangpur district by report as the source of captive birds exported to London, 1920s (Delacour 1954_1964).

• Myanmar The species has only been recorded from a few localities, with the last confirmed record dating from 1910 (contra 1908 in Smythies 1986). A report (by U Tun Yin) of five birds in rapids on the Mali Hka river, near Machanbaw in Kachin state close to the Tibetan border, in 1965_1966 (Kear and Williams 1978) fails to conform with almost all the evidence to date that the species never utilised rivers (see Habitat). Records are from: Myitkyina, undated (Harington 1909a), also near Talawgyi village, not far from Myitkyina, where two birds resembling illustrations and never previously seen were present in winter 1998/1999 (U Tun Yin—a local hunter, not the person above—per U Nay Myo Shwe per SC); Bhamo, undated (Blyth 1875, Smythies 1986); Koolay, near Singu, Mandalay district, one female, December 1908 (specimen in BNHS, Jardine 1909); in the Mandalay region, four reportedly shot, undated (Jardine 1909), and presumably nearby, February 1910 (one male acquired from Mandalay bazaar in AMNH); Arakan, undated (Blyth 1875, Smythies 1986).

Population Accounts of the abundance of the Pink-headed Duck by people who knew it at first hand are variable. Blyth (1849_1852), noting it as present in "India generally", called it "not common in L. [Lower] Bengal", while Jerdon (1862_1864) described it as "most common in parts of Bengal" (see Remarks 10). Inquiries made by Hume (1879c), in an attempt to discover its centre of abundance, revealed that it was rare everywhere he asked ("the Howrah, Jessore, Dacca, Furreedpoor, Sylhet districts", hence "either absolutely wanting or uncommon in every part of India"; also "scarce in Upper Burma"); E. A. Butler (1881) likewise reported that it "seems to be rare everywhere". Simson (1884) indicated that the centre of abundance was in southern Purnea district, Bihar, and described occasions, evidently in the 1860s, when he had seen loose flocks of up to 12 birds; he generalised this as being "found in small flocks of from eight to twelve", which he considered probably family parties of the year. This testimony is independently supported by correspondents (notably F. A. Shillingford) of Hume and Marshall (1879_1881), who identified the neighbourhood of Karagola in southern Purnea as the area in which the duck was "specially abundant", Shillingford himself (quoted in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) reporting the species "in considerable numbers" in south-west Purnea, eastern Bhagalpur north of the Ganges, and south-west Maldah. Jerdon (1862_1864) referred to its general occurrence in the cold season in "parties of from four to eight", but occasionally "in flocks of twenty or so". Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) described it as occurring in small parties of 4_8(_10) in the cold season, sometimes 20_30, but in pairs in the breeding season.

By the mid-twentieth century Ripley (1950a) was inclined to treat the species as extinct, and several efforts at rediscovering it failed (Ali 1960). The view that it is most likely to be extinct is based on the consideration that "from the hundreds of sportsmen who regularly shoot ducks in north-eastern India, in the known habitat of the species", there had not been a single report of a Pink-headed Duck, nor had one ever turned up amongst "the tens of thousands of ducks shot every winter… or even in the Calcutta bird market where up to half a dozen or so live birds could be seen in most winters in the 1890s and up to the first decade of the present century" (Ali 1960). Moreover, in the 30 years up to around 1960, a "highly tempting monetary reward" had been offered for a specimen but was never claimed (Ali 1960). Efforts to obtain information from old shikaris in northern Bihar in 1964 were equally fruitless (George 1964).

While it seems entirely probable that the species is indeed extinct, there remains the slight possibility that a population might survive in a remote area. It has been beyond the scope of this review to identify where such areas might exist, since this would require such things as matching distributional data on the species with those on human land use and population densities, but such exercises may conceivably result in the perception that a particular area north of the Ganges, in the Brahmaputra valley, or in northern Myanmar has been (a) little affected by human activity in the past 50 years and (b) neglected by ornithologists, thus meriting urgent investigation.

India Jerdon (1862_1864) described the Pink-headed Duck as commonest in parts of "Bengal" but found at times throughout northern India, rarely in the north-western provinces, and still more rarely in the central and southern parts. In 1880 an anonymous writer (apparently F. A. Shillingford) again identified "Bengal" as the headquarters of the species (Ali 1960). Clearly commonness and rarity are dependent on several elements—spatial, seasonal, temporal, perceptual and conceptual—and the following two paragraphs treat the two valuations in turn.

Evidence that it was common Jerdon (1862_1864) suggested that the species might have been locally quite common. Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) cited J. Battie that it was "not very uncommon" in the north of the Kheri district in Oudh. On the evidence assembled in the 1870s, it was judged "comparatively common" in Tirhut and Purnea (see Remarks 11), but throughout the rest of "Lower and Eastern Bengal", and in Sylhet "and the entire valley of Assam up to Sadiya" it was rare (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881). According to Baker (1922_1930) birds were formerly "not rare in parts of Eastern Bengal and sometimes half a dozen could be picked up when returning from a tiger shoot". In Lucknow (Oudh), the species was characterised as common soon after it was described for science (see Baker 1908, Ali 1960). Tweedie (1887) reported a large number in a reedy pool in Bihar, and Ball (1874) thought it "not uncommon in the proper season" near Sahibgunj on the Ganges. Blanford (1895_1898), evidently depending on the testimony in Hume and Marshall (1879_1881), described it as a fairly common resident in Upper Bengal (i.e. mostly Bihar), in the districts of Purnea, Malda (south-west portions), Bhagalpur (immediately north of the Ganges) and Tirhut; F. A. Shillingford (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) reported that flocks of 6_30, and sometimes even 40 birds, could be found in winter. It was apparently very frequent in various parts of Singhbhum (Baker 1908). At Puruliya, West Bengal, it was fairly common before 1896 (Baker 1908), and was common in Malda, Puruliya and adjoining districts, with the first two places most preferred (Baker 1908). Swinhoe and Barnes (1885) reported it "very plentiful in Lake Depalpore during the winter months", although the identification was later questioned chiefly because no other records existed for the Bombay Presidency (Barnes 1888_1891).

Evidence that it was rare Since being described in the 1790s the species was probably always scarce (Ali 1960). Although others claimed that it commonly came up for sale in the Calcutta market, Hume (1879a) encountered it only five times there over a six-year period, and felt that by that time, except for Goruckpoor and Bustee, it occurred nowhere in northern India (i.e. North-West Provinces, Punjab, Rajpootana, Sindh, Central India or Bombay) and in Oudh only as a rather uncommon migrant. Tweedie (1879) remarked that, in five years' hunting around Kheri, he never came across this species, and that he had never found it around Oudh. Such evidence probably influenced E. A. Butler's (1881) view that the species was rare everywhere, and Baker's (1908) that it was very rare in north-western (i.e. lowland western) India. Although it appeared in small numbers "at one season" in the southern part of Purnea district, Hume (1879c) commented that "there is something odd about this duck. It must be common somewhere, but where, I have failed to discover". Taylor (1887) judged it rare in Khorda, Orissa, and Reid (1887) found it "exceedingly rare" in the Lucknow subdivision (which now includes Unnao, Lucknow and Barabanki districts), although he was told it was more frequent during the rains. Thus after another decade of reports and enquiries, Hume (1888) could only call it "excessively rare", "very scarce" and little more than an occasional straggler in the north-eastern states of Assam, Manipur and Sylhet, and not recorded in Cachar. It certainly appears to have penetrated parts of Assam, as Higgins (1933_1934) commented on the fact that he thought it bred further east than was normally assumed, and Milroy (1934) remarked that the Pink-head was "the most interesting bird that Assam can boast of", recording that "there were a good few at one time in some lagoons" but that hunting and habitat clearance now meant that "the last of the duck is likely to disappear".

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:16:03 GMT

In the 1920s Baker (1922_1930), who perhaps overstressed the use of forest by the species (see Habitat), believed that, although perhaps driven by cultivation from some of its former haunts, it would "probably still exist in some numbers" in "remoter and less trodden jungles". Inasmuch as in the year this opinion was published 10 birds were imported into Europe, supposedly coming from Goalpara and eastern Rangpur, it is possible that Baker was correct. The comment had built on a note he had sent to Phillips (1922_1926) in which he demurred from Finn's (1915) view that absolute protection was now essential for the species:

"It is so seldom seen and so little known because it inhabits only the wildest country, the haunts of tigers and other animals that the native keeps as far away from as he can, whilst its malaria-stricken tracts are avoided by both white and black men during the breeding season. Forty years have elapsed since I first saw it and no reward has sufficed since then to induce `shikaris' to visit its breeding places and find me a nest and eggs. As civilization and cultivation advance the bird may be driven back, but it will be many generations before it can be affected thereby."

Bucknill (1924a) expressed a similar view, but much more tentatively—"it is possible that there are some few birds still to be found on remote and seldom-visited jheels"—and he countered this idea with the following: "but the fact, that out of hundreds of thousands of Duck brought to bag in the last twenty years in the Bhagalpur and other neighbouring districts, less than a couple of dozen specimens of this indigenous Duck have apparently been noticed seems to indicate its present rarity." Certainly by the 1930s Baker's optimism was lost on Whistler and Kinnear (1931_1937), who remarked that the species was "now so dwindling in numbers that the chance of its occurring again in the [Madras] Presidency is of the very slightest". Fooks (1947), however, reported, in a remarkably offhand manner, that there were "still quite a number about in the Purneah district though their numbers must be rapidly dwindling owing to continual trapping by the locals". This appears to have been the last general assessment of its numbers anywhere.

Nepal According to Baker (1908) the species was obtained from B. H. Hodgson more than once in Nepal, but was probably rare there.

Bangladesh Although some nineteenth-century status assessments concerning "Bengal" (see under India) would have included western Bangladesh (and hence have suggested that the species might have been moderately common there in the past), it was considered "excessively rare" in Sylhet (Hume 1888).

Myanmar It was apparently always rare in the country (Harington 1909a), although E. W. Oates (in Jardine 1909) reported four shot near Mandalay, suggesting that it might have been regular in the area. Although the last confirmed report was in 1910, there are recurrent rumours of its continued survival in the remote wetlands of the north (Scott 1989). Unconfirmed sightings of small numbers (4_5 birds) were reported in the late 1960s (U Tun Yin in litt. to W. B. King in BirdLife files; also Kear and Williams 1978), providing a slim hope that the species might survive. A recent report from near Myitkyina (see Distribution) must be considered highly improbable but worthy of follow-up.

Ecology Habitat The Pink-headed Duck was characterised by Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) as a lake and swamp species, affecting "tanks and pools, thickly set with reeds and aquatic plants, swamps dense with beds of bulrushes and the like, and nullahs and ponds hemmed in by forest"; it was never found on rivers or running water of any kind, a point confirmed by B. H. Hodgson (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881), who also indicated that it was strictly a lowland species. Since this careful assessment was made, nothing concrete has emerged to contradict it; the bird's association with rivers clearly only involved areas flooded by rivers, not the rivers themselves (see Remarks 12). From the evidence under Migration, the ecology of the species was closely related to wet-season flooding, which presumably produced flushes of aquatic life in clear-water pools.

The region judged to be the Pink-headed Duck's centre of abundance is alluvial, and in the 1880s consisted of "vast, extensive, and much-neglected plains, studded at considerable intervals with small poor villages, intersected with very deep clear streams", terrain consequently "difficult to cross on foot in the dry season..., often inundated when the Ganges rises high", and moreover home to "scattered... pools of deep water, extending over areas of from ten to forty acres, abounding in wild fowl and crocodiles, surrounded by very high grass... and covered with beautiful lotus plants" (Simson 1884). On these pools "the Pink-headed Duck resorts at all seasons of the year" (Simson 1884). One correspondent (J. Battie) reported that the species was often seen "in pairs in nullahs in the forests" (sal forests) in Kheri district (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881). F. A. Shillingford (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) reported its cold-season presence in "large swamps fringed with dense jungle" and "lagoons adjoining the large rivers". This testimony presumably lies behind the references to its "decided preference for tanks and jheels well sheltered by overhanging bushes, or abounding in dense reeds" (Jerdon 1862_1864), small secluded pools surrounded by tall grass and forest (Baker 1908, Ali and Ripley 1968_1998), "thick, weedy, reed-covered tanks lying just outside the heavy forest" at Sini (Baker 1908), and, in winter, lagoons adjoining large rivers (Ali 1960).

Baker's (1932_1935) conclusion that it "breeds in the densest forest" appears, on the basis of the foregoing, to be too strong, although he also noted its breeding in "Ekra and Elephant grass". Tweedie (1887) found it in a tank at the edge of a forest with a deep fringe of grass all round. W. J. Wilson in Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) reported that along India's east coast north of Nellore it occurred in lakes (in some way "peculiar to the Circars") that were "extensive and thickly covered by aquatic plants, so that the birds have plenty of cover". Shikaris of a friend of Bucknill (1924b) reported that the birds appeared "at the beginning of the rainy season... in the most secluded and reed-surrounded small jheels". A flock at Logtak lake in Manipur kept to a "weedy lagoon" (Hume 1888).

It appears to have been a relatively solitary species, occurring in pairs in the breeding season or small groups in winter, not usually joining the large wintering concentrations of migrant waterfowl (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881). Its retiring nature is conveyed by Baker's (1908) report of birds sometimes being shot late in the day, "getting up in front of the line of elephants as they worked through country in which there were any small ponds and jhils"; his later report that it was recorded in the company of a large number of other waterfowl, principally other ducks and teals (Baker 1908), therefore rings false as a generalisation. Although it was observed in parties of up to 40 (Jardine 1909), and a pair was seen in the company of Spot-billed Ducks Anas poecilorhyncha (Higgins 1913a), the species was often more solitary, occurring most frequently as individuals or pairs, at least at certain times of year (presumably the breeding season) (J. Latham in Baker 1908). Simson (1884) never saw it in association with other duck species or in large flocks.

Whether it settled in trees is not certain. The fact that perching was reportedly never observed (Humphrey and Ripley 1962) may have been based on Finn's (1923) description of it as "not a percher". However, Ali and Ripley (1968_1998) asserted that it sometimes perched in trees, without indicating a source. Delacour (1954_1964) actually kept them, and therefore his comment that "they never perch nor dive in ordinary circumstances, and behave much like Dabbling Ducks in a general way" can be assumed to be based on his personal authority, albeit of birds in confined circumstances.

Food The Pink-headed Duck was both a surface feeder and a diver (Finn 1909, 1915, Ali and Ripley 1968_1998), a captive individual being observed once (apparently, however, in "fun") to dive "just as neatly as a Pochard, and... as long", but otherwise exhibiting the behaviour of a "true surface-feeder" (Finn 1901a, 1915; see Remarks 1). The scant evidence suggests that the species consumed both plant and animal matter. "Half-digested water weeds and various kinds of small shells" were found in the gizzard of a specimen (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Baker 1908, Ali and Ripley 1968_1998). In the stomachs of a pair collected in April were the remains of small shellfish, a small crab and some shells (Wright and Dewar 1925, Inglis 1940_1946). Simson (1884) described the species as keeping "rather to itself", adding that it was "seldom... seen flying to the feeding-ground before sunset, but stays all day in the pools, where it lives till disturbed." This passage suggests that the species relocated for night feeding, although B. H. Hodgson (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) appears to have been the only observer to have indicated that it "feeds at night". The fact that the flight of the species was specifically reported to be "very powerful and rapid" (J. C. Parker in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) suggests some strong dispersive capability perhaps on a daily basis. Jerdon (1862_1864) reported that "during the heat of the day, it generally remains near the middle of the tank or jheel".

Breeding In "Bengal" the species apparently bred between April and October: arrival in the breeding areas of central Purnea was noted in April, nest-building in May, eggs (5_10) in June_July, and fledging of young and departure in September_October (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Baker 1908, Ali 1960). That July was a laying month is confirmed by a record of a female snared in July 1910 which laid an egg in a basket during transportation to its future owner (C. M. Inglis in Bucknill 1924a, Inglis 1940_1946). F. A. Shillingford (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881) described the species as living in small parties from November to April, and in pairs from June to September. Jerdon (1862_1864) stated that it bred "towards the end of the hot season... its eggs... laid among thick grass not far from the water". One nest (at Dabeepoor factory; see Distribution) held nine eggs and was 23 cm wide, 10_12 cm deep and circular; it was made of dry grass interspersed with a few feathers, and well hidden in tall grass Andropogon muricatum about 400 m from a nullah containing water (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881, Baker 1908; hence Wright and Dewar 1925, Baker 1932_1935, Ali 1960). This was later generalised as nests being placed in the centre of grass tufts less than 500 m from water (Hume and Oates 1889_1890, Baker 1908, Ali 1960). Simson (1884) reported that the species nested "in short grass on dry land at some distance from the pools" on which it was otherwise found throughout the year, which concurs exactly with Shillingford's testimony (but may have been repeating it). Reported clutches were between five and ten eggs (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Hume and Oates 1889_1890, Baker 1908, Wright and Dewar 1925, Ali 1960). Clutches were said to contain six or seven eggs (Barnes 1888_1891) or five to ten eggs (Murray 1889). Based on their continuous loss of body weight in the nesting season, males were thought very likely to contribute to incubation and parental duties during the breeding season, and were certainly sometimes flushed, with females, near nests (F. A. Shillingford in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; hence Baker 1908). Although it was at one time not uncommon in the collections of European aviculturists, the species never bred in captivity (Ezra 1925, Delacour 1954_1964, Humphrey and Ripley 1962). Once young were fledged in September, birds apparently moved with the receding waters to jungle lagoons (Baker 1908, Ali 1960).

Migration While it appears to have been mainly non-migratory, the Pink-headed Duck certainly undertook local movements (Ali and Ripley 1968_1998). In the Bihar, Purnea and Malda districts it was judged to be "a permanent resident", possibly also in the Nepal terai, and J. Battie reported that it was present all year in the Kheri district (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881). However, Hume (1879c) observed that it was "a migrant to a considerable degree" but that its movements were "confined apparently within the limits of the Empire"; he also (Hume 1879c) remarked that "in many parts of the country it seems only to appear during the rains". Thus F. A. Shillingford (in Hume and Marshall 1879_1881; see also Hume 1879c) mentioned finding the species year-round in Purnea, but in swamps adjoining major rivers in the cold season (November_April), and "generally in the higher parts only of the district" in the breeding season (basically the rest of the year); he elaborated this in an article cited by Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) as: "They come up to the central or higher parts of the Purneah district in pairs", and "retire with the receding waters to their usual haunts—the jungly lagoons". In Lucknow it was primarily a rare visitor during winter (Bucknill 1924a), although Reid (1887) called it "exceedingly rare" there during "cold weather" but, by local report, "more frequent... during the rains". It was presumed to be a rare cold-season straggler into the Punjab and Deccan (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881).

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:16:22 GMT

Threats This Pink-headed Duck was probably uncommon long before it was first discovered for science, and appears to have succumbed to a combination of habitat loss and hunting pressure.

Habitat loss It was "pushed back by increasing cultivation from places where it was once almost common", this referring to forest clearance ("cultivation has beaten back the jungle and driven the birds to yet remoter and less trodden jungles") more than wetland drainage (Baker 1922_1930). Bucknill (1924a) reported that "vast areas of swampy ground have been brought under cultivation within the last half-century", adding that human settlement of its haunts would have greatly increased the chances of its nests and eggs being found and taken. The phenomenal growth and spread of the human population in the bird's erstwhile habitats, and the consequent reclamation for cultivation of more and more of the swampy grass jungles inhabited by the species, appears to have contributed to its disappearance (Ali 1960). For example, breeding birds were present at Patraha in 1880 but by 1960 it was discovered that "all the chaurs and jheels have been reclaimed for cultivation" (Ara 1960). Similarly, Simson's (1884) favoured area, notably a traveller's bungalow on the Purnea Trunk Road, seems to have been at the intersection of the "Karhagola" Road in an area shown by an old map to be "full of jheels and chaurs" (the researcher being unaware of the remark by Shillingford that the Karagola area was one in which Pink-headed Duck were "specially plentiful"), but "unfortunately the bulk of this area too has been reclaimed for cultivation", and nobody could be found who knew the species (Ara 1960).

Hunting It seems likely that hunting contributed to the decline and presumed extinction of the species. Early accounts of duck-hunting in its range are commonplace. Bucknill (1924a) thought that its sedentariness would have meant it was targeted year-round by hunters, and that the increase in "fowling-pieces" over the previous 40 years would have allowed it less and less respite. In marshes along the Brahmaputra, for example, Wilson (1924) reported four sportsmen shooting 1,400 ducks (not, of course, Pink-heads) in two-and-a-half days (140 ducks per gun per day, or about one bird every five minutes per person in a 12-hour day). In the nineteenth century, the species was regularly sold in the local markets of Calcutta and Lucknow (Reid 1887); Hume (1879c) stated that "daily hundreds, sometimes thousands, of wild birds, dead and alive, are brought to help fill the craving maw of India's Metropolis" at Calcutta market, and he noticed "a manifest falling off in the numbers of the migratory ducks" during the 1870s. As early as the 1850s the species was regarded as "excessively wary" in Oudh (Irby 1861), which may reflect a constitutive condition—Jerdon (1862_1864) also called it "somewhat shy and wary" and B. H. Hodgson, in Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) called it shy—or, more likely, an acquired response to hunting pressure. Against all this it has to be noted that the species was clearly highly restricted in range as early as around 1850, being only moderately abundant within a small area (as indicated by Simson 1884); moreover, it was in one person's view very poor eating (see Remarks 13).

Measures taken The species has been protected by Indian law against capture, killing or egg collection since 1956 (Ali 1960), and it is legally protected under the Wildlife Act (1994) in Myanmar. It is listed on Appendix I of CITES.

Throughout the 1950s there were minor attempts to establish clearer information on the status of the species, culminating in the important review of the literature and museum specimens by Ali (1960). Ara (1960) searched for it in some key areas (see Threats). Recent specific searches for the species have targeted northern Myanmar and southern Tibet in June 1998, but no suitable habitat was found in southern Tibet, the area being too mountainous and the forested regions too steep (C. Martell in litt. 2000). Some recently reported sightings were the result of confusion with Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina (Ripley 1952b, Choudhury 1995b). During surveys in Dibru-Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary, whose jungle pools were thought a possible refuge for the duck, illustrations were shown to villagers, but the few positive leads proved to refer to the Red-crested Pochard (Choudhury 1995b). In 1924 a pair of birds was shot at a site in Bihar/Orissa whose precise identity was suppressed by Bucknill (1924b) in order to increase its security from hunters. The site itself, a "very sporting estate", was then under direction to restrict shooting of the species (Bucknill 1924b).

Birds were kept in captivity in UK and France from 1925, and in the former facility "some lived over twelve years... displayed constantly... but none ever tried to nest" (Delacour 1954_1964). A record of where, when and in what numbers the species was held in captivity was compiled by Prestwich (1974); the last individual apparently survived until around 1945.

Measures proposed On the basis of the records compiled above, it is clear that the region bordering the north bank of the Ganges from opposite Bhagalpur down to the barrage at Farakka, and in particular the area around Karagola, represents what was, 150 years ago, the best and perhaps only major stronghold of the species. However, given the testimony of Bucknill (1924a), who "talked and shot with a number of well-known sportsmen [who] for the last twenty years or more regularly attended the big Duck shoots at Chapra, Bhagalpur, and other places on the northern side of the Ganges, and all of whom have always been on the look-out for rare specimens", but who "never met one who has shot, and only one—and he was the senior one of them all—who has ever seen a specimen in the flesh recently killed", it is wholly improbable that it could possibly have survived in those areas. It would, nevertheless, be of some interest to visit the region, review the state of the environment, and make inquiries of shikaris and old locals. Forty years ago Ara (1960) showed that some key areas in Bhagalpur and Purnea had been drastically altered, and there seems no serious chance that any habitat could today survive. Nevertheless, Singh (1962) reported meeting villagers in Purnea and surrounding districts in 1962 who believed that areas flooded annually by the Kosi river might still hold the species.

The two birds shot in 1924 at an undisclosed site (see Measures Taken) were placed with one Rowland Ward (Bucknill 1924b). They have not been found in any museum checked during this review of Asian birds, and it would be helpful to trace them now in case there is any accompanying documentation which identifies their provenance more exactly.

Remarks (1) Several studies (Johnsgard 1961, Woolfenden 1961, Humphrey and Ripley 1962, Brush 1976) have established that the closest relatives of the Pink-headed Duck are the pochards Aythyini. More recent phylogenetic analysis, and the species's apparent combination of dabbling and diving, have led recent authorities to extend the genus Rhodonessa to include the Red-headed Pochard Netta rufina (e.g. Livezey 1998, Robson 2000). However, the latter shows several characters linking it to Aythya, while the Pink-headed Duck shows several characters of its own—its basally deep (hence triangular) maxilla, pink coloration, long neck, somewhat anatine feet, weak sexual dimorphism (except in tracheal structure) and most especially its eggs (Hume and Marshall 1879_1881, Walters 1998a; also Garrod 1875). For these reasons the inclusion of rufina in Rhodonessa is rejected and the Pink-headed Duck remains generically unique. It is worth noting that Delacour (1954_1964), based on his personal experience, thought the species unlike any other duck "in proportions and colours"—he described it as having a "peculiar, if not very graceful shape"—and for this reason "quite remarkable". Finn (1901a) called it a "most extraordinary-looking bird". Ezra (1925) described the shape of the species as "one of a very slender and elegant Pochard", as witness to which see the photograph in Oiseau et R.F.O. 9 (1930), although in the long neck and head shape of several birds in that photo there is also a suggestion of a tree-duck Dendrocygna (NJC).

(2) Inglis (1896_1902) misrepresented the number of records from near Delhi as four; the fourth, recorded in Hume and Marshall (1879_1881), was inconclusive.

(3) The record from Depalpur lake should perhaps be treated with caution. Barnes (1888_1891) questioned it on the grounds of lack of corroborating evidence from elsewhere in the Bombay Presidency or by another observer at the site, but he admitted that the lake was "very strictly preserved, and very secluded, and... just the place suited to [the species]".

(4) The record as published by Fairbank (1876) indicated no specific locality— E. A. Butler (1881) and hence presumably Salvadori (1895) generalised it as "Khandala"—but, given the absence of tanks in two of four sites treated, it would appear that the observation was near either Belgaum or Ahmednagar (SS). Moreover, the fact that Hume (1879c) gave the record as from Ahmednagar suggests that he may have known more than had been published, and on this assumption Ahmednagar is used here as the site. It should be noted that E. A. Butler (1881) treated this record as provisional in the absence of a specimen.

(5) This site was searched for in the Bhagalpur area without success in 1960, but a place of this name was located on a map of Purnea, about 11 km west of Forbesganj (Ara 1960).

(6) An extended editorial comment on this record appeared to accept its validity ("We are therefore placing the present claim on record"), pointing out that Manroopa lake lies close to Bakhtiarpur, whence there was a record in 1924, and urging readers in the region to keep an eye out (J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 63 [1966]: 441). This thus becomes the last acceptable record from the wild.

(7) Baker (1922_1930) gave the year as 1878 and Baker (1932_1935) 1879, but Walters (1998a) gave 1898 and confirms (in litt. 2000) that "June 1898" is inscribed on the egg in question.

(8) Hume (1879c) reported Ball as having found the species at "Manbhoom and Chota Nagpore", although Ball reported it, on others' say-so, from Manbhum in Chota Nagpore. Hume and Marshall (1879_1881) referred to "Manbhum of Chota Nagpur". In any case the region was later part of Bihar but now falls within Puruliya district of West Bengal.

(9) J. Jameson (1969) gave the date as "1939/40", but his wife indicated 1939 (S. Jameson 1969). J. Jameson (1969) detailed the record as of a mallard-sized duck with a pink head and dark body, indicated his familiarity with and discounting of Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina, and considered his sighting "almost certainly" to have involved a Pink-headed Duck. It would seem unreasonable to regard this record as provisional, and it therefore becomes the penultimate acceptable one of the species in the wild (see Remarks 6).

(10) It is worth noting that Jerdon's comments appear to have been derived from information given him by Simson (1884), who described introducing the species to Jerdon in the 1860s in the Purnea area.

(11) Inglis (1901_1904) thought this "must be a mistake" as neither he, nor his fellow hunters, came across it in Darbhanga district; but, depending on whether he thought the comment on abundance was the mistake or the declared locality, it seems that it was Inglis who was mistaken.

(12) Baker (1908) reported it as an occasional visitor to open rivers in cold weather, but the basis for this is unclear. The pair seen by Whistler (1916b) on the Sutlej River, Punjab, were initially loafing on the edge of a river island, and when chased by a terrier settled either again on sandbanks or "in shoals"; this latter behaviour is certainly anomalous and might reflect one of three things: (a) a typical behaviour inadequately documented; (b) an atypical behaviour shown by possibly tired vagrants; (c) mistaken identity (Whistler's description is, by his own admission, not absolutely clinching).

(13) While Jerdon (1862_1864) considered it "excellent eating", his mentor Simson (1884) thought only the Shoveler Anas clypeata tasted worse amongst the ducks of India. Whether such variation in palatability reflects variation in human taste or in the ecology of the species (the ecological correlates of pink feathering in wetland birds are worth evaluating in this regard) is not easy to judge.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 25, 2005 18:18:49 GMT

www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/ www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/Pink-headed Duck A much wanted trophy The Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea ( Latham, 1790) once lived in inaccessible swamps of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers in northern India. It has always been considered rare, but this may have been due to the inaccessibility of its habitat. As the swamps became cultivated, this handsome duck was initially seen more frequently. However, reclamation of the swamps inevitably led to the decline of the species in the beginning of the 20th century. Its remarkable appearance made it a favoured hunting trophy, though this is probably not the main cause of its extinction. The British who governed the area found its meat far from tasty. The fast-growing local population may, however, have had a different opinion. The last specimen died far from home As to the exact date of extinction, opinions vary from 1936 or 1939 to 1945. Most likely, the last Pink-headed Duck died far from its native swamps, in a British aviary. During the 1960's its presence was claimed near the Burmese-Tibetan border, but this may be based on misidentified Red-crested Pochards Netta rufina. In any case, the claim has not been substantiated. The museum collection The National Museum of Natural History possesses one male from India. Collector and collecting date are not known. Over 70 skins are preserved worldwide. |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Feb 3, 2006 8:35:40 GMT

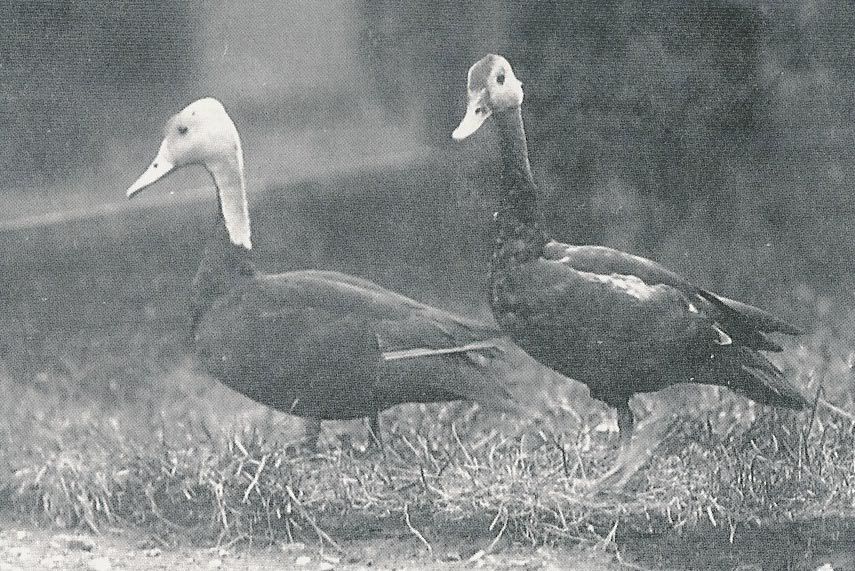

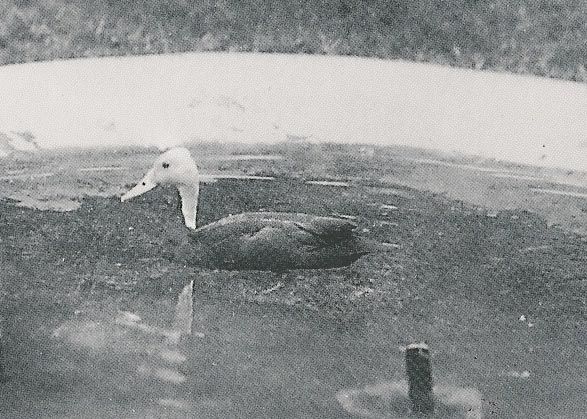

Here is two photos of living Pink-headed ducks taken 1926 in Foxwarren Park, Surrey, England.   |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 4, 2006 20:17:32 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 4, 2006 20:18:29 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 4, 2006 20:19:40 GMT

|

|

peej2

Full Member

Posts: 118

|

Post by peej2 on Mar 14, 2006 5:01:38 GMT

Where did you aquire those images of the pink headed duck? There really good pics. It's hard to find such good pics of an extinct animal.

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Mar 14, 2006 7:17:06 GMT

Errol Fuller "Extinct Birds". A very good book and worth to buy. Where did you aquire those images of the pink headed duck? There really good pics. It's hard to find such good pics of an extinct animal. |

|