|

|

Post by Melanie on May 31, 2005 2:25:51 GMT

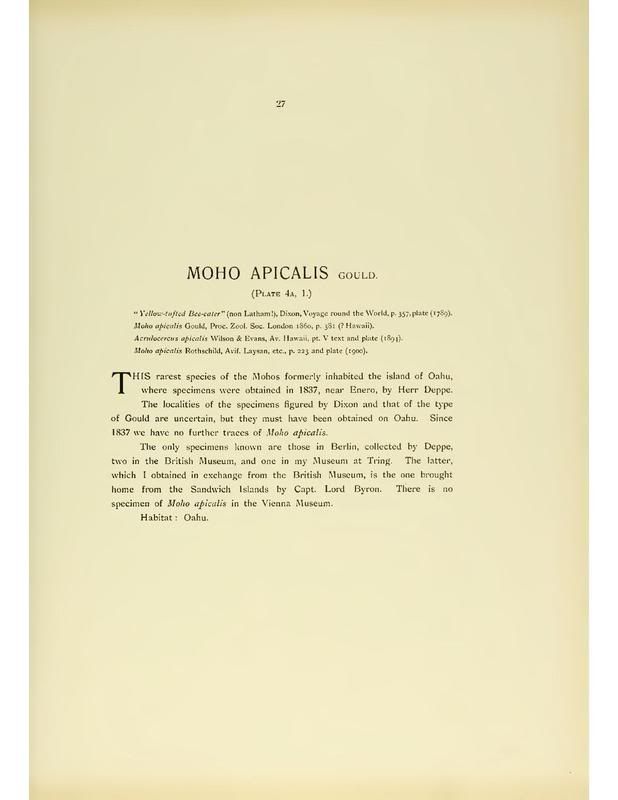

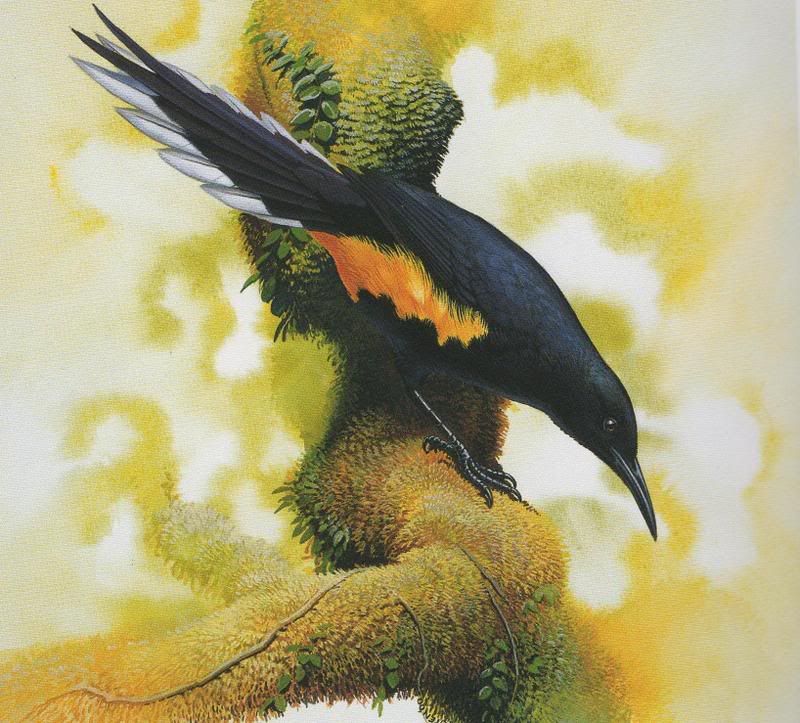

O`AHU 'O'O (Moho apicalis) Ex Formerly Endemic to O'ahu. Last seen in 1837. The Hawaiian name 'O'O was an impression of the birds loud echoing call, "oh-oh". The only O'o species on O'aho, nothing is known of its behavior or lifestyle. A large glossy black species with bright yellow undertail forming an upright V onto the flanks. The tail was long with black and white under-feathers and black upper-feathers. The tip was white and rather ragged-looking. Thigh feathers were black. The bill was dark and slightly decurved. Sexes alike. (c.12 inches) Probably became extinct as a result of disease and predation, as well as habitat loss. Calls and Song: Presumably similar to 'O'o on other Islands.  |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 5:21:11 GMT

EXTINCT Last seen 1837 OAHU O'O Moho apicalis The Oahu O'O (Moho apicalis) was last collected in 1837, and is one of the rarest Hawaiian birds in museum collections. Despite the cultural importance of the ''O''o as a source of yellow feathers for Hawaiian feather work, next to nothing is known about the species. According to Scott B. Wilson in his book, "Birds of the Sandwich Islands," there are only 5 specimens of the Oahu O'O in museums, two in Germany and three in Great Britain. Two were collected by Captain George Dixon in 1787, one by Bryon in 1826 and two by Deppe in 1837. According to Sanford B. Dole in his "Synopsis of the Hawaiian Birds," its native name and habits were the same as the O'O's of Hawaii island. The famous naturalist of Hawaii, George Munro wrote in his book "Birds of Hawaii," I did not collect on Oahu in the 1890's but Perkins who worked the Oahu forest very thoroughly said that this bird"was almost certainly extinct." "If the Oahu O'O had as loud a call as those of Hawaii, Kauai and Molokai it would soon betray its presence to anyone traversing the forest to any extent." This extinct bird was a nectar-feeder in the lofty branches of the forest canopy. Named after an imitation of the loud, harsh 'oh-oh' call it made. The brilliant yellow feathers were extensively used by the native Hawaiians to make royal feather work. The royal bird-catcher guild used a sticky substance spread on the branches of an ohia tree to trap this bird, plucked a few of the yellow feathers and released the bird. The Oahu O'O was a striking black, brown, white and yellow bird about 12 inches in length. Most of the plumage was sooty black, but the tail was brown with large patches of white. The two central tail feathers lacked the white tips, were narrower than the others, and tapered to end as upturned hairlike points. The sides and under tail coverts were white. Sadly only the noble spirits of these incredibly beautiful honeyeaters still fly in the forests of Oahu. www.oahunaturetours.com/oahuoo.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 5:33:46 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 5:49:13 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 12:04:39 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 16, 2008 8:58:50 GMT

Extinct birds : an attempt to unite in one volume a short account of those birds which have become extinct in historical times : that is, within the last six or seven hundred years : to which are added a few which still exist, but are on the verge of extinction (1907) |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 21:40:16 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 16, 2008 8:14:28 GMT

Image reference: 35886 Title: Loxops coccinea rufa, Myadastes obcurus oahuensis, Psittirostra psittacea Description: Hemignathus lucidus, Hemignathus ellisianus, Moho apicalis. Birds (listed from top to bottom) native to the Hawaiian Islands, many now extinct. Illustration by Julian Hume. piclib.nhm.ac.uk/piclib/www/image.php?img=81646&frm=ser&search=hume,%20julian%20pender |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 12, 2008 20:33:29 GMT

Gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 28, 2008 6:48:38 GMT

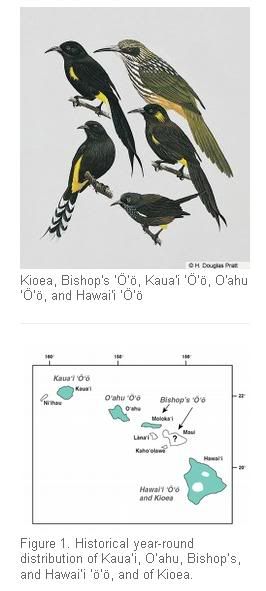

Editor's Note: This account covers the 4 species of ‘Ö‘ö in the Hawaiian Islands, plus the closely-related Kioea. Future revisions of this account may provide separate coverage for each species. This large, interesting, and diverse family of nectar-feeding honeyeaters has its center of abundance in the Australo-Papuan region and was represented in the Hawaiian Islands by 5 species: Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö (‘Ö‘ö ‘ä‘ä) on the island of Kaua‘i, O‘ahu ‘Ö‘ö on O‘ahu, Bishop’s ‘Ö‘ö on Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i ‘Ö‘ö and Kioea on Hawai‘i. The Hawai‘i ‘Ö‘ö was the first Hawaiian honey-eater discovered by westerners, described from a specimen obtained in 1779 during Captain James Cook’s third voyage; the other 4 species were not known to the scientific community until the mid- to late 1800s. The O‘ahu and Hawai‘i ‘ö‘ö and the Kioea are now definitely extinct, and the Kaua‘i and Bishop’s ‘ö‘ö are probably extinct. These medium-sized to large passerines have relatively slender, sharp, slightly down-curved, dark bills and specialized tubular tongues that function as straws for sucking nectar from many structurally different species of flowers. All 4 ‘ö‘ö have black plumage with discrete bright-yellow patches and feather-tufts, and 3 have distinctive color patterns on their graduated tail-feathers; the Kioea has a streaked head, neck, upper back, and underparts, a black mask through the eye, and uniformly colored brown wings, lower back, and long graduated tail. The bright-yellow ‘ö‘ö feathers were prized by early Hawaiians and used in making long flowing cloaks, opulent feather capes, ornate headdresses, and royal standards (kahili) of the kings and high chiefs, as well as numerous leis and other items. Yellow ‘ö‘ö feathers were also gathered into small, loosely tied bunches as tax payments by common people to the ruling class. All 5 of these honeyeaters were inhabitants of undisturbed native forests. They were highly vocal, having loud, distinct, pleasant, melodious repertoires. Only the voice of the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö was ever recorded, archived, and published, and it is probably the only Hawaiian honeyeater that has been heard by anyone now living. Except for the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö, most of our knowledge of these species is anecdotal; 3 of the 4 ‘ö‘ö species disappeared shortly after they were described. Much of the specimen material has little or no data, and only 10 O‘ahu ‘Ö‘ö and 4 Kioea study skins are known to exist in collections. Exam-ination of a series of specimens and attached labels has revealed some unpublished information, herein presented for the first time. The disappearance of Hawaiian honeyeaters was not well documented, but possible causes have been widely discussed. With the exception of hurricanes and other severe storms, negative factors contributing directly or indirectly to their extinction were related to the activities of native Hawaiians and Caucasians since their first contact with the islands. Negative factors have included destruction and modification of native forests; introduction of nonnative mammals to the islands (rats, Indian mongoose, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, domestic cats) and their impacts on native forest habitats, as well as directly on the birds themselves; introduction of nonnative birds and associated diseases; introduction of mosquitoes; and exploitation of the ‘ö‘ö for feathers. We dedicate this account to our longtime friend and colleague John L. Sincock, who died in 1991 at his home in Pennsylvania. John, a Research Wildlife Biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, studied birds in Hawai‘i (including the Leeward Islands) from 1967 until his retirement in 1984. He pioneered research on Hawaiian forest birds, particularly on Kaua‘i, and spent thousands of hours in the Alaka‘i Swamp. He found the first Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö nest in 1971 and, subsequently, 2 others. Assisted by his wife, Renate, he secured the first photographs of the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö on 31 May 1971. He subsequently took between 300 and 400 color and black-and-white photos and several hundred feet of color super-8 motion picture film of Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö in the Alaka‘i Swamp in the 1970s and made sound recordings in the early 1980s. John introduced all 4 of us to the Alaka‘i Swamp, enabling us to personally observe and hear what is believed to have been the last Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö. We rely on much of his unpublished data in this paper. In this account, if a species is not listed under a given topic, no information is known to exist on that subject for that species. Nouns in the Hawaiian language are both singular and plural. For museum abbreviations, see Appendix 1 . bna.birds.cornell.edu |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 14, 2008 6:34:55 GMT

Hawaii’s honeyeater birds tricked taxonomists DNA from old museum specimens reveals evolutionary look-alikes By Susan Milius Web edition : Friday, December 12th, 2008 Five species of Hawaiian birds have made fools of taxonomists for more than 200 years, thanks to a fine bit of evolutionary illusion-making.O‘o and kioea birds, now extinct, specialized in feeding on flower nectar using long, curved bills and split tongues tipped with brushes or fringe. Since Captain Cook’s expedition introduced the birds to western science, they have been classified in the honeyeater family with similar-looking nectar sippers living in New Guinea and Australia.DNA from museum specimens of the Hawaiian species shows that the birds weren’t a kind of honeyeater at all, according to Robert Fleischer of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Instead the Hawaiians’ resemblance to the western Pacific birds offers a new and dramatic example of how evolution within different lineages can converge on similar forms for similar jobs, he and his colleagues report online December 11 in Current Biology.O‘os and the kioea weren’t even closely related to the honeyeaters of the western Pacific, Fleischer says. The closest relatives of Hawaii’s so-called honeyeaters were waxwings, silky flycatchers and the palmchat. These kin live mostly in the Americas and use tongues of unexciting shapes to eat bugs and berries. In the United States, the cedar waxwing and the Southwest’s phainopepla may be the best-known examples.“It’s like we had this animal we always thought was a dog, and it’s turned out to be a mongoose,” Fleischer says.Genetic evidence suggests that some ancestral relative of the waxwing group arrived in Hawaii between about five and 14 million years ago, Fleischer says. Living the island life, the ancestral birds shifted to nectar feeding and evolved body forms like the honeyeaters. All the birds with similar shapes and habits looked like kin to ornithologists.Their degree of convergence is “remarkable,” in the words of Keith Barker of the University of Minnesota’s Bell Museum in Minneapolis. He’s working with DNA that uncovered another long-lost relative of the waxwings, living among southeast Asian birds. “This was shocking to us, but not nearly as startling as Fleischer's finding,” he says.Discovering the mainland connection for Hawaii’s o‘os and kioea adds yet another animal group to the list of immigrants from the Americas that colonized Hawaii, Barker says. Yet, excepting the mints and silverswords, a lot of Hawaii’s plants seem to have come from the opposite direction, from the South Pacific.While living in Hawaii, the new nectar feeders diversified into four o‘o species, each on a different island, with the kioea residing on the Big Island.Lemon- colored patches in o‘o plumage supplied brilliant yellow feathers for island royalty’s ceremonial capes and headdresses.The kioea disappeared first, during the 1850s. O‘os hung on longer. The last of the species, Kauai’s, hasn’t been seen since 1985. “I just missed it,” says Fleischer, who moved to Hawaii that year.Kioeas and o‘os deserve a family of their own, Fleischer and his colleagues contend. Thus, even before it was named, the newly christened Mohoidae became the only bird family that disappeared without a survivor in the last hundred years. www.sciencen ews.org/view/ generic/id/ 39312/title/ Hawaii%E2% 80%99s_honeyeate r_birds_tricked_ taxonomists |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 14, 2008 6:58:45 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 25, 2008 10:13:20 GMT

Hawaii's Bird Family Tree RearrangedScienceDaily (Dec. 16, 2008) — A group of five endemic and recently extinct Hawaiian songbird species were historically classified as "honeyeaters" due to striking similarities to birds of the same name in Australia and neighboring islands in the South Pacific. Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution, however, have recently discovered that the Hawaiian birds, commonly known as the oo's and the kioea, share no close relationship with the other honeyeaters and in fact represent a new and distinct family of birds—unfortunately, all of the species in the new family are extinct, with the last species of the group disappearing about 20 years ago. The findings of the study, conducted by Robert Fleischer, a molecular geneticist at Smithsonian's National Zoo and National Museum of Natural History and Storrs Olson and Helen James, both curators of birds at the National Museum of Natural History, were published in the international science journal Current Biology Dec. 11. "The similarities between these two groups of nectar-feeding birds in bill and tongue structure, plumage and behavior result not from relatedness, but from the process of convergent evolution—the evolution of similar traits in distantly related taxa because of common selective pressures," said Fleischer, lead author of the study. These five Hawaiian species of birds in the genera Moho and Chaetoptila, looked and behaved like Australasian honeyeaters of the family Meliphagidae, and no taxonomist since their discovery on Captain James Cook's third voyage to Hawaii in 1779 has ever classified them as anything else. However, there has been no rigorous assessment of their relationships using molecular data—until now. Smithsonian scientists obtained DNA sequences from museum specimens of Moho and Chaetoptila that had been collected in Hawaii 115-158 years ago. Analyses show that these two Hawaiian genera descended from a common ancestor. Surprisingly, however, the analyses also revealed that neither genus is a meliphagid honeyeater, nor even in the same part of the evolutionary path of songbirds as meliphagids. Instead, these Hawaiian birds are divergent members of a group that includes deceptively dissimilar families of songbirds (waxwings, neotropical silky flycatchers and palm chats). The researchers have placed these birds in their own new family, the Mohoidae. "This was something that we were not expecting at all," said Fleischer. "It's a great example of how much we can learn about systematics and evolution by applying new technologies like ancient DNA analysis to old museum specimens." A DNA rate calibration suggests that these Hawaiian taxa diverged from their closest living ancestor 14-17 million years ago, coincident with the estimated earliest arrival of a bird-pollinated plant lineage in Hawaii. Convergent evolution is illustrated well by nectar-feeding birds, but the morphological, behavioral and ecological similarity of Moho and Chaetoptila to the Australasian honeyeaters makes these groups a particularly striking example of the phenomenon. All five members of the family Mohoidae were medium-sized songbirds with slender, slightly downward curved bills with unique scroll-edged and fringed tongues, making them very specialized nectar-feeding birds. They inhabited undisturbed forests on most of the main Hawaiian islands. Although the cause for the extinction of the Mohoidae species is not definitely known, disease, human development and introduced species like mosquitoes, mongooses and rats are thought to play a significant role. The last member of the family Mohoidae to be positively identified was a Kauai o'o (Moho braccatus) in the Alakai Swamp on Kauai in 1987. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/12/081211121827.htm

|

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Nov 28, 2015 20:28:21 GMT

"Living Things Vanished from the Earth (in Japanese)" by Toshio Inomata (1993) |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 19, 2016 10:34:05 GMT

|

|