|

|

Post by Melanie on May 16, 2005 13:29:17 GMT

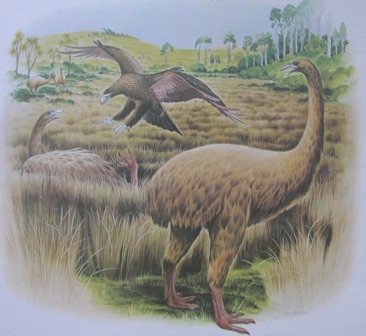

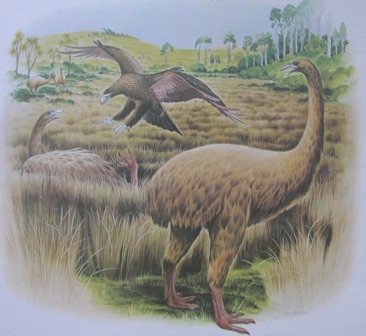

Haast's Eagle Haast's eagle was the largest eagle ever to have lived. Any larger, and it would not have been able to fly. It was also unusual because it was the top predator in a unique eco-system or food chain - one which was made up of only birds. Bones of the eagle have been found in more than 50 places, mostly in the east and south of the South Island. Some are estimated to be only 500 years old, showing that eagles and humans were alive together. Other bones are up to 30,000 years old. Julius von Haast, first director of the Canterbury Museum, was the first to "describe" bones found in the Glenmark Swamp in 1871. The most complete eagle skeleton was recovered from a cave on Mount Owen in northwest Nelson in 1990. Because eagle bones were found with moa bones in the Glenmark Swamp, it is believed that the eagle may have preyed on moas which were stuck in the swamp. Compared to other birds of prey, it had short but powerful wings for the size of its body, with a wingspan of 3 metres. This probably meant that it "flapped" rather than "soared". This also fits with the theory that Haast's eagle was a forest bird, used to flying quickly through thick vegetation. The Canterbury Plains were once a combination of forest, scrublands and grasslands, with drier forested areas than on the West Coast. Females (the larger of the eagle pair) probably weighed about 13 kilograms, and males about 10 kilograms. It also had extremely strong legs, with enormous talons of up to 60 mm long, and a vicious beak it used to tear flesh from its prey. The shape of this beak suggests that, like a vulture, Haast's eagle would feed deep inside the carcass of its prey. Haast's eagle probably hunted by watching for prey from a high perch and then swooping down onto its victim. It would use its powerful claws to grab the moa's hindquarters and then kill it by crushing the bone and puncturing the internal organs. A number of moa fossils show extensive damage from eagle claws. It is estimated that the combined strength of the legs, feet and claws would have meant that Haast's eagle would been able to kill a moa weighing 200 kilograms. Other sources of food probably included larger birds, such as duck, rail, weka and pigeon. Moa would have been killed only occasionally, as too much predation would have wiped them out earlier, and it is known that moa and eagle co-existed for at least 120,000 years. The causes of the eagle's extinction are those of other extinct species - loss of prey and habitat destruction. The coming of the Mâori to New Zealand was probably a decisive factor. Once the larger birds, including the moa, were killed off by the Mâori, Haast's eagle would have been unable to find enough large prey to keep it alive. It would have been competing with people for the same food. By the mid 14th century most of the lowland habitat of Haast's eagle would have been destroyed by fire or hunted out. Haast's eagle was still in existence when Mâori came to New Zealand, but it is not certain when it died out, although there are reports of a large bird being seen in the nineteenth century. Here is more about that species biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0030009 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 5, 2005 5:57:16 GMT

also known commonly as New Zealand Eagle

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 9, 2005 18:13:29 GMT

Pouakai, the Haast Eagle Although there were no mammalian predators in New Zealand before the advent of Homo sapiens, there were avian predators, some of which were quite extraordinary and would be considered mythical if we did not have the remains to prove their existence. One of these was the Haast eagle, the largest, most powerful, eagle the world has known, the females weighing as much as 13 kilograms and with wings spanning almost three metres. As herbivores, such as the Moa, evolved large body size, the eagle did too, allowing it to exploit a food source reserved in other lands for the great cats. Indeed the Haast eagle had talons comparable to a tiger's and was capable of killing a human. The first discovered bones of this species were found in 1871 during excavation of Moa bones at Glenmark swamp in Canterbury. They were described in 1872 by Dr Julius von Haast, first director of the Canterbury Museum, who named the bird after George Moore, owner of Glenmark Station on which so many sub fossil bird bones were found. Haast described two species of eagle, one on the basis of small bones which are now believed to represent the male. Only three complete skeletons have been found: two found late last century are in the Otago Museum in New Zealand and the Natural History Museum in London: the third, found in a cave near Nelson in 1989, is held by the National Museum in Wellington. The bones of this giant eagle are nowhere common but have been found widely in the South Island and southern half of the North Island, usually along with Moa bones in swamps and caves. However, Trevor Worthy asserts that the eagle has never been found in the North island and that all records are based on misidentifications. The youngest eagle bones found may be only 500 years old indicating that eagles and humans co-existed. Charlie Douglas in the bird section of his book describes shooting something in the late 1800s that was probably two eagles. Research by Dr. Richard Holdaway on the skeletal remains of the birds suggests that the New Zealand eagle was a forest eagle that could not soar but probably hunted like other forest eagles by perching high on a branch until a suitable prey came within range and then diving on it at speeds of up to 80 kilometers an hour. The impact, which could knock even the largest Moa off its feet, was cushioned by powerful legs. The brutal talons were then used to crush and pierce the neck and skull of the immobilised prey. The eagle and its mate could remain near the kill for several days. Like all eagles the Haast also ate carrion and preyed on trapped animals when these were available. With a life span approaching 20 years, the eagles occupied, in pairs, territories up to several hundred square kilometers. They were found mainly in the drier eastern forest during the Holocene but were more widespread in the scattered forest and scrublands of the late Otiran Glaciations 20,000 - 14,000 years ago. The Maori seemed to have called the bird Te Pouakai or Te Hokioi. Murdoch Riley in his forthcoming book on Maori bird lore says that most authorities favour Te Hokioi. Other authorities say that the bird was a very large hawk that lived on the tops of mountains, another that it stayed always in the sky and was a descendant of the star Rehua.It was regarded as the ancestor of ceremonial kites, which generally took the form of birds. Elsdon Best records that it was a legendary bird, reputed to carry off and devour men, women and children.The birds were also depicted in rock drawings. The Haast eagle succumbed to the environmental damage resulting from Polynesian colonisation. It became extinct probably several hundred years ago, along with the Moa, its main food source. Trevor Worthy says that Maori did kill them as their bones have been found in middens and fashioned into tools. nzbirds.com/Harpogornis.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 9, 2005 18:16:35 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Sept 21, 2005 11:29:31 GMT

Giant eagle had small beginnings Jan 5, 2005 New research on the world's largest ever eagle, whose fossilised remains were uncovered in New Zealand, has surprised scientists studying its DNA. The native Haast's eagle weighed 14 kilograms, had wing's spanning three metres and claws the size of a tiger's. It was New Zealand's top predator and was so powerful it dominated the food chain up until 500 years ago. It was unusual because it could kill animals up to 15 times its body size, such as giant Moa. Scientists studying the giant bird have always thought it was related to the Australian wedge-tailed eagle. But new DNA research by universities in New Zealand and at Oxford have put an end to that theory. The results found the Haast's eagle was in fact related to one of the world's smallest from Australia and New Guinea - weighing less than one kilogram. It evolved an an unprecedented scale growing 10 to 15 times in size over one million years. An unlimited food supply is thought to be responsible. When the eagles ancestor arrived in New Zealand there were no predatory mammals that scientists know of. It is thought the species died off five centuries ago, with forest fires and humans destroying its habitat and food supply. The research is set to have far reaching consequences as scientists believe DNA sampling, like that used in the case of the Haast's eagle, could re-write the research on other extinct birds and animals. Source: One News tvnz.co.nz/view/news_technology_story_skin/467281?format=htmlThe page has also a link to related video. Giant eagle had small beginnings (01:45).

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Sept 21, 2005 11:35:14 GMT

Ancient DNA Tells Story of Giant Eagle EvolutionDOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030020 Published: January 4, 2005 Copyright: © 2005 Public Library of Science. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Citation: (2005) Ancient DNA Tells Story of Giant Eagle Evolution. PLoS Biol 3(1): e20 ----------------------------------------------------------------------- The recent discovery of a Hobbit-like hominid on the Indonesian island of Flores was startling in some respects—its rather modern existence, for one—but it represents a classic case of Darwinian evolution. For reasons that are not entirely clear, when animals make their way to isolated islands, they tend to evolve relatively quickly toward an outsized or pint-sized version of their mainland counterpart. Following this evolutionary script, the Flores woman, presumably a downsized version of Homo erectus, appears to have shared her island home with dwarf elephants and giant rats. Perhaps the most famous example of an island giant—and, sadly, of species extinction—is the dodo, once found on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. When the dodo's ancestor (thought to be a migratory pigeon) settled on this island with abundant food, no competition from terrestrial mammals, and no predators, it could survive without flying, and thus was freed from the energetic and size constraints of flight. New Zealand also had avian giants, now extinct, including the flightless moa, an ostrich-like bird, and Haast's eagle (Harpagornis moorei), which had a wingspan up to 3 meters. Though Haast's eagle could fly—and presumably used its wings to launch brutal attacks on the hapless moa—its body mass (10–14 kilograms) pushed the limits for self-propelled flight. As extreme evolutionary examples, these island birds can offer insights into the forces and events shaping evolutionary change. In a new study, Michael Bunce et al. compared ancient mitochondrial DNA extracted from Haast's eagle bones with DNA sequences of 16 living eagle species to better characterize the evolutionary history of the extinct giant raptor. Their results suggest the extinct raptor underwent a rapid evolutionary transformation that belies its kinship to some of the world's smallest eagle species. The authors characterized the rates of sequence evolution within mitochondrial DNA to establish the evolutionary relationships between the different eagle species. Their analysis places Haast's eagle in the same evolutionary lineage as a group of small eagle species in the genus Hieraaetus. Surprisingly, the genetic distance separating the giant eagle and its more diminutive Hieraaetus cousins from their last common ancestor is relatively small. Without the fossils to directly determine divergence times, Bunce et al. relied on molecular dating techniques that use the rate of sequence evolution in the genes studied to establish the relative evolutionary ages of the eagles. Proposing a divergence date of roughly 0.7–1.8 million years ago, the authors acknowledge that while this is the “best available approximation of the ‘true’ date,” additional molecular data could help refine the estimate. Whatever the date of divergence, the extinct giant eagle is clearly an anomaly among the eagles studied here. The increase in body size—by at least an order of magnitude in less than 2 million years—is particularly remarkable, Bunce et al. argue, since it occurred in a species still capable of flight. The absence of mammalian competitors facilitated the evolution of much larger eagles and owls on Cuba and may have likewise precipitated the rapid morphological shift seen here. Haast's eagle, the authors write, “represents an extreme example of how freedom from competition on island ecosystems can rapidly influence morphological adaptation and speciation.” Given its similarity to the smaller Hieraaetus species, the authors recommend reclassifying the New Zealand giant as Hieraaetus moorei. This study shows how quickly morphological changes can occur in vertebrate lineages within island ecosystems. Could it be that anthropologists might some day uncover evidence of a giant version of the Flores woman? Source: biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0030020.

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Sept 21, 2005 13:03:38 GMT

From: Ancient DNA Provides New Insights into the Evolutionary History of New Zealand's Extinct Giant Eagle Michael Bunce, Marta Szulkin, Heather R. L. Lerner, Ian Barnes, Beth Shapiro, Alan Cooper, Richard N. Holdaway PLoS Biology Vol. 3, No. 1, e9 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030009 Full-textPrint PDF (3124K)Screen PDF (178K) The type species for the genus Hieraaetus is H. pennatus (Gmelin, 1788); therefore, the taxa grouping strongly with H. pennatus must remain in that genus. The close genetic relationship of H. morphnoides with H. pennatus firmly embeds this species in Hieraaetus. However, the New Guinea subspecies presently recognised as H. morphnoides weiskei is genetically, geographically, and morphologically distinct and warrants species status, which necessitates the new combination Hieraaetus weiskei (Reichenow, 1900). Harpagornis moorei is included in the clade with H. pennatus and H. morphnoides, and hence its generic assignment must reflect that. The name for the extinct Harpagornis moorei of New Zealand should therefore be amended to Hieraaetus moorei (Haast, 1872).  So it closely related to: Hieraaetus pennatus pennatusand Hieraaetus morphnoides morphnoidesAnd also but only a bit les with: Hieraaetus morphnoides weiskei |

|

|

|

Post by sordes on Sept 21, 2005 16:00:59 GMT

It is often said that the hargpagornis was the largest bird of prey (or even the largest bird) ever. But there are several birds of prey and related vultures which have today the nearly the same or the same size as Harpagornis, like the monk vulture or Steller´s sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus). The only difference is that harpagornis was much more powerfully built, similar to a south american harpy. There were much larger flying birds in the past, like ostedontornis (wingspan about 5m), giant albatrosses (ws over 4m), the giant south american terratorns with their largest member argentavis magnificiens (ws 7-8m). The difference between this birds and harpagornis was that they used their long wings like airplanes, and used warm thermics to fly, whereas harpagornis was an active flyer like a modern buzzard.

There is also a famous maori rock painting which shows a man with a killed albatross and a killed giant eagle, very probable a harpagornis.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 25, 2005 7:52:03 GMT

Alarge image than originally posted  Phalange measured from summit to articular end to point, 2.9 inches (70 cm); circumference, 3.17 inches (85 cm).  nzbirds.com/birds/haasteagle.html nzbirds.com/birds/haasteagle.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 25, 2005 7:55:34 GMT

This bird, the Hokioi, was seen by our ancestors. We (of the present day) have not seen it — that bird has disappeared now–a–days. The statement of our ancestor was that it was a powerful bird, a very powerful bird. It was a very large hawk. Its resting place was on the top of mountains; it did not rest on the plains. On the days in which it was on the wing our ancestors saw it; it was not seen every day as its abiding place was on the mountains. Its colour was red and black and white. It was a bird of (black) feathers, tinged with yellow and green; it had a bunch of red feathers on top of its head. It was a large bird, as large as a Moa. Its rival was the hawk. The hawk said it could reach the heavens; the hokioi said it could reach the heavens; there was contention between them. The hokioi said to the hawk, “what shall be your sign?” The hawk replied, “kei” (the peculiar cry of the hawk). Then the hawk asked, “what is to be your sign?” The hokioi replied, “hokioi–hokioi–hu–u.” These were there words. They then flew and approached the heavens. The winds and the clouds came. The hawk called out “kei” and descended, it could go no further on account of the winds and the clouds, but the hokioi disappeared into the heavens. “Kei” is the cry of the hawk. “Hokioi–hokioi” is the cry of the hokioi. “Hu–u” is the noise caused by the wings of the hokioi. It was recognized by the noise of its wings when it descends to earth. The bird was also depicted in rock drawings. nzbirds.com/birds/hokioi.html |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Oct 25, 2005 21:53:57 GMT

The Harpagornis or Haast's eagle was a massive New Zealand eagle. After the extinction of the teratorns, the harpigornis was the largest bird of prey in the world. It is believed that Maori called it Pouakai or Hokioi. Female Harpagornis weighed 10 to 14 kilograms (22 to 30 pounds) and males 9 to 10 kilograms. They had a wingspan of about 3 meters which is short for a bird of that weight but which allowed them to hunt in forests. It preyed on large, flightless birds species including moa up to 15 times its weight. It attacked moa at speeds up to 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph), seizing a moa by the pelvis with the talons of one foot and killing it with a blow to the head or neck with a talon of the other foot. In the absence of other large predators or scavengers, Harpagornis could have fed on a single large kill over a number of days. Early human settlers in New Zealand (Maori arrived about 1000 years ago) also preyed heavily on large, flightless birds and hunted some of them, including all the moa species, to extinction. The Harpagornis became extinct along with its prey. It may also have been hunted itself by humans: a large, fast bird of prey that specialized in hunting large bipeds may have been perceived as a threat by Maori. Until recent human colonisation, the only mammals found on New Zealand were a handful of bat species. Free from this competition, birds occupied all positions in the New Zealand animal ecology. Moa filled a grazing niche occupied elsewhere by deer or cattle, and the harpagornis occupied the same niche as carnivorous hunters such as wolves, leopards or tigers. For this reason, they have sometimes been termed leopard eagles. DNA analysis has shown that it is most closely related to the small Little Eagle and Booted Eagle, and not, as previously thought, to the large Wedge-tailed Eagle. In fact, Harpagornis is more closely related to the Little Eagle and Booted Eagle, than these are to other members of the genus Hieraaetus. Thus, Harpagornis moorei should probably be reclassified as Hieraaetus moorei pending confirmation. Harpagornis may have diverged from these small eagles as recently as 700,000 to 1.8 million years ago. Its increase in weight by 10 to 15 times in that period is the greatest and fastest evolutionary increase in weight of any known vertebrate. This was made possible by the presence of large prey and the absence of competition from other large predators. This bird was first classified by Julius von Haast, who named it Harpagornis moorei after George Henry Moore, the owner of the Glenmark Estate where the bones of the bird had been found.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 26, 2005 4:04:23 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Oct 27, 2005 17:27:46 GMT

Hi ! ... found somewhere in the internet ...  Bye Alex |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 27, 2005 22:15:55 GMT

Harpogornis atop a slain moa. From Richard Holdaway's Terror of the forests, New Zealand geographic, October/December 1989, p56 Frederick’s major achievement was the discovery and identification of harpagornis, the New Zealand eagle. On Sunday 26 March 1871, at Glenmark, the taxidermist was supervising an excavation five to six feet below the swamp. There, over an area of 30 feet square and among a quantity of moa remains, were found, in an excellent state of preservation, a few smaller bones. These - a femur, rib and two claws - Frederick at once deduced to be from a giant bird which preyed on and died with a swamp-stuck moa. Some time later, further bones from the same skeleton were discovered. library.christchurch.org.nz/Heritage/RichManPoorMan/FrederickRichardsonFuller/ |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Jan 16, 2006 12:34:56 GMT

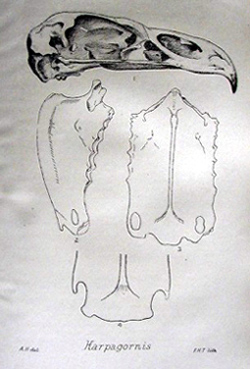

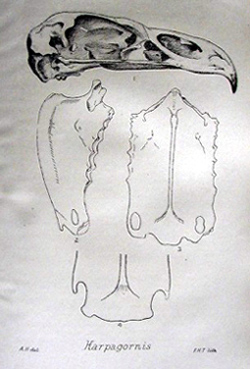

Hi ! The scull of Harpagornis moorei (wrong named in the book as Harpagornis morreri):  from 'The Origin and Evolution of Birds' by Alan Feduccia |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 31, 2006 20:32:13 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 31, 2006 20:34:27 GMT

Giant eagles not just the stuff of legends Reprinted from the University of Canterbury's "Chronicle" - 18/02/05 Gigantic eagles swooping from the skies to rescue Frodo and Sam in the Lord of the Rings film trilogy may not be just the stuff of legends and fairytales, according to research published this week in the journal PloS Biology. Dr Richard Holdaway with a moa bone, the staple diet of the Haast's eagle. (On the computer screen is an illustration of a Haast's eagle hunting moa - image courtesy of John Megahan.) Click here to view a larger version University of Canterbury senior fellow and palaeobiologist Dr Richard Holdaway is among a group of researchers from New Zealand and the UK who have shed new light on the evolution of the now extinct giant eagle that once ruled the skies over New Zealand. The enormous Haast's eagle dominated its environment. Weighing in at between 10 and 14kgs, it was 30-40% heavier than the largest living bird of prey around today, the harpy eagle of Central and South America, and was approaching the upper weight limit for powered flight. Led by Professor Alan Cooper from Oxford University's Ancient Biomolecules Centre, the New Zealand researchers extracted DNA from fossil eagle bones dating back about 2000 years. Christchurch evolutionary molecular biologist Dr Michael Bunce, now based at McMaster University, Canada, who was part of the Oxford team that carried out the DNA analysis, said when they began the project it was to prove the relationship of the extinct Haast's eagle with the large Australian wedge-tailed eagle. "But the DNA results were so radical that, at first, we questioned their authenticity," he said. The results showed that the New Zealand giant was in fact related to one of the world's smallest eagles - the little eagle from Australia and New Guinea, which typically weighs less than one kilogram. "Even more striking was how closely related genetically the two species were. We estimate that their common ancestor lived less than a million years ago. It means that an eagle arrived in New Zealand and increased in weight by 10 -15 times over this period, which is very fast in evolutionary terms. Such rapid size change is unprecedented in birds and animals," added Dr Bunce. UC's Dr Holdaway, co-author of the highly-acclaimed The Lost World of the Moa, was extensively involved in the interpretation of the results and the writing of the paper. Speculating on why Haast's eagle grew so quickly to such vast proportions Dr Holdaway said: "The size of available prey and the absence of other predators are, we think, the key factors driving the size increase. The eagles would have been able to feed unhindered on their kill." Haast's eagle is the only eagle known to have been the top predator in a major terrestrial ecosystem. They hunted moa which could weigh up to 200kg. With a truncated wingspan of around three metres for flying under the forest canopy, the eagles struck their prey from the side, tearing into the pelvic flesh and gripping the bone with claws the size of a tiger's paw. Once caught, the moa would be killed by a single strike to the head or neck from the eagle's other claw. The scientists believe the eagle died out within two centuries of human settlement of New Zealand. Forest fires destroyed its habitat and humans exterminated its food supply. There is some evidence to suggest the eagles were hunted too. "There are so many unanswered questions about our biological past that ancient DNA can help provide answers to, and it's great to see New Zealand's birds being the focus of this international research," Dr Holdaway said. www.nzine.co.nz/features/gianteagle.html?PTPFrom=%2F |

|

|

|

Post by sordes on Feb 10, 2006 20:01:12 GMT

Harpagornis was really large, but not 30-40% heavier than the largest living bird of prey. Females of Steller´s sea eagle can reach a weight of 7-9kg, not much smaller than a male Harpagornis.

|

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Feb 12, 2006 19:18:46 GMT

Haast’s eagle, New Zealand giant eagleHarpagornis moorei  Haast’s eagle was the largest eagle ever to have lived and is the only eagle in the world ever to have been top predator of its ecosystem. StatisticsWeight: approximately 10-13kg; Wingspan: up to 2.6m for a large female. Physical DescriptionHaast’s eagle was a large eagle with a low, narrow skull and an elongated beak. The males were smaller than the females. It had relatively short wings for its size: these were designed for flapping flight not for soaring. Its wing structure also helped it to catch and subdue prey as large as, or larger than, the eagle itself, and was better suited for fast, manoeuvrable flight in dense forest. Because of its large size, Haast’s eagle was approaching the upper limit of size for flapping flight – if it got any bigger it would have had to rely on gliding. Its leg bones were better suited for perching or for gripping prey than for walking about on the ground. The structure of the foot and length of the talons meant that Haast’s eagle could apply much greater force with its feet than other birds of prey. The talons could stab several centimetres into flesh, and often punctured bones as well. DistributionFossils have been found all across South Island, New Zealand. HabitatFossil evidence shows that the areas where the Haast’s eagle lived were covered in forest and shrublands, as well as in the grasslands on river floodplains. DietIt preyed upon flightless birds, including various species of moa. Palaeontologists believe that its prey ranged in size from 1kg to over 200kg in weight - the latter being the giant moa (Dinornis giganteus). The most common prey was likely the flightless Finsch’s duck (Euryanas finschi), now extinct. As New Zealand lacked any terrestrial mammals, the Haast’s eagle was top predator. BehaviourThe Haast’s eagle is unusual, because of the sheer size of many of its prey. Most eagles kill animals that are less than their own body weight. This is because they have to be able to fly while carrying their kill. As there were no terrestrial predators bigger than a tuatara (a reptile about 500g-1kg in weight) in New Zealand, the Haast’s eagle only had to defend its meal from other eagles, and thus didn’t have to carry it to a safe place to eat it. The eagle attacked a variety of flightless birds found in New Zealand including the now extinct moas. It would launch itself from a high perch onto its prey and strike at the moa’s side. Its large talons grasped the hindquarters of the moa, and killed it by inflicting deep crushing wounds that caused massive internal bleeding. The moa perished from shock or blood loss. Over a dozen fossil moa have been found with gashes and punctures from eagle claws on their pelvis. Fossil moa bones show us how the eagle used its beak after it had caught its prey: it used the elongated beak to open up the carcass and reach inside to grab mouthfuls of organs such as the kidneys. When people arrived in New Zealand, the eagle may have mistaken them for moa and thus attacked and eaten them. ReproductionNo fossils of eggs or chicks have been found. Conservation statusThey are extinct. NotesPictures of Haast’s eagle are found in rock paintings drawn in the 13th and 14th century - not long after the Polynesians first discovered New Zealand. RecordsAt 10-13kg and with a 2.6m wingspan, the Haast’s eagle is the largest ever eagle. HistoryThe Haast’s eagle was found all over South Island during the Pleistocene, but was mostly restricted to the south and east of South Island after the end of the Ice Age. The arrival of people in New Zealand had unfortunate consequences for the eagle: by 1400 AD, most of the forest habitat it used had been cleared by fire, and most of the large flightless birds that it ate had been hunted to extinction. The Haast’s eagle was likely extinct by 1400 AD, although there are a few 19th century accounts of sightings of very large birds of prey in mountainous areas. Closest relativeIts living relatives are eagles in the genus Aquila. The closest relative is probably the Australian wedge-tailed eagle, Aquila audax. Source: www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/3044.shtml

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 15, 2006 14:45:10 GMT

Harpagornis moorei Haast 1872 Holocene of New Zealand Primary materials: Holotype: nearly complete skeleton Pierce Brodkorb, Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes) Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences 8 (1964): 195-335 www.ornitaxa.com/SM/Fossil/FossilAccipi.htm |

|