|

|

Post by Bhagatí on Dec 16, 2006 21:28:53 GMT

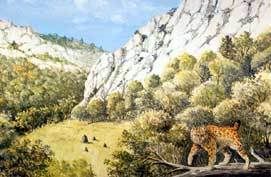

By Lynx (Lynx) pardinus spelaeus.

This extinct subspecies was lived in west Europe. In Spain and probably west France. A today's time is extincted.

Know about this subspecies - more facts.

Better is for all, their's reveal.

Single, about this subspecies isn't nothing knows.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 16, 2006 22:04:30 GMT

for starters correct spelling would be Lynx lynx spelaea or also called Lynx pardinus spelaea

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 16, 2006 22:05:21 GMT

Kurtén, B. and Granqvist, E. 1987. Fossil pardel lynx (Lynx pardina spelaea Boule) from a cave in southern France. Ann. Zool. Fennici 24:39-43. lynx.uio.no/jon/lynx/lynxibrf.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 16, 2006 22:06:38 GMT

Abstract: In the fossil deposits of the Late Pleistocene (c. 115 000–11 500 years ago), five felid species are recorded in Europe: the wildcat Felis silvestris, Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx, Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus, leopard Panthera pardus and cave lion Panthera leo spelaea. In the Holocene, Europe was colonized by F. silvestris, L. lynx and L. pardinus as well as the lion Panthera leo. The status of P. pardus in post-glacial Europe is unknown. So far, only sparse records indicate that P. pardus survived into the early Holocene. During the Late Glacial, both L. lynx and L. pardinus occurred on the Iberian Peninsula. However, from the Holocene, only the Iberian lynx is recorded in this region. There are subfossil records that indicate that L. pardinus also occurred in central and western France until c. 3000 years ago. Surprisingly, with reservations on the determination of the bones (by J. Altuna), both lions and cave lions seem to be recorded in the Iberian Peninsula in the Late Glacial. There are published records of the lion P. leo in the northern Iberian Peninsula from the early Holocene. However, its presence in Europe on the basis of subfossil records was proven initially from the Atlantic period. In Ponto-Mediterranean regions of Europe, the lion is recorded from the Atlantic to the younger sub-Atlantic. www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/jzo/2006/00000269/00000001/art00002 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 16, 2006 22:16:43 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 16, 2006 22:20:02 GMT

The lynx The lynx (Lynx spelaea) is a small carnivore that is well known throughout the Mediterranean zone. Even though it was similar in size to the Eurasian lynx, it shares the characteristics of the pardel Lynx, found in the Pyrenees. It tracked birds and small mammals, and found shelter in the cave on several occasions.   www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/arcnat/tautavel/en/env_lynx.htm www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/arcnat/tautavel/en/env_lynx.htm |

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Dec 16, 2006 23:34:47 GMT

To my knowledge, it is an extinct taxon from middle/upper Pleistocene in the lineage of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus spelaeus).

Note that it should be spelaeus in Latin grammatic accordance with the masculine noun Lynx

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 17, 2006 11:23:01 GMT

To my knowledge, it is an extinct taxon from middle/upper Pleistocene in the lineage of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus spelaeus). Note that it should be spelaeus in Latin grammatic accordance with the masculine noun Lynx During the Late Glacial, both L. lynx and L. pardinus occurred on the Iberian Peninsula. However, from the Holocene, only the Iberian lynx is recorded in this region. There are subfossil records that indicate that L. pardinus also occurred in central and western France until c. 3000 years ago. www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/jzo/2006/00000269/00000001/art00002Could this of been Lynx pardina spelaea ? |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 17, 2006 11:25:17 GMT

To my knowledge, it is an extinct taxon from middle/upper Pleistocene in the lineage of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus spelaeus). Note that it should be spelaeus in Latin grammatic accordance with the masculine noun Lynx Correct spelling was already mentioned by myself for starters correct spelling would be Lynx lynx spelaea or also called Lynx pardinus spelaea I think it would make sense to correct thread title. Will do that now. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 17, 2006 11:37:30 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Bhagatí on Dec 17, 2006 18:19:53 GMT

Thank's all - about this subspecies. Very much information and many images. Good work.    |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 17, 2006 18:23:10 GMT

My pleasure mate any time

|

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Dec 17, 2006 20:00:47 GMT

I think that it is important to mention that the bone specimens shown by Frank in Reply 4, are remains of two different individuals of Lynx pardinus spelaeus that are about 200,000-250,000 years old and came from the famous Pleistocene site called "Sima de los Huesos" (Bones Sink Hole) at Atapuerca Mts in North Spain, where they were retrieved together with bones of 23 individuals of Homo heidelbergensis (ancestor of Homo neardenthalensis), three Panthera leo spelaea, hundreds of Ursus deningeri (ancestor of the Cave Bear Ursus spelaeus), and some wolves, foxes and small carnivores. The whole area is a World Heritage Site now.

|

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Dec 17, 2006 20:08:29 GMT

Could this of been Lynx pardina spelaea ? By no means. The Middle Pleistocene form spelaeus gave origin to present (and very threatened) form Lynx p. pardinus. Holocene individuals were already modern Iberian (or Pardel) Lynx. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 17, 2006 20:54:20 GMT

so why is it called by many Lynx pardina spelaea or Lynx pardinus spelaea regarding it as a subspecies of the current modern Lynx pardina or Lynx pardinus. If its an ancestor it should be classed by all as a distinct species Lynx spelaea. Its very confusing ain't it.

|

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Dec 17, 2006 22:46:09 GMT

No. All taxa evolve and change continuously and give origing to one or more different forms and eventually to different lineages. The degree of changes define the specific or subspecific level. In this case the pardinus lineage dates back to the Lower Pleistocene, about one million years ago when a common ancestor of present Lynx lynx, became isolated in the Iberian Peninsula glacial refuge, it changed then its main prey from small cervids and hares to rabbits, an abundant and smaller prey, and became smaller itself in the line of present day Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus).

In the Middle Pleistocene, the species features were already present and the lynxes then where clearly pardinus. The fact that can be confusing to you is that Lynx pardinus has been described from a modern specimen so pardinus is the species type. Later, the Middle Pleistocene form spelaeus was described upon fossil material becoming formally a subspecies of Lynx pardinus (L. p. spelaeus) but obviously it is the ancestor of present day L. p. pardinus. They both belong to the same lineage.

The same happens to Dama dama, for instance, a species that was already well defined in the Middle Pleistocene, but the taxon living in Europe then was Dama dama clactoniana, the ancestor of modern Dama dama dama (I'm not sure about the lineage of D. d, mesopotamica, which is quite a different form, though).

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 18, 2006 8:59:45 GMT

Thanks i didn't known that Lynx pardinus spelaeus was named after Lynx pardinus pardinus. For some reason which to me is unknown i thought it was the other way.

|

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Mar 11, 2007 8:59:21 GMT

Just a reminder that L. p. spelaeus is a Middle Pleistocene form and is ancestor to modern L. p. pardinus. So no basis to mantain this thread in the Pleistocene-Holocene border extinctions part. By that time, Lynx pardinus was already the modern form.

It should be properly put in the Prehistoric Extinctions board.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Mar 11, 2007 11:02:35 GMT

The lynx-like cats are united in one genus (Lynx) with four species (lynx, pardinus, rufus, and canadensis). They occur nowadays in the northern hemisphere only: L. lynx and L. pardinus in the Palaearctic, L. rufus and L. canadensis in the Nearctic. Lynx pardinus, the Iberian lynx, was always restricted to the Iberian Peninsula south of the Pyrenees, whereas the entire remaining area in the Old World from the Atlantic coast in Europe to the Pacific Ocean in the Far East is generally regarded as the area of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx). Over such an extended range, stretching not only from west to east, but also from south to north across several climatic zones and different habitats, a differentiation on the level of subspecies is to be expected, not only due to the geographic (and ecological) distance, but also as a consequence of the repeated isolation and merging of sub-areas during the Pleistocene glaciations. The lynx distribution during the last ice age and the subsequent recolonisation of Europe has to be considered for the reconstruction of the (pre)historic range as well as for the possible differentiation of subspecies. Morphologic differences and palaeontologic and zoo-geographic considerations (MIRIC 1974, MIRIC 1978, MATJUSCHKIN 1978, WERDELIN 1981, HEMMER 1993, HEMMER 2001, MATYUSHKIN & VAISFELD 2003) are today complemented with genetic findings (HELLBORG et al. 2002, BREITENMOSER-WÜRSTEN & OBEXER-RUFF 2003, RUENESS et al. 2003), but there is no final agreement on the classification of subspecies yet. From all these works, we compile what we believe to be at present the best possible interpretation of the distribution of recent subspecies in Europe (Fig. 2.5). Fig. 2.5. Distribution of subspecies of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx): LX: lynx (nominate form, northern Europe and western Siberia), CA: carpathicus (Carpathians), MA: martinoi (Balkan), DI: dinniki (Caucasus), IS: isabellinus (Central Asia), WA: wardi (Altai), KY: kozlovi (Sajan), WR: wrangeli (eastern Siberia), ST: stroganovi (Russian Far East). Brown dots: re-introduced populations in Europe (carpathicus). The area of dinniki shows the historic range; the present distri-bution is not known, but strongly reduced and scattered. The distribution of isabellinus is proximate. Recent genetic works suggest that there is a marked differentiation within the range of lynx. In Europe, the evolutionary history of the species is distorted by human-made fragmentation and bottlenecks. Assuming that the lynx’ ecology during the late Pleistocene was not completely different from the recent species (Biology and life history), we can speculate that the recolonisation followed the expansion of forests and prey. Some regions that we today intuitively regard as "good" lynx habitat were also so during the late Pleistocene, other areas however were not. The Alps, for instance, were entirely glaciated and no living space for lynx. This mountain range was likely recolonised from both opposite ends, and the now "homogenous" habitat complex is actually the suture of two isolated late Pleistocene habitat patches, so called glacial refuges. In contrast, the Carpathians were a forest refuge during the last ice age (BURGA & PERRET 1998), and provided probably a better lynx habitat than the surrounding cold steppe plains. Parallel to the "natural" recolonisation, large scale human activities such as deforestation have had an impact on the distribution of large mammals in Europe for at least 5000 years. Human-caused extinction or near-extinction, genetic bottlenecks and recolonisation – whether natural or artificial – have altered not only the distribution, but also the genetic set-up of what may have been the original arrangement of subspecies. As an example, HEMMER (1993) proposes that lynx recolonised Scandinavia in the Holocene from the south (Denmark) and from the north (Finland). The genetic pattern of the recent lynx populations (Fig. 2.6) does not support Hemmer’s hypothesis. This is however no proof that Hemmer was wrong; the reduction of the lynx area and the subsequent recovery (JONSSON 1983) may have camouflaged phylogenetic differences within Scandinavia. Fig. 2.6. Genetic differentiation of lynx in Europe (BREITENMOSER-WÜRSTEN & OBEXER-RUFF 2003). Preliminary genetic analyses confirm the subspecies status of the lynx from the Carpathians, depict a marked difference between the Scandinavian and the Finnish-Baltic populations, and indicate – with one specimen only – the special status of the Balkan population. Considering all these aspects, we suggest to adopt the following subspecies of Lynx lynx in Europe for conservation purposes (Fig. 2.5): 1. Northern lynx (L. l. lynx), including the Fennoscandic, the Baltic and the Russian populations; 2. Carpathian lynx (L. l. carpathicus) in the Carpathian Mountains; and 3. Balkan lynx (L. l. martinoi), restricted to the south-western Balkan, mainly Albania and FYR Macedonia. Obviously, the extinct lynxes of the western Alps and the Pyrenees (referred to as L. l. spelaeus) were distinct. This form may have stretched from the Apennines (the place of origin) as far north-east as Scotland. HEMMER (2001) argued that the cave lynx was rather a species (L. spelaeus) than a subspecies, spreading from the Italian refuge after the last ice age and forming a distribution range between the Eurasian lynx (L. lynx) and the Iberian lynx (L. pardinus); but this hypothesis needs verification. www.kora.unibe.ch/en/proj/elois/online/speciesinf/subspecies/subspecies.htm |

|

|

|

Post by Carlos on Mar 11, 2007 12:14:57 GMT

It is obvious that two taxa are mixed up in this thread. The (presumed from my point of view) spelaeus subspecies of the Eurasian Lynx: Lynx lynx spelaeus (which could be or not, I don't know, a Pleistocene-Holocene border extinction, if it was a different taxa at all) and the spelaeus subspecies of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus spelaeus), which is a Pleistocene form. Then two forms: Lynx lynx spelaeus

Lynx pardinus spelaeus So two different threads are needed with correct thread names to avoid the confussion that is messing things up here. |

|