|

|

Post by Melanie on Mar 23, 2005 19:54:24 GMT

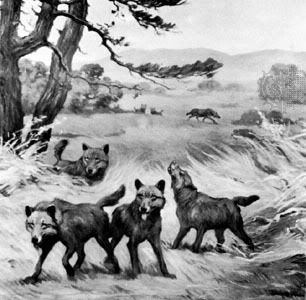

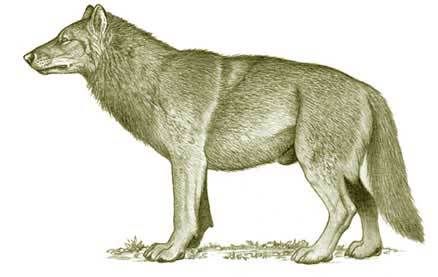

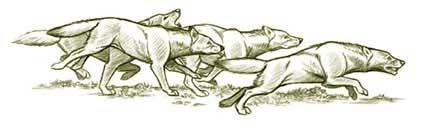

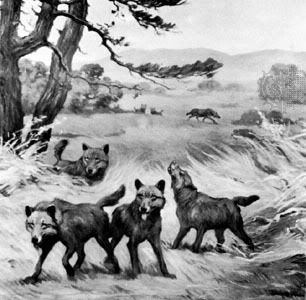

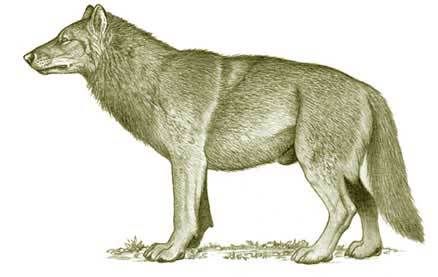

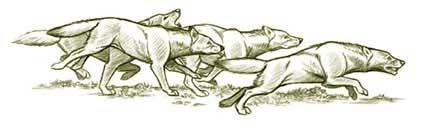

Another species which i would like to have back: DIRE WOLF Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Canidae Genus: Canis Species: dirus Physical Appearance: 5 feet long 110 pounds. Contrary to popular myth they were only slightly larger than the modern gray wolf (Canis lupus), with the exception of their teeth. They also had short but sturdier legs than the gray wolf. Habits and Reproduction: Geographic Range: North & South America** during the Pleistocene Epoch (Ice Age). Biome: Habitat: Unknown Diet: Bison, Horse, Sloth** IUCN Status: EXTINCT Threats to Survival: Elements, Lack of Food, Environmental hazards (tar pits) PROTECTION: N/A The dire wolf was a large canine that exhibited hyena like characteristics. Like the hyena, the dire wolf hunted and scavenged for food. Researchers suspect that dire wolves, due to their scavenging nature, scattered the bones of animals they killed or that were killed by other prey. The dire wolf was not quite like any animal we have today. It was similar in overall size and mass to a large modern gray wolf. (A popular misconception is that dire wolf dwarfed the modern day grey wolf) It was about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long and weighed about 50 kilograms (110 pounds) on average. The dire wolf looked fairly similar to the modern gray wolf; however, there were several important differences. The dire wolf had a larger, broader head and shorter, sturdier legs than its modern relative. The teeth of dire wolf much larger and more massive than those of the gray wolf. The brain case of the dire wolf is also smaller than that of a similarly-sized gray wolf. The fact that the lower part of the legs of the dire wolf are proportionally shorter than those of the gray wolf, indicates that the dire wolf was probably not a good a runner as the gray wolf. Many paleontologists think that the dire wolf may have used its relatively large, massive teeth to crush bone. This idea is supported by the fact that dire wolf teeth frequently have large amounts of wear on their crowns. Several people have suggested that dire wolves may have made their living in similar ways to the modern hyenas. Wolves and coyotes are relatively common large carnivores found in Ice Age sites. In fact, several thousand dire wolves have been found in the asphalt pits at Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles, CA. The coyote, gray wolf, and dire wolf have all been found in paleontological sites in the Midwestern U.S. The first specimen of a dire wolf was found at near Evansville, Indiana. Clark Kimberling of the University of Evansville has traced the very interesting history of this specimen. www.wolfsource.org/ |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Aug 2, 2005 23:52:56 GMT

Habitat: Extinct. Remains found in Ice Age paleontology sites. The remains of over 3600 dire Wolves have been found in the tar pits at Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles, California, in the United States, Specimens have also been found in the Midwestern United States. Characteristics: The dire Wolf was similar in overall size and mass to a large modern Gray Wolf. This means it was about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long and weighed about 50 kilograms (110 pounds) on average. The dire Wolf looked fairly similar to the modern Gray Wolf; however, there were several differences. The dire Wolf had a larger head and shorter, stronger legs than the Gray Wolf. The teeth of dire Wolf were much larger than that of Gray Wolves. Many paleontologists believe the dire Wolf may have used its powerful jaws and teeth to crush bone. This theory is supported by the fact that the teeth of fossil specimens often have much wear on the crowns. Some have suggested that dire Wolves may have made lived much like hyenas do today by scavenging remains. The genus Canis underwent a mixed fate at the end of the Pleistocene. Gray Wolves and coyotes survived the extinction that occurred 9,000 to 10,000 years ago. Dire Wolves, however, didn't make it. It's thought that dire Wolves depended on scavenging remains of large herbivores that lived during the last Ice Age. When these animals were lost so were the dire Wolves. Scientists don't know if this is the case, however. But the fact that dire Wolves had shorter legs than Gray Wolves, might have meant they were slow runners and not as adept at catching prey.  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Aug 3, 2005 0:00:57 GMT

There was a subspecies Canis dirus guildayi and the following species were perhaps all synonyms of Canis dirus

Canis primaevus Leidy, 1854 (nomen nudum?)

Canis dirus Leidy, 1858

Canis indianensis Leidy, 1869

Canis mississippiensis Leidy, 1876

Canis lupus Linnaeus; Cope & Wortham, 1884

Canis dirus Leidy; Merriam, 1912

Canis ayersi Sellards, 1916

Aenocyon dirus (Leidy); Merriam, 1918

Aenocyon ayersi (Sellards); Merriam, 1918

Canis (Aenocyon) ayersi Sellards; Simpson, 1929

Canis (Aenocyon) dirus Leidy; Stock, 1946

Canis ayersi Sellards; Weigel, 1962

Canis dirus Leidy; Kurtén & Anderson, 1972

Canis dirus Leidy; Martin, 1974

Canis dirus Leidy; Nowak, 1979

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Aug 3, 2005 0:37:37 GMT

(1) Canis dirus (dire wolf, n = 25) was widespread across North America below the subarctic (Dundas, 1999) and is the most common of the RLB canids (Stock and Harris, 1992, pp. 27). Their relative abundance and low levels of canine dimorphism are suggestive of a pack-based, monogamous social structure similar to that of living wolves (Canis lupus) (Van Valkenburgh and Sacco, 2002). However, C. dirus was larger than modern timber wolves with a broad head and massive dentition more similar to modern hyenas than to hunting canids (Van Valkenburgh and Ruff, 1987), supporting early speculation that C. dirus was an adept scavenger (Merriam, 1912; Matthew and Stirton, 1930) and possibly accounting for the absence of true hyenas at RLB. The RLB subspecies Canis dirus guildayi had significantly shorter limbs than nominate C. dirus east of the continental divide; thus, RLB specimens were also less cursorial (Kurte´n, 1984). www.anthro.utah.edu/PDFs/Papers/jbcLaBrea.pdfRLB = Rancho La Brea |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Aug 3, 2005 0:47:18 GMT

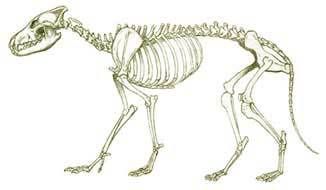

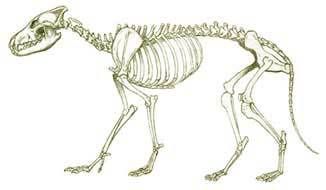

Dire Wolf skeleton in comparism. Here is a skeleton of a modern wolf  |

|

|

|

Post by Bucardo on Nov 7, 2005 17:16:56 GMT

The Wikipedia says that there are bones of Canis dirus of only 4000 years ago, discovered on the Ozark Plateau, in Arkansas. Somebody have more information about these findings?

|

|

|

|

Post by sordes on Nov 10, 2005 16:30:22 GMT

There is also a dire-wolf-skeleton in the paleontological museum of Tübingen. It is surprisingly small.

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Apr 21, 2007 13:05:38 GMT

moved to border extinctions as there is still the statement that it may have survived until 4000 BC.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2008 7:52:51 GMT

moved to border extinctions as there is still the statement that it may have survived until 4000 BC. The Dire Wolf (Canis dirus) is an extinct member of the genus Canis (which contains the other wolves, the Coyote, jackals, and the other canines), and was most common in North America during the Pleistocene. Although it was closely related to the Gray Wolf, it was not the direct ancestor of any species known today. The Dire Wolf co-existed with the Gray Wolf in North America for about 100,000 years. They were one of the abundant Pleistocene megafauna—a wide variety of very large mammals that lived during the Pleistocene. Approximately 10,000 years ago, the Dire Wolf became extinct along with most other North American megafauna. The first specimen of a Dire Wolf was found by Francis A. Linck at the mouth of Pigeon Creek along the Ohio River near Evansville, Indiana in 1854, but the vast majority of fossils recovered have been from the La Brea Tar Pits in California. Contents [hide] 1 Characteristics 2 Evolution and extinction 3 Fossil record 4 Evansville Dire Wolf 5 See also 6 References 7 External links [edit] Characteristics The Dire Wolf was slightly larger than the Gray Wolf. It averaged about 1.5 metres (5 feet) in length and weighed about 50 kilograms (110 pounds) Though large specimens may have weighed as much as 80kg (175 pounds).1 Despite superficial similarities in appearance, there were significant differences between the two species. The legs of the Dire Wolf were proportionally shorter and sturdier than those of the Gray Wolf, which suggests that the Dire Wolf was a poorer runner, and may have scavenged for food or hunted large, slower-moving prey. The dire wolf's dentition was similar to the grey wolf's, only slightly larger. The upper carnassials had a much larger blade than that of a grey wolf, indicating greater slicing ability. It had a longer temporal fossa and broader zygomatic arches, indicating the presence of a large temporalis muscle capable of generating slightly more force than a grey wolf's. Dire wolf teeth lack the craniodental adaptations of habitual bonecrushers such as hyenas. Molars from the skulls of dire wolves found in the La Brea tar pits show wear, indicating possible bone gnawing, though the wear is not to the same extent as that found in Borophaginae teeth.[1] The Dire Wolf had a larger, broader head and smaller brain-case than that of a similarly-sized Gray Wolf, and had teeth that were quite massive. Many paleontologists think that the Dire Wolf may have used its relatively large teeth to crush bone, an idea that is supported by the frequency of large amounts of wear on the crowns of their fossilized teeth. Dire Wolf skeletons have been found bearing healed and half-healed injuries similar to the ones found on modern wolves who have been injured while hunting large prey such as bison or horses. This suggests that the Dire Wolf also hunted for large, live prey. [edit] Evolution and extinction The fossil record suggests that the genus Canis diverged from the small, foxlike Leptocyon in North America sometime in the Late Miocene Epoch 9 to 10 million years ago (Ma), along with two other genera, Urocyon, and Vulpes. Canids soon spread to Asia and Europe (8 Ma) and became the ancestors of modern wolves, jackals, foxes, and the Raccoon Dog. By 3–5 Ma, canids had spread to Africa (Early Pliocene) and South America (Late Pliocene). Their invasion of South America as part of the Great American Interchange was enabled by the formation of the Isthmus of Panama 3 Ma ago. Over the next nine million years, extensive development and diversification of the North American wolves took place, and by the Mid-Pleistocene (800,000 years ago) Canis ambrusteri appeared and spread across North and South America. It soon disappeared from North America, but probably continued to survive in South America to become the ancestor of the Dire Wolf. (However there is some evidence to suggest that the Dire Wolf may have arisen from other small South American wolves.) During the Late Pleistocene (300,000 years ago) the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) crossed into North America and the Bering Strait land bridge. By 100,000 years ago the Dire Wolf also appeared in North America (probably from South America). Starting about 16,000 years ago, coinciding with the end of the most recent Ice Age and the arrival of humans in North America, most of the large mammals upon which the Dire Wolf depended for prey began to die out (possibly as a result of climate and/or human-induced changes). Slower than the other wolf species on the continent at the time, primarily the Gray Wolf and Red Wolf, it could not hunt the swifter species that remained and was forced to subsist on scavenging. By 10,000 years ago, the large mammals and the Dire Wolf were extinct, although some fossils found in Arkansas suggest that they may have lived as a relict population in the Ozark mountains as recently as 4,000 years ago.[edit] Fossil record A display of some of the thousands of Dire Wolf skulls found in the La Brea tar pitsThe Dire Wolf is best known for its unusually high representation in the La Brea Tar Pits in California. In total, fossils from more than 3,600 individual Dire Wolves have been recovered from the tar pits, more than any other mammal species. This large number suggests that the Dire Wolf, like modern wolves and dogs, probably hunted in packs. It also gives some insight into the pressures placed on the species near the end of its existence. [edit] Evansville Dire Wolf The type specimen of the Dire Wolf was found in Evansville, Indiana in the summer of 1854, when the Ohio River was quite low. The specimen, a fossilized jawbone, was obtained by Dr. Joseph Granville Norwood from an Evansville collector named Francis A. Linck. Dr. Norwood, who at that time was the first state geologist of Illinois, sent the specimen to Joseph Leidy at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Dr. Leidy determined that the specimen represented an extinct species of wolf and published a note to that effect in November 1854. In a publication dated 1858, Leidy assigned the name Canis dirus. Dr. Norwood's letters to Dr. Leidy, as well as the type specimen itself, are preserved at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, although one of the letters indicates that the specimen was to be returned to Linck's family, as Linck himself died in August 1854. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dire_WolfIf the 4,000 yrs is incorrect then there is proof of 10,000 yrs which makes it holocene |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2008 8:10:32 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2008 8:15:50 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2008 8:24:56 GMT

At the tar pits, a dire wolf and saber-tooth cat fight over the same morsel.  Dire wolf (Canis dirus) from Rancho La Brea, Calif.; detail of a mural by Charles R. Knight, 1922.  Dire wolf. NOVA image. www.cryptomundo.com/cryptozoo-news/dire-waheela/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 26, 2008 6:01:05 GMT

Dire Wolf Canis dirus    During the last Ice Age, dire wolves were quite common in the Rancho La Brea area. In fact, more dire wolf fossils have been found during excavations than those of any other mammal species. The large number suggests that these fierce animals, similar to modern wolves and dogs, hunted in packs and may have been caught in the asphalt together while trying to feed upon other animals. This wolf is very closely related to the modern timber wolf (also found at Rancho La Brea), but had slight physical differences, such as larger teeth and shorter limbs. www.tarpits.org/education/guide/flora/wolf.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 27, 2009 19:12:25 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by argentavis on Jan 6, 2014 20:10:18 GMT

Replica of Canis dirus skull, Moscow Paleontological Museum.  |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Mar 8, 2015 13:14:19 GMT

Carlon, Burcu. (2014). Functional limb morphology of extinct carnivores Smilodon fatalis, Panthera atrox, and Canis dirus based on comparisons with four extant felids and one extant canid. Ph.D thesis, Northern Illinois University. [ Abstract] |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 26, 2015 14:55:17 GMT

Brannick, Alexandria L., Meachen, Julie A. and O’Keefe, F. Robin. (2015). Microevolution of Jaw Shape in the Dire Wolf, Canis dirus, at Rancho La Brea, pp. 23-32. In: Harris, John M. (ed.). La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas. Los Angeles, California: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series No. 42. 174 pp. |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 27, 2015 3:47:13 GMT

DeSantis, Larisa R. G., Schubert, Blaine W., Schmitt-Linville, Elizabeth, Ungar, Peter S., Donohue, Shelly L. and Haupt, Ryan J. (2015). Dental Microwear Textures of Carnivorans from the La Brea Tar Pits, California, and Potential Extinction Implications, pp. 37-52. In: Harris, John M. (ed.). La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas. Los Angeles, California: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series No. 42. 174 pp. |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 27, 2015 4:17:25 GMT

Hartstone-Rose, Adam, Dundas, Robert G., Boyde, Bryttin, Long, Ryan C., Farrell, Aisling B. and Shaw, Christopher A. (2015). The Bacula of Rancho La Brea, pp. 53-63. In: Harris, John M. (ed.). La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas. Los Angeles, California: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series No. 42. 174 pp. |

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Dec 13, 2015 0:53:52 GMT

"The Earth Extinct Fauna (in Japanese)" by Tadaaki Imaizumi (1986) |

|