|

|

Post by Melanie on May 31, 2005 2:06:44 GMT

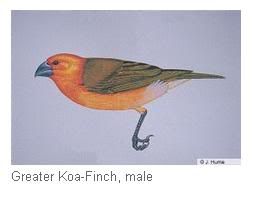

GREATER KOA-FINCH (Rhodocanthis palmeri) Ex Formerly Endemic to Kau and Kona districts of Hawai'i. Not seen since 1896. Males were large with brownish upperparts and short brown tail. The underparts were orangey-brown, paling towards the lower belly. The undertail-coverts were white. The head was bright orange-red. The bill was large and gray. Females were like Lesser Koa-Finch but probably slightly paler below and slightly larger. Immature males apparently had heads which were yellowy, but never as bright as male Lesser koa-Finches. (9 inches) Calls: A clear, quiet whistle, and several whistled flute-like notes, more prolonged at the end. Like the former species, Greater Koa-Finches were confined to one side of Hawai'i above 1000 meters, and lived in the same habitats and behaved similarly to Lesser Koa-Finches. There is the possibility that only one species was actually involved "Koa Finch" and that Lesser and Greater Koa-Finches were actually just extremes of one species - much debate has ensued on this subject.  |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 4:29:01 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 5:42:22 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Nov 1, 2005 17:48:43 GMT

Hi ! Rhodacanthis palmeri:  Bye Alex |

|

|

|

Post by dysmorodrepanis on Nov 2, 2005 19:23:54 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Nov 2, 2005 19:25:02 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 2, 2005 23:23:42 GMT

Thanks for the info to dysmorodrepanis it's of great interest

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 6, 2005 19:30:08 GMT

gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 21:23:28 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 28, 2008 7:50:45 GMT

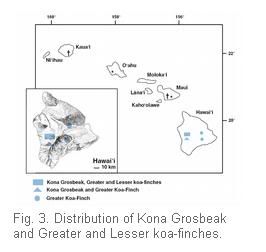

These 3 large Hawaiian finches, among the least known of the Drepanidinae, share remarkably similar and dismal histories. All were known historically mainly or entirely from a limited area on the Kona (western, leeward) side of the island of Hawai‘i, although the fossil record shows that the same or closely related species once probably occurred throughout the main Hawaiian islands. All 3 were first discovered by ornithological collectors in the waning years of the nineteenth century, were apparently unknown to native Hawaiians at the time, and disappeared forever in less than a decade following their discovery. There are no credible records of any of the species after the last specimens of each were taken. The only published observations of these birds in life come from Scott Wilson’s first and brief exposure to the Kona Grosbeak (Wilson 1888, Wilson and Evans 1890–1899); from Walter Rothschild’s collectors Henry Palmer (Rothschild 1892, 1893–1900) and George C. Munro (1944); and from the naturalist R. C. L. Perkins (Perkins 1893, 1903). Although these published sources have been cited time and again, because all the species are extinct there is no recourse but to turn to them once more. The present compilation augments these traditional sources with much original data from a thorough check of world museum collections for all extant specimens of the 3 species, as well as with original observations from G. C. Munro’s unpublished field journal in the B. P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu (cited throughout this account as “Munro journal”). The Kona Grosbeak (also called Kona Finch or Grosbeak Finch) was first obtained on 21 June 1887 by Wilson and last collected in September 1892 by Perkins, the period of its historical existence thus lasting 5 years and 6 months. Munro (1944: 131), who was evidently the source for the last year of observation given by Berger (1972) and Grant (1995), credits Perkins with encountering this species in 1894, but Perkins made no mention of a sighting in 1894, either in publication (1903) or in his field notes (Banko 1986), and no specimens exist with such a date. Thus Banko (1986) is correct that the last evidence of the species is from 1892. Palmer shot the first Greater Koa-Finch (also called Orange Koa-Finch) on 26 September 1891, and Perkins took the last specimens in March 1896, giving the species a historical existence of only 4 years and 6 months, even though it persisted for three and a half years longer than the Kona Grosbeak. The Lesser Koa-Finch (also called Yellow-headed Koa-Finch) was obtained only by Palmer and Munro, who collected their first specimen on 30 September 1891 and their last on 16 October of the same year, for a total historical existence of only 17 days. Historically, these 3 species were confined to mesic forests at middle elevations on the drier, leeward slopes of the island of Hawai‘i; only the Greater Koa-Finch was found elsewhere. The Kona Grosbeak was closely associated with the naio, or bastard sandalwood, tree (Myoporum sandwicense) growing on relatively recent ‘a‘a lava; its massive beak, hypertrophied jaw muscles, and “thick tongue like a parrots” (Munro journal: 25 Sep 1891) were adaptations for processing the small, very hard fruits of that plant. The beaks of the koa-finches, as their name implies, were adapted for cutting the green pods of the leguminous koa tree (Acacia koa). The stomachs of the koa-finches were very large and thin-walled for processing large masses of vegetable material, in contrast to the much smaller gastrointestinal tract of the Kona Grosbeak (Perkins 1903, Munro 1944). All 3 species had the characteristic drepanidine odor “in a marked degree” (Perkins 1903: 440), and the flesh of the koa-finches was also reported to have a strong odor (Munro 1944). Although each species varied its diet somewhat, the birds were undeniably specialized feeders and doubtless could not have survived in places where their principal food plant was absent. There is no evidence that native Hawaiians in the nineteenth century had any knowledge of these species. Perkins (1893), followed by Wilson and Evans (1890–1899), applied the name “palila” to the Kona Grosbeak, but this was merely a lapse intended for Loxioides bailleui, to which the name belongs. Of the Greater Koa-Finch, Palmer stated that “natives on Hawaii called the bird ‘poupou’ and ‘Hopue,’ but did not seem to be well acquainted with it” (Rothschild 1893–1900: 204), but Perkins (1903: 440) considered the accuracy of this statement to be very doubtful, saying that “natives with a really extensive knowledge of the avifauna, to whom the skins were shown, declined to give them a name, and even suggested that they were ‘malihini’ (foreign).” The history of these 3 enigmatic finches, whose discovery was nearly simultaneous with their disappearance, has been the source of considerable wonder. What were the causes of such restricted distributions and almost instantaneous disappearance? In light of the massive loss of species diversity and island populations shown by the fossil record (James and Olson 1991, Olson and James 1991), the extinctions seem less remarkable, a few among many. Perhaps speculation should focus instead on what caused the prolonged survival of these 3 finches in the Kona District of Hawai‘i I., when all other populations of their relatives had long since been extinct. bna.birds.cornell.edu/ |

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Nov 28, 2015 20:50:58 GMT

"Living Things Vanished from the Earth (in Japanese)" by Toshio Inomata (1993) from above to below with Laysan rail Molokai 'O'o Greater Koa Finch, Kioea, Hawaiian rail Kona Grosbeak, Hawaiʻi Mamo, Greater Koa Finch Greater Amakihi, Black Mamo, Ula-ai-hawane |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 19, 2016 8:39:35 GMT

|

|