|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 27, 2005 9:05:59 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 27, 2005 9:06:19 GMT

Fossilised giant tortoise found In addition to the Dodo remains, the find included bones of various other extinct bird species, indigenous giant tortoise species, and a baby giant tortoise, as well as a large number of seeds and remains of (partly) extinct trees and plants. Further studies of the Mare aux Songes site's geology and ecology are expected to reconstruct the area's landscape, wildlife, and vegetation, determining if the animals may have perished en masse due to a natural disaster. In addition, the studies will enable scientists to research how such a massive collection of bones, seeds, and wood ended up in the swamp and how it has remained so well preserved. The studies will be carried out by local botanical specialists from Mauritius in close co-operation with leading European institutes from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The Dodo was a flightless member of the pigeon family native only to the island of Mauritius. The Portuguese, arriving on the island in 1505, shot the Dodo for fresh meat eventually wiping out the species in 1681. It was the first known animal species to be wiped out by the actions of man and not the evolution of nature. Of the 45 bird species originally found on the island, only 21 still survive. www.news24.com/News24/Technology/News/0,,2-13-1443_1855105,00.html tinyurl.com/75blh |

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Jan 28, 2006 19:13:44 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 31, 2006 19:37:07 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Feb 4, 2006 13:38:21 GMT

I've updated my dodo page a bit: www.petermaas.nl/extinct/speciesinfo/dodobird.htmAnd here some photos:  Reconstruction of the dodo. Copyright © Peter Maas.  Reconstruction of a dodo skull from the National Museum of Natural History 'Naturalis' in Leiden, the Netherlands. Copyright © Peter Maas.   Photos: a new and the old dodo reconstruction. Photographed by Peter Maas (2002) at a temporary dodo exposition in the National Museum of Natural History 'Naturalis' in Leiden, the Netherlands.    Photo: Drawing of a dodo by an anonymous hand in the journal of the Dutch ship the Gerlderland (c. 1601). Original in Rijksarchief, The Hague, the Netherlands. Photographed by Peter Maas (2002) at a temporary dodo exposition in the National Museum of Natural History 'Naturalis' in Leiden, the Netherlands.  Photo: Dodo skull. Photographed by Helle Jørgensbye at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark. Copyright © Danish Zoological Society.  Photo: Nicobar Pigeon at Bristol Zoo, Bristol, England. Photographed by Adrian Pingstone in August 2003 and placed in the public domain. Closest still living Dodo relative! |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 14, 2006 21:01:53 GMT

thanks for uploading pics Peter - makes the page more interesting having images

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2006 21:56:09 GMT

not sure if this pic is repeated but here it - another from my computer |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on May 26, 2006 20:21:26 GMT

New Dodo expedition!From 2 June to 3 July 2006 a team of Dutch, British and local biologists, geologists and archaeologists will dig for dodo bones on Mauritius. The expedition is a continuation of the particular find of autumn 2005, when Dutch and local researchers did find unique dodo material. The Dutch research institutes TNO Bouw en Ondergrond (Geological Survey of the Netherlands) and Naturalis (Leiden Museum) will work together during the research. Expedition members cherish the quite hope to find a complete skeleton or bones of chickens during systematic digs in the old site Mare aux Songes. Certain is that they will find besides dodo bones also remains of other animals and plants. The finds will be studied scientifically during the next three years. The goal is to reconstruct the ecosystem in which the dodo lived. The researchers want also once and for all answer the question on what has been the cause of the disappearance of the dodo and its environment. The researchers will maintain a weblog during the research period. This weblog can be found at: www.dodo-expeditie.nl (in Dutch). Information can also be found through www.naturalis.nl. An English summary with information on the expedition and research can be found in this online pdf.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jun 14, 2006 8:07:44 GMT

Driven to extinction: Who killed the Dodo? Its name has passed into common parlance as a byword for obsolescence. But now a new expedition hopes to shed more light on an iconic bird. Steve Connor reports Published: 09 June 2006 For such an iconic animal, it seems strange that we know next to nothing about the dodo - except, of course, that it is dead. We don't know how it lived, what it ate, how many eggs it sat on or even whether it was fat or thin. But that could all change with a scientific expedition just begun in Mauritius, the remote island in the Indian Ocean where the dodo lived for millions of years before being driven to extinction in the late 17th century, just 80 years after it was sighted by European sailors. British and Dutch scientists have joined forces to excavate a unique dodo burial ground where the bones of hundreds and possibly thousands of birds have been preserved in marshland for more than 10,000 years. It will be the first time scientists have had access to well-preserved dodo remains that have remained untouched. At last, some light maybe shed on a mysterious and emblematic creature that has come to epitomise how easy it is for man to wipe out a species. The Mare aux Songes area of Mauritius was once a dry coastal forest which later became marshland. Last year scientists said they thought the site contained a mass of bones from a rich variety of animals - giant tortoises, dodos and other extinct birds and reptiles - all of which long pre-date the arrival of the first humans to inhabit Mauritius in 1598. "The discovery is of huge importance and will give us a new understanding of how dodos lived," explained Julian Hume, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Natural History Museum in London who has helped to organise the expedition. "For the first time we will be able to answer questions like how many dodos lived on the island and what did they eat? Young dodo remains may also reveal how they bred and what kind of parents they might have been," Dr Hume said. "We still don't even know what it ate and why it had that unusually large, hooked bill. It may have been for sexual display or was it to dig out roots for eating? These are some of the questions we want to answer." The first written description of a dodo comes from a Dutch sailor called Heyndrick Dircksz Jolinck, who led an expedition to the island in 1598. He described large birds with wings no bigger than a pigeon's - the wings were so small they rendered the birds flightless. Jolinck also gave a strong hint about why the dodos became so sought after by sailors. "These particular birds have a stomach so large it could provide two men with a tasty meal and was actually the most delicious part of the bird," he wrote. Although hunting and indiscriminate killing was to take their toll, it was the invasion of the island by alien species such as rats, pigs and other domestic animals that saw the dodo condemned to extinction. The chicks and eggs of the ground-laying bird became easy fodder. Habitat destruction also played its part and by 1680, just eight decades after the island was claimed as Dutch territory, the last dodo had died. All that remained were a few moth-eaten specimens in European museums. The most famous was the Oxford dodo, which became so badly decomposed that much of it had to be burnt. Only the head and one leg remains today at the University Museum. It was this specimen that was probably the inspiration for Lewis Carroll's "Dodo" in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Intriguingly, according to Dr Hume's research, is it also possible the Oxford dodo was the only living specimen to have arrived in Europe. This bird was described by Sir Hamon L'Estrange in London in 1638. He saw a picture of an unfamiliar "fowle" hanging upon a cloth outside a shop - clearly an advertisement to see a strange bird - which led Sir Hamon to investigate. His subsequent description is the only documented account of a living dodo in Britain. "It was kept in a chamber, and was a great fowle somewhat bigger than the largest Turkey Cock, and so legged and footed, but stouter and thicker and of a more erect shape, coloured before like the breast of a young cock fesan, and on the back a dunn or deare colour. The keeper called it a Dodo, and in the ende of a chymney in the chamber there lay a heape of large pebble stones, wherof hee gave it many in our sight, some as big as nutmegs, and the keeper told us she eats them (conducing to digestion)." Much of what is known about the appearance of the dodo comes from contemporary drawings and paintings. But these were often inaccurate, subject to the vagaries and fashions of the time - such as the 17th century predilection for painting over-plump birds. "The dodo, one of the most documented and famous of birds and a leading contender as the icon of extinction, has endured more than its fair share of overzealous misinterpretation," said Dr Hume, who is himself a skilled artist. After the last dodo was seen alive, it quickly became an almost mythical creature for sailors and travellers. In fact it became so mythologised that some eminent 19th-century scholars began to doubt that it ever existed, believing that the rather poorly preserved specimens were elaborate hoaxes. In fact all of these specimens were made from the incomplete skeletons of many different individuals. Trying to guess what the real dodo looked like was an uphill struggle. One problem was its weight. Many of the early paintings depict it as an overweight, almost obese creature that could barely support itself. But, at least one illustration dating from the first Dutch exploration of 1598 depicts the dodo as a rather slim, even nimble bird. In reality, it is possible that the dodo was both fat and slim. In other words it may have been adapted to putting on weight quickly in times of plenty - during the wet season for instance when there was lots of ripe fruit to eat - which would have allowed it to survive the leaner times of the dry season. Dodos kept in captivity could just have been overfed, which is why they tended to look far fatter than other birds of similar shape and size. Lingering 19th-century doubts about the existence of the dodo were finally dispelled in 1865 with the discovery of the bones of about 300 dodos that had died out long before the arrival of the first Europeans to Mauritius. Unfortunately this excavation was not undertaken in a very scientific manner and many of the specimens were mishandled, leading to further confusion about the dodo's true anatomy. The site where these bones were found was subsequently filled in by the British military in the 1940s using builders' rubble. It was recently earmarked for further development when Dr Hume and his colleagues decided to seek permission to dig below the builders' hardcore. Last December they announced they had struck palaeontological gold with the discovery of a new, untouched layer of thousands of bones dating back at least 10,000 years. "This is new material and it is absolutely free of human contamination. We're going to collect material that has not been touched in any shape or form," Dr Hume said. One hope is that the scientists will find the first complete articulated skeleton of an individual dodo, which will help them to figure out how it moved around, whether it walked with a waddle or hopped with a skip. The bones are so well preserved that the researchers also hope to extract DNA that will give further insights into the bird's origins. Professor Alan Cooper, former director of the Ancient Biomolecules Centre at Oxford, has already been able to extract limited quantities of DNA from the Oxford dodo - the only specimen with soft tissue. This study revealed the dodo was related to the solitaire, another extinct bird that lived on nearby Rodrigues Island, which is part of the same Mascarene island chain. "The data suggests that the dodo and solitaire speciated [separated] from each other around 26 million years ago, about the same time that geologists think the first, now submerged, Mascarene islands emerged," Professor Cooper said. " Mauritius and Rodrigues islands are much younger - eight and 1.5 million years respectively - implying the dodo and solitaire used the now sunken island chain as stepping stones." Most intriguingly, the DNA study showed that the dodo was in effect a giant pigeon. Its nearest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon from south-east Asia. The next nearest relatives are the crowned pigeons of New Guinea and the tooth-billed pigeons of Samoa. The unusual looks of the dodo - epitomised by the oversized, hooked beak - were the result of the unusual forces of natural selection that often occur on remote islands. When large animals get stranded on islands they tend to become dwarfs, while smaller animals such as birds tend to get bigger in order to build up bulk for times of near starvation. This is precisely what happened to the dodo. It quickly lost its flight muscles - which are expensive to maintain in terms of energy - because there were no predators on the island from which to escape. That all changed in 1598 when the first European settlers decided to set up home in dodo land. The rest - like the dodo - is history. news.independent.co.uk/world/science_technology/article753704.ece |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jun 29, 2006 9:56:50 GMT

New Dodo expedition!From 2 June to 3 July 2006 a team of Dutch, British and local biologists, geologists and archaeologists will dig for dodo bones on Mauritius. The expedition is a continuation of the particular find of autumn 2005, when Dutch and local researchers did find unique dodo material. The Dutch research institutes TNO Bouw en Ondergrond (Geological Survey of the Netherlands) and Naturalis (Leiden Museum) will work together during the research. Expedition members cherish the quite hope to find a complete skeleton or bones of chickens during systematic digs in the old site Mare aux Songes. Certain is that they will find besides dodo bones also remains of other animals and plants. The finds will be studied scientifically during the next three years. The goal is to reconstruct the ecosystem in which the dodo lived. The researchers want also once and for all answer the question on what has been the cause of the disappearance of the dodo and its environment. The researchers will maintain a weblog during the research period. This weblog can be found at: www.dodo-expeditie.nl (in Dutch). Information can also be found through www.naturalis.nl. An English summary with information on the expedition and research can be found in this online pdf. ¨ Dutch paleontologists find remains of dodo 1 hour, 36 minutes ago THE HAGUE (AFP) - A team of Dutch paleontologists has discovered the remains of the lower half of a dodo, the long-extinct flightless bird which once inhabited the island of Mauritius, the natural history museum in the western Dutch town of Leiden said. Among the remains discovered by the scientists investigating the ecosystem in which the dodo lived on the Indian Ocean island 500 years ago are a hip and the four bones of a leg attached to it, the museum said. They also found a beak, vertebrae and the wings of the dodo. The dodo was discovered in 1598, but extinct by 1681, after falling prey to mainly European colonizers and the dogs, pigs and rats they brought along. The dodo was a rather plump bird, weighing approximately 23 kilograms (50 pounds) as an adult. Grey in colour, it had a large, hooked beak, and a plume of white feathers adorned its rear. Few remains have been found. What distinguished it from many other birds was not just its size, but that it was flightless, having small weak wings which could not lift it into the air. The search of the dried marshland was launched by the Dutch paleontologists after the discovery last October of a large undisturbed layer of dodo remains. Before the end of their mission the researchers hope to find a full skeleton. |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Jun 29, 2006 19:32:30 GMT

Latest press release of the Leiden Museum on the dodo expedition (translated from Dutch into English): Expedition team find the first Mauritius Blue Pigeon bones Leiden, the Netherlands, 29 June 2006. The excavations on Mauritius of an international research team have led to the discovery of the first bones ever found of the Mauritian Blue Pigeon ( Alectroenas nitidissima). Besides the bones of the Mauritian Blue Pigeon and the Dodo (see previous post), there have also been found remains of another 13 extinct animal species in the Mare aux Songes excavation site. The last Mauritian Blue Pigeon, named after its red-white-blue feathers, was presumably shot dead in 1826. Worldwide there are only three skins of this bird preserved, but never before any bones were found. Other finds are the beak and bones of one of the world largest parrots ( Lophosittacus mauritianus) and bones of the Mauritian Red Rail. Besides birds they also found two complete shells of two giant tortoises ( Cylandrispis sp.), along with bones of flying foxes and the giant skink Didosaurus. This lizard could reach a lenght of 50 cm en was probably the largest skink in the world. Besides an almost complete fossil fauna, they have also discovered seeds of several plant species in Mare aux Songes. Because of the finds of the team they can sketch a complete picture of the world of the dodo ( Raphus cucullatus), before man set foot on the island. The expedition will shed light on the cause of disappearance of the dodo and the unique ecosystem it lived in. The excavations in Mare aux Songes will continue until 3 July 2006. The total research will continue until 2009. At the end of September 2006 there will be a seminar at the Oxford University where the results will be presented. A part of the found materials will be this year on display in the Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum Naturalis (Leiden National Museum of Natural History) in Leiden, the Netherlands. www.naturalis.nl |

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Jul 9, 2006 17:50:00 GMT

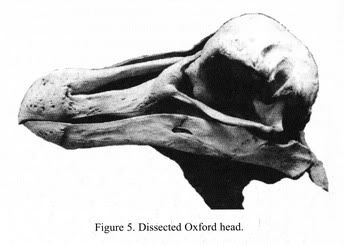

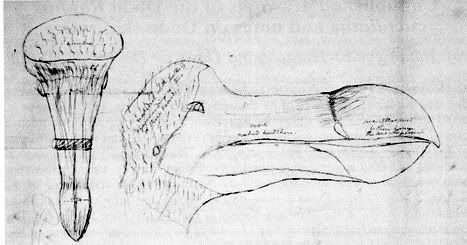

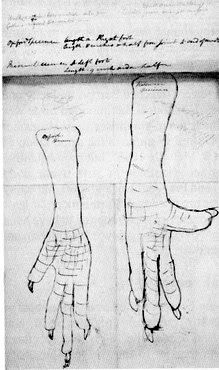

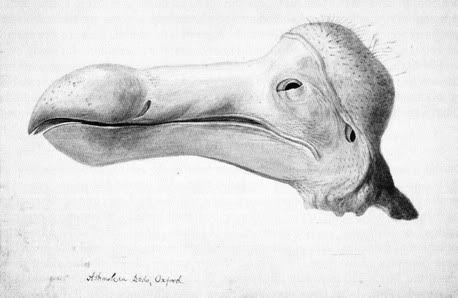

Unpublished drawings of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and notes on Dodo skin relics by Julian Pender Hume, Anna Datta & David M. Martill Bull. B.O.C. 2006 126A: 49-54. The Dodo Raphus cucullatus was an endemic giant flightless pigeon from Mauritius that died out within 100 years of its discovery in 1598 (Moree 1998, Hume et al. 2004) It has become a metaphor for extinction, exemplifying man's destructive capabilities on endemic oceanic island species (Fuller 2002). Our scant knowledge of the Dodo's morphology and autecology is derived largely form historical accounts, including contemporary paintings and ship's records, although there has been a debate as to their scientific accuracy (Kitchner 1993). Knowledge of the skeletal anatomy of the Dodo is more detailed, being derived mainly from fossil remains discovered in the Mare aux Songes in the 1860s (Owen 1866). Very few Dodo remains reached European shores, and thus very few scientist have ever had 'hands-on' experience of this enigmatic bird. Such was the paucity of tangible evidence for the existence of the Dodo that in the early 19th century many considered the species to have been mythical (Strickland & Melville 1848). Here we announce the discovery of 19th-century illustrations of a Dodo foot, executed by John Edward Gray, while searching the archives in the general library of the natural History Museum, London. Although a number of exotic species were brought back to Europe in historic times, the inability to keep animals alive, or to preserve dead material on long sea voyages in the 1600s, resulted in comparatively few zoological specimens reaching European shores. Despite suggestions to the contrary (e.g. Hachisuka 1953), as few as four of five Dodo specimens -maybe even fewer- reached Europe, and only one, perhaps two birds arrived alive (Hume in press). Amongst the imported birds was the so called 'Oxford Dodo', a specimen which today comprises the only extant skin remains. It has been suggested that the Oxford example is the same Dodo as that seen alive in London in 1638 (Strickland & Melville 1848), but no substantive evidence to support this claim exist. Further examples of soft tissue dodo specimens once existed in Copenhagen (head) and Prague (beak and foot), but today only the bones are preserved and their histories are uncertain. Furthermore, at least one other specimen of a dodo, if indeed it was actually so, was reported to have been deposited at the Anatomy School, Oxford (e.g. Newton & Gadow 1896), but again, its provenance and subsequent history are unknown. Brief historical review The Oxford Dodo has a complex history, having been exhibited as a stuffed bird in the collection of horticulturist John Tradescant (Tradescant 1656), in 1656, and bequeathed to Elias Ashmole in 1659 (Strickland & Melville 1848). The specimen remained in the Ashmolean Museum until its transfer to the Oxford University Museum during the 1850s. There was a long-held belief that this, by then unique, stuffed Dodo was thrown onto fire in 1755, and that only the head and a foot were rescued from the flames (e.g. Strickland & Melville 1848, Fuller 2002). In fact, its removal from exhibition was a curatorial decision made to preserve what was left of the by then highly degraded specimen (Ovenell 1992). The salvaged remains included the skin of the head, some feathers and a foot. Today, all that remains of this specimen are two halves of the skin of the head, now with very few feathers, the skull, and the bones of the right foot with some scraps of skin and sinew (Figs. 4-5).  Figure 4. Oxford foot bones Figure 4. Oxford foot bones Another Dodo foot termed the 'London foot', which could be seen in a residence formerly called the Music House, situated near the West End of St Paul's church, London, was collected by Hubert alias Forges (Forges 1665). It was presented to the Royal Society of London an transferred to the former British Museum, where it was exhibited along with the most famous Dodo painting (Strickland & Melville 1848), once owned by George Edwards and affectionately known as 'George Edward's Dodo', painted by Roelandt Savery in c. 1626 (still held in the library of the Natural History Museum [NHM]). The last definite mention of this specimen including the soft tissue was c. 1848 (e.g. Richardson 1851). The foot was mentioned again by Newton & Gadow (1896) as 'still reposing in the British Museum, but without its integuments'. This suggest that like the Oxford specimen, the London specimen's soft tissue had decayed or been dissected and in fact the foot, as originally depicted in Strickland & Melville (1848), no longer existed. Therefore it is likely that today the so-called missing foot (e.g. Fuller 2002) consist only of bone (after being cast) and researchers loking for the soft tissue specimen are, in fact, searching for the wrong type of material. Thus, by the end of the 1800s very little tangible non-fossil Dodo material was available for study. The Oxford Dodo head was dissected and illustrated in 1847, along with the London foot (Strickland & Melville 1848). The Oxford foot was also dissected, but by this time it lacked most of its soft tissues and, until recently, was never thought to have been illustrated with integuments. Newly discovered illustrations During a search of the zoological drawings held at the NHM, London, one of us (AD) discovered a folder entitled ' Didus' (Linnaeus's second but junior synonym for the Dodo) compiled by John Edward Gray (1800-75). Gray joined the staff of the then British Museum (now NHM) as an assistant in 1824, becoming Keeper of Zoology in 1840 until his retirement in 1874 (Anon. 1904). Gray amassed a large collection of published natural history illustrations in scrapbooks and also produced some drawings of his own. The ' Didus' folder contained one double-sided sheet measuring 340 x 210 mm with illustrations in black ink on paper bearing an 1824 watermark (Figs. 1-2). Gray presented these dodo illustrations to the Zoological Club of the Linnaean Society on 24 April 1828 (Anon. 1828) and, therefore, the pictures must have been executed during this four-year period. A short note was published and this is the only mention made of Gray's dodo sketches we have managed to trace: 'At the request of the Chairman, Mr. Gray exhibited a sketch of the foot of the dodo, Didus ineptus, L., [Raphus cucullatus] preserved in the British Museum, and another sketch of that contained in the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford, and also a head remaining in the latter collection. He remarked that the feet agreed so perfectly in characters as to leave no doubt of their having belonged to the same species, but that although they were of opposite sides, the one being left and other right, they must have been obtained from different individuals, the Oxford specimen being one inch shorter than that of the British Museum.'  Figure 1. Newly discovered unsigned illustrations of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus head in dorsal and lateral views, Figure 1. Newly discovered unsigned illustrations of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus head in dorsal and lateral views,

executed by John Edward Gray, c. 1824. Figure 2. Only known illustration of the 'Oxford Dodo' foot alongside the 'London foot'. Figure 2. Only known illustration of the 'Oxford Dodo' foot alongside the 'London foot'.

The Oxford foot is more gracile and 11% smaller than the latter.

They are interpreted as male (London) and female (Oxford).

Annotations on Gray's hand give dimensions of the feet.On one side of the drawings is illustrated the Oxford head in dorsal and lateral wiews (Fig. 1) whilst the other side illustrates, uniquely the Oxford and London dodo feet (Fig. 2), with accompanying annotations including measurements. On the first sheet accompanying the dodo feet the following measurements are presented: Oxford Specimen. Length a. Right foot Length. 8 inches & half from joint to end of middle toe Museum [London] Specimen. B. left foot Length. 9 inch and a half. On the second sheet accompanying the dodo head drawings the following notes are made: [dorsal view, left] 4 inches [across head], 2.1/4 [in front of eyes], 1.1/4 [across tip of bill]. [lateral view, right]; nakedish with scattered hairs ending in two or three heads [written o head]; cere naked hard skin [in the middle]; cover of this part is thin. horny. the bone solid. porous [on bill tip] Whilst examining Sir Richard Owen's correspondence in the same library, JPH found a hitherto unpublished illustration of a Dodo head. The watercolour is signed 'WC' (William Clift, 1775-1849, conservator of the Hunterian collection, London) and comprises an illustration of the head of the Oxford Dodo specimen prior to its dissection (Fig. 3). Of particular note in this ilustration is the presence of many head feathers that have subsequently disappeared. The discovery of Gray's previously unpublished illustrations constitutes the only scientific documentation of all known skin specimens of the Dodo illustrated together. This is particularly important for comparative study.  Figure 3. Head prior to dissection, executed by William Clift Figure 3. Head prior to dissection, executed by William CliftDiscussion Based on the handwritten measurements by Gray, the Oxford right foot is c. 11% smaller and more gracile than the London foot, yet the tarsometatarsus bone of the Oxford foot has fully-fused epiphyses, indicating the animal to be adult (Fig. 4). Such a size discrepancy in a Columbiform has been interpreted as representing sexual dimorphism (Livezey 1993). Gray's illustration certainly indicates that the London foot is larger than the Oxford foot, but virtually nothing is known of dodo ecology. Therefore, any interpretations based on these drawings must be made cautiously. |

|

|

|

Post by dysmorodrepanis on Sept 1, 2006 17:18:01 GMT

I just noticed something which came as quite a shock: Regarding the dodo-Nicobar Pigeon connection - the idea that the Raphidae should be synonymized in the Columbidae is ridiculous. Simply because they are a derivate of some pigeon is not enough; at some point, a lineage is distinct enough, paraphyly or not, to have embarked on an evolutionary voyage completely separated from its ancestors. By the same reasoning, ALL land vertebrates must be sunk into Osteichthyes because lungfishes are closer to land vertebrates than to herrings. One can continue this ad nauseam, because cladistically, even humans are nothing more than megalomaniac archaeans or at the very least protists. But evolution does not work as clean as PhyloCode and similar theoretical constructs would require to be usable. Now, to the main point: The Shapiro study (Dodo + Nicobar pigeon + crowned pigeons + Didunculus) used mtDNA 12S and cyt B sequences. The latter at least was utterly unable to resolve the relationships of the critical group of columbids in this www.inhs.uiuc.edu/~kjohnson/kpj_pdfs/MPE.Johnson.Clayton.2000.pdf study. And that is a problem, because especially if one takes into account long-branch attraction, degradation etc, the "fact" that the dodo lineage's closest living relative is the Nicobar Pigeon is a nice hypothesis, but nothing more. The phylogeny of the "Flight of the Dodo" paper contains several inconsistencies, e.g. the placement of Gallicolumba becarii makes no sense at all; the placement of Treron is objectionable to say the least, and so on. It seems that cyt b at least should not be used to reconstruct phylogenies of the Indoaustralian columbid radiation, and that renders the "Flight of the Dodo" paper, unfortunate as that is, damn close to null and void. At least, the conclusion that the Nicobar Pigeon is the dodo/solitaire's closest liveing relative cannot be taken at face value.  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 11, 2006 18:36:23 GMT

Here is one of the world famous paintings of the Dodo. Painted in 1628 by Flamian master Roelant Savery Title: Landscape with Birds Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna  |

|

|

|

Post by dysmorodrepanis on Sept 12, 2006 0:50:28 GMT

It has also one of the mystery macaws sitting at the left; the blue-and-yellow bird that has been supposed to be A. martinica or A. erythrura.

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Nov 5, 2006 11:46:53 GMT

Hi ! I made this Dodo scetch today, I used the photograph of a skeleton and the drawing of the Dodo which is now in Petersburg as model.  |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 5, 2006 12:36:17 GMT

Nice sketch Noisi

|

|

|

|

Post by dysmorodrepanis on Nov 7, 2006 0:10:16 GMT

Definitely one of the best I ever saw.

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Nov 7, 2006 9:25:11 GMT

Thank You, guys !

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 6, 2007 18:13:32 GMT

Skeleton of the Dodo, a famous extinct bird who once lived on the island of Maurice. Photographed at the MNHN in Paris. The Dodo died out in the 16th century, unfortunately, the last stuffed specimens housed at the natural History Museum in London looked "too shabby" so that they were thrown away. Nowaday, no one really knowns how a Dodo looks like. flickr.com/photos/92043060@N00/330268267/ |

|