|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 26, 2008 12:37:46 GMT

ScienceDaily (Jul. 5, 2007) — The ancient gray wolves of Alaska became extinct some 12,000 years ago, and the wolves in Alaska today are not their descendents but a different subspecies, an international team of scientists reports in the July 3 print edition of the journal Current Biology. The scientists analyzed DNA samples, conducted radio carbon dating and studied the chemical composition of ancient wolves at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. They then compared the results with modern wolves and found that the two were genetically distinct. "The ancient Alaskan gray wolves are all more similar to one another than any of them is to any modern North American or modern Eurasian wolf," said study co-author Blaire Van Valkenburgh, UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. The ancient gray wolves lived in Alaska continuously from at least 45,000 years ago --probably earlier, but radio carbon dating does not allow for the establishment of an earlier date -- until approximately 12,000 years ago, Van Valkenburgh said. The ancient gray wolves were not much different in size from modern Alaskan wolves, although their massive teeth and strong jaw muscles were larger. They were capable of killing large bison, Van Valkenburgh said. The ancient wolves suffered many broken teeth and tooth fractures, she said. Van Valkenburgh has also studied tooth fractures in ancient animals at Los Angeles' Rancho La Brea Tar Pits and in modern lions, tigers, leopards, puma and wolves. The ancient large mammals broke their teeth frequently when they ate, crunching the bones of their prey much more often than their modern counterparts. Why? "Because they were hungry, which may have been because it was difficult to catch and hold onto prey when there was much competition and theft among carnivores, forcing them to eat quickly," said Van Valkenburgh, who won a UCLA distinguished teaching award in June. "They were probably living at such high densities that we have difficulty even imagining, with frequent encounters between carnivores." The ancient wolves' competitors for food included lions, saber-toothed cats and enormous short-faced bears, she said. The saber-toothed cat and other large mammals became extinct about 10,000 to 11,000 years ago when their prey disappeared due to factors that included human hunting and dramatic global warming at the end of the Pleistocene, Van Valkenburgh said. Prior to the new research, it was not known whether today's gray wolves in Alaska and elsewhere descended from ancient gray wolves that roamed those areas in the Pleistocene or whether there was an extinction or near extinction of the gray wolves from northern North America. Does the research have implications for global warming today? "When environmental change happens very rapidly, animals cannot adapt, especially when the few places for them to move as habitats shrink; they are more likely to go extinct," Van Valkenburgh said. "It was a rapid climate change in the late Pleistocene." The research was federally funded by the National Science Foundation. The lead author on the research, Jennifer Leonard, earned her doctorate from UCLA and is now on the faculty of Sweden's Uppsala University. She studied the DNA of more than a dozen wolves that lived 12,000 to 45,000 years ago. Other co-authors are Carles Vilà, a faculty member at Uppsala University; Kena Fox-Dobbs and Paul Koch from the department of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz; and Robert Wayne, a UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. Adapted from materials provided by University of California - Los Angeles. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/07/070704144900.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 26, 2008 12:43:55 GMT

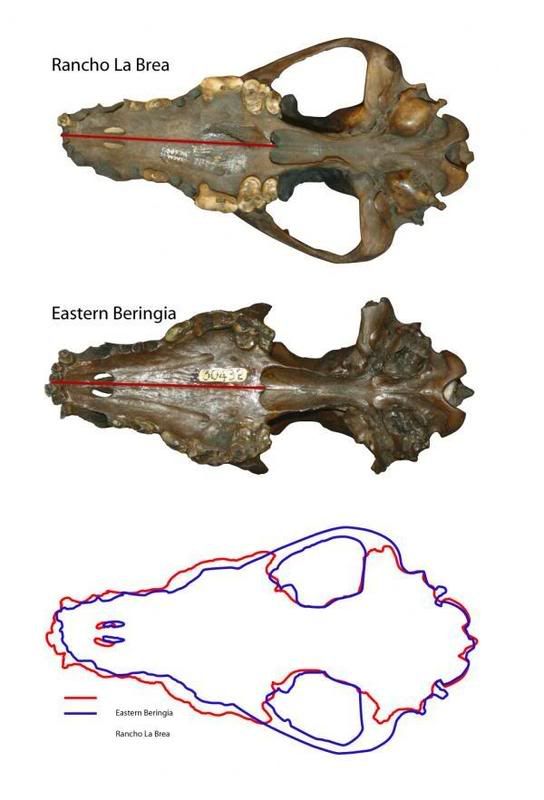

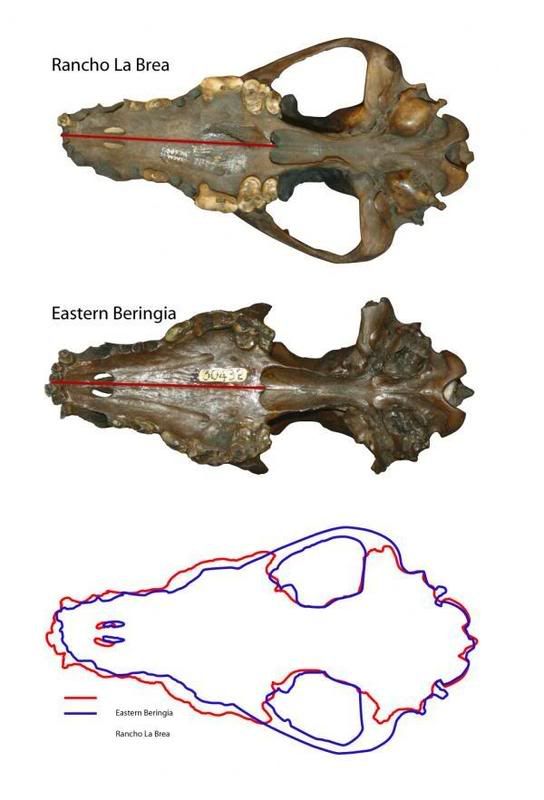

Re: Ice Age Extinction Claimed Highly Carnivorous ScienceDaily (Jun. 22, 2007) — The extinction of many large mammals at the end of the Ice Age may have packed an even bigger punch than scientists have realized. To the list of victims such as woolly mammoths and saber-toothed cats, a Smithsonian-led team of scientists has added one more: a highly carnivorous form of wolf that lived in Alaska, north of the ice sheets.  Photographs of Pleistocene wolf skulls from Rancho La Brea, California (above) and Alaska (middle). Bottom panel shows overlay of the outlines of the two skulls illustrating that although they are the same length, their shape is different-the wolf skull from Alaska is wider, and therefore those wolves had greater biting power. (Credit: Blaire Van Valkenburgh, University of California, Los Angeles) Wolves were generally thought to have survived the end-Pleistocene extinction relatively unscathed. But this previously unrecognized type of wolf appears to have vanished without a trace some 12,000 years ago. The study combined genetic and chemical analyses with more conventional paleontological study of the morphology, or form, of the fossilized skeletal remains. This multifaceted approach allowed the researchers to trace the ancient wolves' genetic relationships with modern-day wolves, as well as understand their role in the ancient ecosystem. "Being able to say all of those things--having a complete picture--is really unusual," said lead author Jennifer Leonard, a research associate with the Smithsonian Genetics Program, and currently at Uppsala University in Sweden. The researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA from the fossil wolf bones preserved in permafrost and compared the sequences, called haplotypes, with those of modern-day wolves in Alaska and throughout the world. The fossils showed a wide range of haplotypes--greater in fact than their modern counterpart--but there was no overlap with modern wolves. This was unexpected. "We thought possibly they would be related to Asian wolves instead of American wolves because North America and Asia were connected during that time period. That they were completely unrelated to anything living was quite a surprise," Leonard said. The result implies that the Alaskan wolves died out completely, leaving no modern descendents. After the extinction, the Alaskan habitat was probably recolonized by wolves that survived south of the ice sheet in the continental United States, Leonard said. The ancient Alaskan wolves differed from modern wolves not only in their genes, but also in their skulls and teeth, which were robust and more adapted for forceful bites and shearing flesh than are those of modern wolves. They also showed a higher incidence of broken teeth than living wolves. "Taken together, these features suggest a wolf specialized for killing and consuming relatively large prey, and also possibly habitual scavenging," Leonard said. Chemical analyses of the bones back up this conclusion. Carbon and nitrogen isotope values of the Alaskan wolf bones are intermediate between those of potential prey species--mammoth, bison, musk ox and caribou--suggesting that their diet was a mix of these large species. The cause of Pleistocene extinction (called the "megafaunal" extinction because of the large size of many of its victims) is controversial. It has been variously blamed on human hunting or climate change, or on a combination of factors as the Ice Age waned. For the specialized Alaskan wolves, the story is perhaps less complicated. "When their prey disappeared, these wolves did as well," Leonard said. But the results of this study also imply that the effects of the extinction were broader than previously thought. "There may be other extinctions of unique Pleistocene forms yet to be discovered," she added. This research will be published in the June 21 online issue of Current Biology. Authors: Jennifer A. Leonard, Genetics Program/Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, and Uppsala University, Sweden; Carles Vilà, Uppsala University; Kena Fox-Dobbs, University of California, Santa Cruz; Paul L. Koch, University of California, Santa Cruz; Robert K. Wayne, University of California, Los Angeles; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, University of California, Los Angeles. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/06/070621123444.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 28, 2008 16:06:23 GMT

Extinct Wolf Remains Found in Alaska Jennifer Viegas with Discovery News tells us about an article in Current Biology that describes a massive, monstrous wolf that roamed in Alaska until twelve thousand years ago. Imagine a wolf with teeth that shreds flesh easily, and cracks the bones of any animal it preys upon. It is possible that this wolf was so vicious because of the competition with other fierce predators in that era: saber tooth cats, bears, and lions. This wolf looked very similar to the gray wolf of today, but with some minor differences. The head of the wolf that lived twelve thousand years ago would have been a little wider than the wolf we know today, while the snout would have been shorter. Although the current day wolf and the extinct wolf have a couple distinct differences, Blaire Van Valkenburgh, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the Los Angeles University of California, states that the wolf is still "clearly recognizable as Canis Lupus." The physical differences are rather small. The largest and most distinctive difference between the two wolves is the genetic markers. DNA from twenty of the extinct wolves' remains was studied by scientists. The DNA was then compared to the DNA of four hundred thirty six modern day wolves. When the comparison was completed, it was found that the extinct Alaskan wolf most closely resembled ancient Czech, Siberian Russian and Ukrainian wolves. Van Valkenburgh stated that "this confirms previously held ideas that gray wolves invaded North America from the Old World via the Beringian land bridge (that once joined Alaska and Siberia) and traveled south of the ice sheets prior to the last glacial maximum 18,000 years ago". Scientists now believe that this is proof that the land was all joined in prehistoric times. In addition to the DNA comparisons performed, scientists compared the teeth wear of the extinct wolves to that of three hundred thirteen modern North American wolves. The ancient Alaskan wolves ate similar to spotted hyenas of today: they gnawed the bones, and cracked them with its "cheek teeth". www.associatedcontent.com/article/289694/extinct_wolf_remains_found_in_alaska.html |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 3, 2009 23:48:04 GMT

Bone-crushing super-wolf went extinct during last Ice Age Category: Animals • Mammals • Palaeontology Posted on: May 3, 2009 10:00 AM, by Ed Yong Being confronted with a pack of wolves is bad enough, but if you happened to be in Alaska some 12,000 years ago, things would be much, much worse. Back then, the icy forests were patrolled by a sort of super-wolf. Larger and stronger than the modern gray wolf, this beast had bigger teeth and more powerful jaws, built to kill very large prey. The gray wolf - smaller than the Beringian variety, and with weaker jawsThis uber-wolf was discovered by Jennifer Leonard and colleagues from the University of California, Los Angeles. The group were studying the remains of ancient gray wolves, frozen in permafrost in eastern Beringia, a region that includes Alaska and northwest Canada. These freezer-like conditions preserved the bodies very well, and the team found themselves in a unique position. They could not only analyse the bones of an extinct species, but they could extract DNA from said bones, and study its genes too. For their first surprise, they found that these ancient wolves were genetically distinct from modern ones. They analysed mitochondrial DNA from 20 ancient wolves and none of them was a match for over 400 modern individuals. Today's wolves are clearly not descendants of these prehistoric ones, which must have died out completely. The two groups shared a common ancestor, but lie on two separate and diverging branches on the evolutionary tree. The genes were not the only differences that Leonard found. When she analysed the skulls of the Beringian wolves, she found that their heads were shorter and broader. Their jaws were deeper than usual and were filled with very large carnassials, the large meat-shearing teeth that characterise dogs, cats and other carnivores (the group, not meat-eaters in general). This was the skull of a hypercarnivore, adapted to eat only meat and to kill prey much larger than itself using bites of tremendous force. Leonard even suggests that the mighty mammoths may have been on their menu. The eastern Beringian wolf was a formidable hunter that could also turn to scavenging - just like modern hyenas.Once prey was dismembered, the wolves would have left no bones to waste. With its large jaws, it could crush the bones of recent kills, or scavenge in times between hunts. Today, spotted hyenas lead a similar lifestyle. The wolves' teeth also suggest that bone-crushing was par for the course. The teeth of almost all the specimens showed significant wear and tear, and fractures were very common. Their powerful jaws allowed the Beringian wolves to quickly gobble down carcasses, bones and all, before having to fend off the competition. And back then, the competition included many other fearsome and powerful hunters, including the American lion and the short-faced bear, the largest bear to have ever lived. Leonard suggests that the ancestor of today's gray wolf reached the New World by crossing the Bering land bridge from Asia to Alaska. There, it found a role as a middle-sized hunter, sandwiched between a smaller species, the coyote, and a larger one, the dire wolf. When the large dire wolves died out, the gray wolf split into two groups. One filled the evolutionary gap left behind by the large predators by evolved stronger skulls and teeth. The other carried on in the 'slender and fast' mold. The extinct super-wolf would have been able to hunt prey even larger than this bison.But in evolution, the price of specialisation is vulnerability to extinction. When its large prey animals vanished in the Ice Age, so too did the large bone-crushing gray wolf. Its smaller and more generalised cousin, with its more varied diet, lived to hunt another day. Similar things happened in other groups of meat-eaters. The American lion and sabre-toothed cats went extinct, but the more adaptable puma and bobcat lived on. The massive short-faced bear disappeared, while the smaller and more opportunistic brown and black bears survived. Leonard's findings suggests that the casualties of the last Ice Age extinction were more numerous than previously thought. What other predators still remain to be found in the permafrost? Reference: Leonard, Vila, Fox-Dobbs, Koch. Wayne & van Valkenburgh. 2007. Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph. Curr Biol doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072 scienceblogs.com/notrocketscience/2009/05/bone-crushing_super-wolf_went_extinct_during_last_ice_age.php |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Apr 20, 2018 12:56:55 GMT

Leonard, Jennifer A. et al. (2007). Megafaunal Extinctions and the Disappearance of a Specialized Wolf Ecomorph. Current Biology 17(13): 1146-1150. [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Apr 25, 2018 9:43:40 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Apr 25, 2018 11:25:18 GMT

I am currently thinking to move this thread to Border extinctions. Or is there any evidence that this species survived the ice age?

|

|