|

|

Post by Melanie on May 31, 2005 2:09:28 GMT

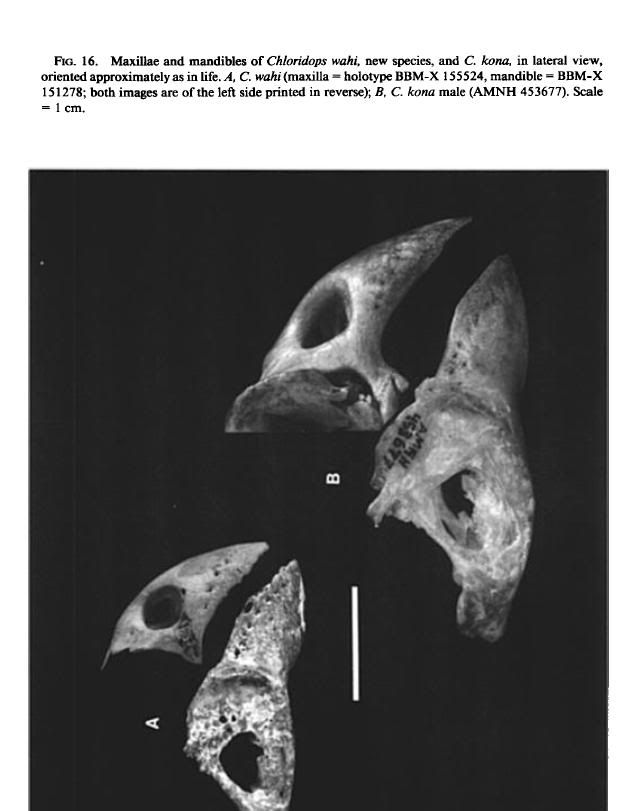

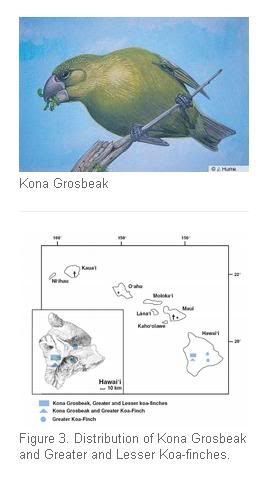

Kona Grosbeak Chloridops kona (Wilson, 1888) Status: First discovered on 21 June 1887. It was last seen and collected in September 1892 (Pyle & Pyle, 2017). Museum specimens: At least 57 specimens in world collections. Including Torino (MZUT). Taxonomy: Monotypic species. Distribution: Endemic to Hawaii, Hawaiian islands. Natural HistoryIt was a frugivore which almost exclusviely fed upon the extremely hard endocarp of dried naio fruits (Myoporum sandwicense), on very rough lawa flows and in forest openings on the slopes of Mauna Loa Volcano at elevations of 1,400–1,700 m (Olson, 1999b; 2014). It may have also taken green naio fruit and leaves (Pratt, 2002). May have opportunistically taken softer fruits because pollen found in feathers of specimens (Cox & Elmqvist, 2000). Olson (1999b) suggested that fruit size may have been a limiting factor in distribution because naio within the range has smaller fruits with more seeds per fruit than elsewhere (Wagner et al., 1990). It was a sluggish and inconspicous bird easily overlooked except for the cracking sounds of its feeding (Perkins, 1903). It was usually observed in pairs or small family groups (Pratt, 2002). Breeding probably took place in fall-spring as in many other honeycreepers, because specimens takin in July-October was not in breeding condition (Olson, 1999) and birds encountered in small groups that Perkins (1903) regarded as adults leading young. Conservation StatusIt was already very rare and known only from a 10km2 area when first discovered by Scott B. Wilson, who observed two individuals and collected the type specimen on 21 June 1887 while staying in the vicinity of Pu`u Lehua ranch (1,470 m) on the slopes if Hualalai above Captain Cook (Wilson, 1888; Wilson & Evans, 1899). He observed no others during a four-week stay and he considered them to be "extremely rare" (Munro, 1944). But Palmer and Munro found them to be fairly common in this area in 1891-1892, collecting at least 31 specimens, including 12 on 12 October 1891 out of small groups (5-10 birds) observed among "kipukas (oases of vegetation) within a large lava flow south of the ranch (). Palmer also collected one and observed others along the slopes of Manua Loa, as far south as Ka`ohe Ranch (). Perkins (1893; 1903) collected another 21 specimens near Pu`u Lehua and along the nw slopes of Manua Loa in June-September 1892, with three specimens collected by him in September being the last observations of this species on record. Rumours that Perkins observed them in 1894 seem unfounded as he made no mention of a sighting in 1894, either in publication (Perkins, 1903) or in his field notes (Banko, 1986), and no specimens exist with such a date (Olson, 1999). - References - |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 4:04:43 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 6:36:25 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 19:46:34 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Nov 1, 2005 17:49:57 GMT

Hi ! Kona Finch:  Bye Alex |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 3, 2005 18:57:29 GMT

THE KONA GROSBEAK Remembering One of Hawaii’s Extinct Birds By: Les Drent Already rare when Wilson visited Hawaii, the Kona grosbeak was found at elevations of about 5,000 feet in the Kona district amid the koa forest. In 1887 Wilson was one of the last to observe the bird in life, for it was last reliably sighted in 1894. He saw only three specimens in a four-week stay, and so rare was the bird that it apparently had no name in the Hawaiian language. The bulk of Wilson’s report on the Kona grosbeak (also known as the Kona finch or grosbeak finch) is an excerpt from Robert Perkin’s rather disapproving notes, published in The Ibis in 1893: The Chloridops kona (Kona grosbeak), though an interesting bird on account of its peculiar structure, is a singularly uninteresting one in its habits. It is a dull, sluggish, solitary bird and very silent-its whole existence may be summed up in the words “to eat.” Its food consists of the seeds of the fruit of the aaka (bastard sandal-tree, and probably in other seasons of those of the sandalwood tree), and as these are very minute, its whole time seems to be taken up in cracking the extremely hard shells of this fruit, for which its extraordinarily powerful beak and heavy head have been developed. I think there must have been hundreds of the small white kernels in those that I examined. The incessant cracking of the fruits when one of these birds is feeding, the noise of which can be heard for a considerable distance, renders the bird much easier to see than it otherwise would be. It is mostly found on the roughest lava, but also wanders into the open spaces in the forest. I never heard it sing (once mistook the young Rhodocanthis’ -greater koa finch song for that of Chloridops), but my boy informed me that he had heard it once, and its song was not like that of Rhodocanthis. Only once did I see it display any real activity, when a male and female were in active pursuit of one another amongst the sandal-trees. Its beak is nearly always very dirty, with a brown substance adherent to it, which must be derived from the sandal-tree. The bastard sandal-tree referred to here is more commonly known today as the naio tree (Myoporum sandwicense), which grows primarily on medium-aged lava flows. In his illustration Frohawk has accurately depicted the Kona grosbeak sitting on a branch of the naio tree; the small fruit is also shown. The nondescript olive-green colors are well rendered, as is the heavy beak; the gender is unspecified. Somehow this bird appears disgruntled, as if it knows that extinction lies ahead for its species. www.coffeetimes.com/grosbeak.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 6, 2005 19:32:15 GMT

gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 22, 2006 9:11:19 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 21:28:17 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 27, 2008 19:17:45 GMT

Editor's Note: This account combines coverage of three species of extinct Hawaiian finches: the Greater and Lesser Koa-Finch, and the Kona Grosbeak. The close relationship of these species, and their extinct status, prompted the combined coverage. These 3 large Hawaiian finches, among the least known of the Drepanidinae, share remarkably similar and dismal histories. All were known historically mainly or entirely from a limited area on the Kona (western, leeward) side of the island of Hawai‘i, although the fossil record shows that the same or closely related species once probably occurred throughout the main Hawaiian islands. All 3 were first discovered by ornithological collectors in the waning years of the nineteenth century, were apparently unknown to native Hawaiians at the time, and disappeared forever in less than a decade following their discovery. There are no credible records of any of the species after the last specimens of each were taken. The only published observations of these birds in life come from Scott Wilson’s first and brief exposure to the Kona Grosbeak (Wilson 1888, Wilson and Evans 1890–1899); from Walter Rothschild’s collectors Henry Palmer (Rothschild 1892, 1893–1900) and George C. Munro (1944); and from the naturalist R. C. L. Perkins (Perkins 1893, 1903). Although these published sources have been cited time and again, because all the species are extinct there is no recourse but to turn to them once more. The present compilation augments these traditional sources with much original data from a thorough check of world museum collections for all extant specimens of the 3 species, as well as with original observations from G. C. Munro’s unpublished field journal in the B. P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu (cited throughout this account as “Munro journal”). The Kona Grosbeak (also called Kona Finch or Grosbeak Finch) was first obtained on 21 June 1887 by Wilson and last collected in September 1892 by Perkins, the period of its historical existence thus lasting 5 years and 6 months. Munro (1944: 131), who was evidently the source for the last year of observation given by Berger (1972) and Grant (1995), credits Perkins with encountering this species in 1894, but Perkins made no mention of a sighting in 1894, either in publication (1903) or in his field notes (Banko 1986), and no specimens exist with such a date. Thus Banko (1986) is correct that the last evidence of the species is from 1892. Palmer shot the first Greater Koa-Finch (also called Orange Koa-Finch) on 26 September 1891, and Perkins took the last specimens in March 1896, giving the species a historical existence of only 4 years and 6 months, even though it persisted for three and a half years longer than the Kona Grosbeak. The Lesser Koa-Finch (also called Yellow-headed Koa-Finch) was obtained only by Palmer and Munro, who collected their first specimen on 30 September 1891 and their last on 16 October of the same year, for a total historical existence of only 17 days. Historically, these 3 species were confined to mesic forests at middle elevations on the drier, leeward slopes of the island of Hawai‘i; only the Greater Koa-Finch was found elsewhere. The Kona Grosbeak was closely associated with the naio, or bastard sandalwood, tree (Myoporum sandwicense) growing on relatively recent ‘a‘a lava; its massive beak, hypertrophied jaw muscles, and “thick tongue like a parrots” (Munro journal: 25 Sep 1891) were adaptations for processing the small, very hard fruits of that plant. The beaks of the koa-finches, as their name implies, were adapted for cutting the green pods of the leguminous koa tree (Acacia koa). The stomachs of the koa-finches were very large and thin-walled for processing large masses of vegetable material, in contrast to the much smaller gastrointestinal tract of the Kona Grosbeak (Perkins 1903, Munro 1944). All 3 species had the characteristic drepanidine odor “in a marked degree” (Perkins 1903: 440), and the flesh of the koa-finches was also reported to have a strong odor (Munro 1944). Although each species varied its diet somewhat, the birds were undeniably specialized feeders and doubtless could not have survived in places where their principal food plant was absent. There is no evidence that native Hawaiians in the nineteenth century had any knowledge of these species. Perkins (1893), followed by Wilson and Evans (1890–1899), applied the name “palila” to the Kona Grosbeak, but this was merely a lapse intended for Loxioides bailleui, to which the name belongs. Of the Greater Koa-Finch, Palmer stated that “natives on Hawaii called the bird ‘poupou’ and ‘Hopue,’ but did not seem to be well acquainted with it” (Rothschild 1893–1900: 204), but Perkins (1903: 440) considered the accuracy of this statement to be very doubtful, saying that “natives with a really extensive knowledge of the avifauna, to whom the skins were shown, declined to give them a name, and even suggested that they were ‘malihini’ (foreign).” The history of these 3 enigmatic finches, whose discovery was nearly simultaneous with their disappearance, has been the source of considerable wonder. What were the causes of such restricted distributions and almost instantaneous disappearance? In light of the massive loss of species diversity and island populations shown by the fossil record (James and Olson 1991, Olson and James 1991), the extinctions seem less remarkable, a few among many. Perhaps speculation should focus instead on what caused the prolonged survival of these 3 finches in the Kona District of Hawai‘i I., when all other populations of their relatives had long since been extinct. bna.birds.cornell.edu |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Mar 27, 2014 14:12:58 GMT

Olson 2014. A hard nut to crack: rapid evolution in the Kona Grosbeak of Hawaii for a locally abundant food source (Drepanidini: Chloridops kona). Wilson J Ornithol 126(1): 1–8. [ abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Jul 13, 2014 17:45:50 GMT

From 'Hume J.P. & Walters M. (2012). Extinct birds. London: T & AD Poyser, 544 pp. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.':

"A specimen taken in September 1892 by Perkins (not in 1894as often cited, e.g. Munro 1944) was the last known (Banko 1986; Olson 1999a)."

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 19, 2016 8:52:56 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Sebbe on Mar 17, 2019 9:46:21 GMT

|

|