|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 17:16:08 GMT

A resident subspecies of ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis bairdii) occupied tall forests throughout Cuba, and a small population was mapped and photographed in eastern Cuba as late as 1956 (8). Fleeting observations of at least two individuals in 1986 and 1987 by several experts are widely accepted as valid (9), but repeated efforts to confirm continued existence of that population have failed (10). www.sciencemag.org/cgi/rapidpdf/1114103v1.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 17:41:04 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 17:51:58 GMT

Cuba. Distribution summarized by Gundlach (1876, 1893), Barbour (1923, 1943, 1945), Garrido (1985), and Garrido and Kirkconnell (2000). Known only from main island of Cuba, but from dispersed localities and diverse old-growth forest habitats throughout the island. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/DISTRIBUTION.html#Ivory-billed_Woodpecker_DISTRIBUTION_OUTSIDE_THE_AMERICAStinyurl.com/7qclfCuba. 1876–1893: Gundlach (1876, 1893; also cited in Garrido 1985) reported that the Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpecker was declining rapidly. 1920s: Ivory-billed Woodpeckers seen by Swedish botanist E. L. Ekman in the pine forests of Mayar, Holguin Province, e. Cuba (Barbour 1943). 1943: Ivory-billed recently shot “to pieces” at Laguna de Piedras, near Artemisa, Pinar del Río Province, w. Cuba; “the Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpecker is virtually extinct” (Barbour 1943: 86). 1945: Barbour (1945: 165) reported that “there is a chance that the Cuban Ivory-billed may exist in a remote mountain range in the northeastern part of the island in considerable numbers.” Spring 1948: John Dennis and Davis Crompton found and photographed nesting Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in e. Cuba (Dennis 1948, Crompton 1950). Spring and summer 1956: Following 3 mo of fieldwork, Lamb (1957) estimated 6 pairs of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers remained in e. Cuba. Feb 1968: An Ivory-billed Woodpecker seen 7 km north of Cupeyal along the road to Moa in ne. Cuba by Garrido (1975). 1974: O. Garrido (pers. comm. in Dennis 1979) estimated that no more than 6–8 pairs existed in Cuba in 1974. 1981: A pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers said to remain near La Melba, ne. Cuba (E. Morton in Norton 1981). 1985: Lester Short, George Reynard, and Giraldo Alayón visited the Cupeyal reserve west of the 1956 sightings and found fresh bark scaling they attributed to Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Short 1985). 1986: Alberto Estrada, Giraldo Alayón, Lester Short, Jennifer Horne, and George Reynard ob-served Ivory-billeds in the Ojito de Agua area in ne. Cuba (Short and Horne 1986, Reynard 1987, Short 1988). 1987: Short, Horne, JAJ, and several Cuban col-leagues spent 1 d in the Ojito de Agua area and observed scaling, but none seemed fresh. Mar 1988: JAJ, Ted Parker, Bates Littlehales, Bill Curtsinger, Hiram Gonzalez, Pedro Rosabal, Gir-aldo Alayón, and others spent 4 wk in the Ojito de Agua area; JAJ had a glimpse of a bird that he believed was an Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the vicinity of sightings in 1987 (Jackson 1991a), and the characteristic call notes of the Ivory-billed were heard on 8 different days by several group members. Jackson saw Ivory-billed-sized black-and-white bird for <5 s as it passed a forest opening at about 10 m with wings folded back in the characteristic glide of a woodpecker. 1991–1992: In 1991, John W. McNeely and Pitar Miranda got a glimpse of an Ivory-billed near the confluence of the Yarey and Jaguani rivers in ne. Cuba, and in early 1992 they saw fresh scaling activity in the region, but no birds (J. W. McNeely pers. comm., 17 Apr 1992). Lammertink (1992) spent 44 d in the Ojito de Agua area of ne. Cuba, where birds had been seen and heard 1986–1988; he found no evidence of Ivory-billeds. 1995: Ivory-billed Woodpecker “almost certainly extinct” (Lammertink 1995, Lammertink and Estrada 1995). topFOSSIL HISTORY The “fossil” record for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker includes considerable skeletal material of recent origin found in association with excavation of archaeological sites. Among these are sites in Illinois (Parmalee 1958), Ohio (Wetmore 1943, Goslin 1945), W. Virginia (Parmalee 1967), and Georgia (Van der Schalie and Parmalee 1960). Considering the prominent trade in Ivory-billed Woodpecker bills among Native Americans (e.g., Catesby 1731, Jackson in press), the presence of Ivory-billed mater-ial associated with archaeological sites outside of se. U.S. and Cuba cannot be taken as indicating a broader range for the species. How did this species come to be in the se. U.S. and Cuba? Presumably its ancestors arrived from n. South America or Central America, since these are the regions where Campephilus woodpeckers are most abundant. Two routes of arrival within the modern range of Ivory-billeds seem possible: through n. Mexico and around the Gulf Coast to the southeastern states and then to Cuba, or from the Yucatán Peninsula to Cuba, and then to the south-eastern states. Good evidence supports the notion that ancestral Ivory-billed Woodpeckers may have come through Mexico and across the Gulf Coast region of Texas to the se. U.S. and then from Florida to Cuba. During Pleistocene ice ages, sw. U.S. was much wetter and supported forests where today we find desert. Brodkorb (1970, 1971) described a fossil Ivory-billed relative, Campephilus dalquesti, from Scurry Co., northwest of Abilene in w. Texas, where it lived during the Upper Pliocene perhaps 4 million yr ago. Lowered sea levels during the peak of Pleistocene glaciation meant that peninsular Florida extended much closer to Cuba, thus facilitating dispersal of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers across the Flor-ida Straits (Jackson 1991b). Lowered sea levels during Pleistocene glaciation would also have brought the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico closer to Cuba, facilitating movement of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers from Mexico to Cuba to Florida. This is a puzzle that may never truly be an-swered, but one worthy of further investigation. There is a third possibility. Early explorers noted a considerable trade in live birds between peoples of Cuba and peninsular Florida (Jackson in press). Perhaps Ivory-billeds were introduced to Cuba sometime before the arrival of Columbus in the New World. Native Americans placed great value on these woodpeckers. If any were taken captive and kept alive, their powerful bills would certainly have facilitated escape. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/DISTRIBUTION.html#Ivory-billed_Woodpecker_DISTRIBUTION_OUTSIDE_THE_AMERICAStinyurl.com/7qclfCSUBSPECIES Two subspecies recognized (Peters 1948, Am. Ornithol. Union 1957). Although formerly treated as separate species, these appear to be weakly differentiated, allopatric subspecies (Mayr and Short 1970). C. p. principalis (Linnaeus, 1758); type locality restricted to S. Carolina. Entire range of species in se. U.S. C. p. bairdii (Cassin, 1863); type locality Cuba. Range restricted to island of Cuba. Characters given to diagnose this race by Ridgway (1914) included smaller size (wing 236–255 mm and culmen 58–61 mm vs. wing 240–263 mm and culmen 61–72.5), white stripe on side of head extending anteriorly nearly to rictus, and nasal tufts smaller. In his original description of C. p. bairdii, Cassin (1863) described birds from Cuba as being much like U.S. birds, but smaller, having black feathers at front of crest longer than scarlet feathers just behind them, and in having white line of neck extending almost to bill. In C. p. principalis, scarlet feathers of crest said to be longer than black feathers just in front of them, and the white line extending up each side of neck to end farther back from bill (usually beneath middle of eye). While Cuban Ivory-billed averages smaller than U.S. specimens in bill dimensions, it overlaps Florida specimens greatly in wing, tail, and tarsal measurements (Short 1982) and there is considerable variation among and overlap between Cuban and Florida specimens in plumage characteristics (Cory 1886, Short 1982); see also Appendix. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/SYSTEMATICS.html |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 17:55:07 GMT

Habitat

CUBA

CUBA

Because of the extent of cutting and degradation, Lamb (1957) considered it impossible to know much about what Ivory-billed habitat had been in Cuba. Like its U.S. counterpart, the Cuban Ivory-billed was a bird of vast, old-growth forests with large trees, a steady supply of recently dead trees, and probably an open canopy (Lamb 1957, Short 1982, Short and Horne 1986, García 1987, JAJ). Early records suggest a similarity in habitats of U.S. and Cuban Ivory-billeds, but by the last half of the nineteenth century, the Ivory-billed in Cuba was restricted to uplands; quick-draining lateritic soils provide the conditions for development of the extensive pine uplands the species then favored (Lamb 1957). Lamb found the birds nesting in pines and occasionally foraging in hardwoods. In de-scribing the vastness of the area required, García (1987) noted that the home range of a pair of Ivory-billeds could support 30 pairs of West Indian Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes superciliaris).

FEEDING

Main foods taken

In both the U.S. and Cuba, beetle larvae of the families Cerambycidae, Bup-restidae, and Elateridae (Allen 1939; Tanner 1941, 1942a).

Microhabitat for foraging

In Cuba, Lamb (1957) found Ivory-billed Woodpeckers divided their foraging efforts about equally between pines and hardwoods.

Food capture and consumption

In both the U.S. and Cuba, primary foraging method was to strip bark from recently dead trees by using its bill much like a carpenter’s wood chisel to reveal beetle larvae ( Fig. 2); also sought wood-boring insects in small trees and fallen logs, splintering them in its search for food (Allen 1939). Less often would excavate in a manner similar to Pileated Woodpeckers—dig-ging deeper, slightly conical holes into rotted wood in search of larvae (Tanner 1942a, Lamb 1957). In a letter to Jim Tanner (4 Sep 1939), Herb Stoddard, who knew Ivory-billeds in his youth, described what he believed was Ivory-billed work on pines that had been killed by a hurricane in n. Florida: “The larger portion of the bark of these pines had been removed while it was still quite tightly at-tached, the evidence being left on the tree being comparable to that a man might leave who knocked off the bark with a cross hatching motion with a heavy screwdriver.”

This description fits the work Tanner described on hardwood trees in the Singer Tract and that I saw on pines in the mountains of e. Cuba in 1987 and 1988. Dennis (1984) contrasted the structure of Ivory-billed and Pileated bills and their foraging methods, suggesting that the former was specialized to take advantage of larger larvae in recently dead large trees that were inaccessible to the less chisel-like bill of the Pileated, but that the Pileated was more of a generalist and as a result did well in a diversity of habitats while the Ivory-billed disappeared as the virgin forests (larger trees) disappeared.

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 18:04:58 GMT

MOLTS AND PLUMAGES Definitive Basic plumage Male. Overall color glossy blue-black, glossed with green below (Baird et al. 1858), rectrices and remiges less glossy. Nasal tufts overlaying bill white. Head with prominent crest. Front edge of crest black (extending almost to tip of crest); remainder of crest scarlet red. Red feathers longer than black feathers in most U.S. birds, but black feathers longer than red feathers in many Cuban birds. Basal third of red feathers also white, such that when feathers are erected, bird might display a white spot (JAJ). No author has mentioned this, but it is clearly illustrated by Wilson (1811). A white stripe beginning somewhat below eye (or slightly anterior to eye in some Florida and many Cuban specimens) extends back to neck, down side of neck, and then through outer rows of scapulars. White stripe ends on distal outer scapulars, where it meets inner edge of large white patch present on folded tertials and secondaries (see below). All secondaries and tertials white, and P1–P5 show extensive white distally; P6 rarely shows white distally (Ridgway 1910). Together these white feathers form a prominent white patch on wing. Tips of loosely webbed feathers that surround cloaca often white, though these not conspicuous. Undersurface of wing black except secondaries and distal portions of inner primaries white, and all under wing-coverts white (Baird et al. 1858). Together these areas form 2 large white patches on leading and trail-ing portions of open under-wing surface; rectrices pointed. Tail graduated. Many specimens also have irregular white markings near tip in outer web of outermost rectrix, R5. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/APPEARANCE.htmlMEASUREMENTS LINEAR | MASS LINEAR Largest woodpecker known to have lived in North America north of Mexico. Appendix provides standard anatomical measurements from specimens ex-amined from numerous collections. Based on measurements taken, males from the 2 largest samples (n. Florida/Georgia and s. Florida) averaged only slightly larger than females in wing-chord, and length of culmen from distal edge of nostril. This pattern also apparent for most other samples. Sample from Texas and Louisiana differed as a result of overall smaller measurements for a single male specimen taken in Jul (possibly a juvenile misidentified as an adult). Females exceeded males in tail length in 4 out of 7 samples, but many specimens had an exceedingly worn tail. A woodpecker tail wears greatly over the course of a year as a result of abrasion with tree surfaces, and inadequate numbers of Ivory-billed specimens are available to compare birds in fresh plumage. Cursory evaluation of data from various regional samples suggests the species varies geographically in size, larger to the north, smaller to the south, and smallest in Cuba. In addition to measurements in Appendix, however, are some measurements no longer possible to obtain—total length and wingspan measured on fresh specimens. In the course of examining Ivory-billed specimens, I noted 5 (2 adult males, 3 adult females) for which these measurements were given on the original specimen label. All 5 birds were from Florida, the largest male from n. Florida, the remainder from s. Florida. Total length of the 2 males averaged 50.2 cm (50.8, 49.5), and for 3 females 47.8 cm (45.7, 48.3, 49.5). Wingspan of 2 males averaged 79.2 cm (79.7, 78.7); for 2 females, 77.5 cm (78.7, 76.2). An extraordinary aberrant specimen of a female Ivory-billed was collected in Cuba by Juan Gundlach and described by Cory (1886). The bird had an overgrown upper bill such that it could not wear normally and hence grew out, curving downward to a length of about 43 cm (JAJ). In mid-nineteenth century, Gundlach (F. García pers. comm.) discovered the adult-plumaged bird along with an adult male and female Ivory-billed. He was curious as to how the aberrant bird fed, followed the trio for 3 d, observing that the aberrant bird could probe into arboreal termite nests to feed, but that it was also being fed by the other 2 adults. Then he collected all 3. The specimens are in the collections of the Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, in Havana, Cuba (adult male #2226, adult female #11, aberrant female #5999). bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/MEASUREMENTS.htmlPRIORITIES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH The priorities for future research with Ivory-billed Woodpeckers should include: (1) documenting any existing living birds and unobtrusively quantifying their interactions with the biotic and abiotic components of their ecosystem; (2) continuing efforts to identify and inventory existing specimens, including those associated with Native American artifacts; (3) maximizing efforts to link specimens with data; and (4) retrieving and archiving DNA for the species. Additional efforts should include use of molecular techniques to better understand relationships among Campephilus woodpeckers, especially between the Ivory-billed and Imperial woodpeckers, and between U.S. and Cuban populations of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/PRIORITIES_FOR_FUTURE_RESEARCH.htmlHistorical range of the IBW in Cuban and the USA  Introduction The Ivory-billed Woodpecker was once found in virgin forests throughout much of the southeastern United States and up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers at least as far north as St. Louis. It was also known from mature forests through much of Cuba. The past 100 years of this species’ history link U.S. birds to bottomland swamp forests and Cuban birds to upland pines. In truth, throughout its range, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker was associated with extensive old-growth forests, the solitude of wilderness, and the availability of immense beetle larvae that were its principal food. The specific forest types in which it survived may have been an accident of human actions. Human attention to this lord of the forest and human destruction of its realm have led to its cur-rent status as one of the rarest birds in the world, or extinct. In spite of a continued flow of unsubstantiated reports, some with tantalizing but inconclusive evidence, the scientific community has no conclusive documentation for recent occurrence of the species in the United States. The population in Cuba seems little better off, its habitat decimated and the last reported (undocumented by photos or sound recordings) sighting in 1992 (J. McNeeley pers. comm.). James Tanner (1942a) took the last universally accepted photos of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in the United States in northeast Louisiana in 1938; John Dennis (1948) took the last photos of this species in Cuba in April 1948. bna.birds.cornell.edu/BNA/demo/account/Ivory-billed_Woodpecker/INTRODUCTION.htmlthe last photo of a living bird in Cuba:  |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Oct 31, 2005 18:08:10 GMT

Thanks for the last photo melanie, I have never seen a living specimen of this suspecies before only stuffed once.

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Oct 31, 2005 18:23:01 GMT

Have You seen the photo on page 15 ?  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Oct 31, 2005 18:35:48 GMT

I think you mean the Gundlach photo on page 15 in the ivory-billed woodpecker book. Yes, the bill looks rather horrible. Have You seen the photo on page 15 ?  |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Oct 31, 2005 19:06:19 GMT

Yes, unbelievable.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Oct 21, 2006 15:36:37 GMT

CUBA 2003:

Searching for information on the Ivorybill

A Trip Back in Time

I spent time in Cuba in February 2003 to do some investigation on the possibility there are remaining Ivorybills in remote areas. If there are, a likely place to look would be eastern Cuba. This trip was more information gathering than anything else. Searching for the bird would require much longer than a week.

I flew to Holguin on Feb.15th 2003 and rented a car. I drove south to Bayamo and east to Santiago de Cuba where I stayed the night. The next day I continued past Guantanamo and into the mountains near Baracoa. This was relatively close to one of the largest national parks in Cuba - Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt. It stretches for miles in all directions into areas that are unexplored and almost unpopulated. Travelling around in Cuba was like going back in time to an old country western city. There are old 1950 Chevy and Ford cars from before the embargo and life is slow, relaxing and enjoyable. Horse-drawn wagons with wooden spokes are one of the main modes of transportation in most outlying cities. There are very few new cars and it's hard to find Coca Cola. Forget about fast food. Cowboys are seen everywhere on horseback there is no hint of modern technology anywhere. It was great to see that some parts of this world are still untouched. Cuba seems stuck in time - in the 1950s, perhaps. The scene was prophetic, given that I was searching for a bird seen only a few times since the 1950s.

The pine forests of eastern Cuba: where I had been thinking of going since my interest in the Ivorybill developed 15 years ago after I got my first National Geographic bird guide. In the book it describes Cuba as being one of last possible places to find it. Arriving at the park I was guided to a bird chart in a little hut at one of the entrances to this vast area. I was interested in talking with the man who would show me around, a man who might know something about the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. He showed me the birds on the chart. The Ivorybill stood out. I didn't recognize many of the other birds but the Ivorybill looked more flamboyant than anything else on that chart. I asked him what he knew. "El Carpintero Real es en peligro de extincion" he said. I knew right away that meant "The Ivorybill is in danger of extinction". Just to be in a park where the Ivorybill is shown on the bird chart is exciting to me, and to talk further with this man was incredible. Diogene was his name, and he knew the forest well. He was hired back in 1987 to help preserve the area and to teach people how to protect the wildlife. He continued to tell me how unexplored the area is. To hike to the top of the nearest mountain would take a whole day. That is what we did. However, to hike further in would take 4-5 days. It is steep and there are no trails. There is heavy undergrowth and the trees are enormous, the tops of which are lost in the canopy. He said the birds have not been seen since the late 1980s. In his opinion there is still a possibility that a few birds exist "en el nucleo" - in the center of the park, where only a few people have been. Those who have studied the Ivorybill are fully aware of the searches that took place in that very area in 1991 and 1993, coming up empty. Diogene still believes, as do I, that the area is vast enough and remote enough that the birds could have escaped detection. He said that it would take at least 4 days of hiking to get into some of the prime areas. I pictured the Tanner expeditions and the mule-drawn wagons - which almost certainly would have to be used in Cuba. The road itself to get to the park was almost impassable. It went from rugged pavement to gravel, then to dirt and then to mud. Finally, near the park entrance it was made of stones and boulders. The little car I had was not really sufficient. Basically this area is untouched and inaccessible, which is good for Ivorybills.

After gathering information I could sum it up as follows: The park workers are familiar with the birds (right up to the nest hole circumpherence!) and the type of habitat required. They seem to believe that the birds exist but that nobody has seen them. I believe anything is possible.

After leaving the Baracoa area I headed west towards the Sierra Maestra and the Santo Domingo area. They have a lodge with cabins and tour guides as well. The Sierra Maestra is an even larger, more daunting mountain range than what I had previously seen. The local bird expert again showed me his book with the Ivorybill pictured and the same type of bird chart that was at the Alejandro de Humboldt park. He also said that the bird has not been seen in years and that he had participated in 2 expeditions to find it with no luck, the most recent being in 1996. He also believes that a few birds may live in the Sierra Maestra although it's not clear if the Ivorybill was ever seen in this mountain range. I went on a one day hike of 11 miles to the top of one of the mountains. The habitat was ideal the further in we went. Some pines were 4 feet in diameter and close to 100 feet tall. According to this guide, Luis Angel, the trees were 100 years old. On the side of the mountain some of deciduous trees were equally as large. There were other woodpeckers in the area, including Cuban Red-bellied Woodpecker, which at 12 inches, was tough to see in the monstrous trees. Luis pointed to an area in the distance where he said there is an ongoing search for Ivorybills. I was not expecting to see the bird but nevertheless I was still hoping that at any moment one would fly in!

No Ivorybills were seen but for that short opportunity to be in the range of the bird and in the habitat was very exciting. It was mystical at some points, especially high on the mountain. It was very humid and clouds on a couple of occasions engulfed the forest. The strong sun became a faded pale yellow haze and the jungle-like atmosphere reminded me of something primeval - something I had never seen before. I felt as though this would be as close to the Ivorybill as I might ever get. The scene was perfect. I thought of organizing a proper search at some point, something as complex and cumbersome as the expeditions of the 1930s - because that would be the only way to succeed. This habitat is as difficult to explore as that in Louisiana.

I spent time visiting the local libraries in Holguin and Baracoa. Old field guides did exist and showed the former range of the Ivorybill. One bird expert in the Baracoa library was very familiar with the research that had been done recently. She also believed that as many as a few pairs could exist in either mountain range in eastern Cuba. She said more research is needed.

Overall, people seem to believe the bird could still exist. Hope for some is still there. Whether it be in Cuba or in the US, the persuit for Ivorybills continues to this day in the most serious manner.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Oct 21, 2006 15:39:41 GMT

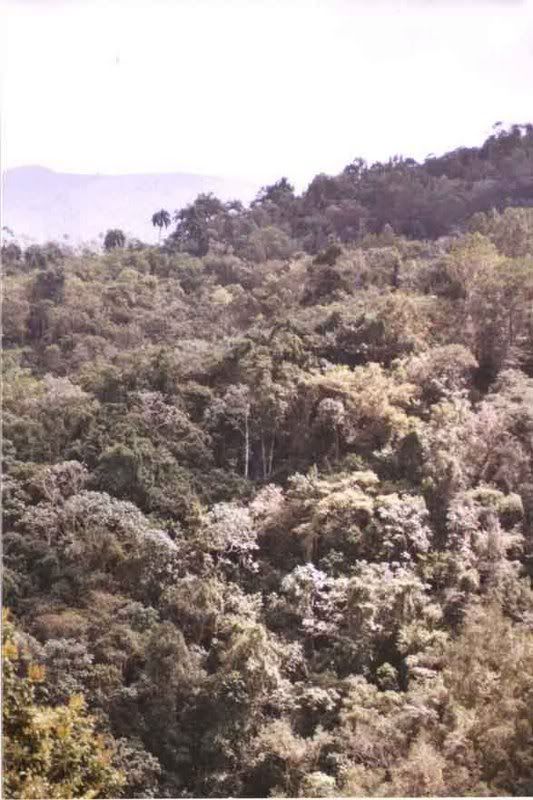

Near Baracoa. In the distance is where the last known Ivory-billed Woodpecker was seen. Over that mountain ridge is uninhabited and unexplored territory that extends for miles. Only a few groups have searched the area since the late 1980s. What is actually in there remains a mystery,  The guide helped me navigate through thick, heavy underbrush and following the streams seemed to be the easiest way. Unlike the forests of Louisiana the foliage remains on the trees throughout the year making it much more difficult to view birds. This is the range and habitat of the Ivorybill. Perhaps one day someone will see the bird. For now, if there are any left they go about their daily lives without ever seeing a human.  This picture gives an idea of the habitat around Santo Domingo. This mountain range extends for miles and is not well explored. The guide said that a recent search for Ivorybills came up empty but that he still has hope that they could exist in unexplored sectors of the Sierra Maestra. He said the area is so vast that a year of exploration by any one group might still not be enough time to thoroughly cover the area. The trees here are towering and very old. www.geocities.com/miami13_dan/Ivorybill5.html |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Nov 26, 2006 11:34:06 GMT

Cuban ornithologists will seek the Peak with ivory nozzle in the forests of pines of the Maestra Sierra in the east of the island (to read our article on Cuba). This very wooded zone was prohibited access, including with the scientists, since Fidel Castro had reached the capacity almost 50 years ago. This new forwarding, financed by International Birdlife, began at the end of April. Arturo Kirkconnell, joint author of work “A Field Guides to the Birds Cuba off” and one of the best experts of the island, affirms: “I think that the bird is still here; we are likely now to prospect sectors ever visited before; the habitat is ideal, and there is no proof that the peak is not present any more in this zone.” The reason for which the cuban mode decided to open with scientific exploration some sectors isolated from the province of Guantanamo, in the east of the island, and of Pinar LED Rio, in the west of Havana, is not very clear, including for the scientists concerned. The foreigners experts of the project estimate that preceding prohibitions would be related to reasons of safety of the state and bureaucratic imagination. David Wege, the director of the Antilles program at International Birdlife, specifies that “the Maestra Sierra was variablement open during three or four last years, and coming from a closed administration, it is rather an incoherent thing”. The launching of a research of the Peak with ivory nozzle in Cuba follows the rediscovery (discussed, lira the Peak with ivory nozzle of Arkansas: an aberrant Peak?) species in Arkansas in the United States in April 2004. This event, announced officially in April 2005, involved a programme of protection of several thousands of hectares of easily flooded forest and a partner of international promotion. In Cuba, where people fight with the daily newspaper for their survival, a forwarding to find a rare bird has little chance to mobilize crowd. But to try to check the existence of the peak could constituted a positive element for the image of the nation on the level of the environmental protection. David Wege estimates “that there is an important chance so that the species survived in vast forests little known; and therefore of the money is put in this research”. Eduardo Inigo-Elias, an ornithologist of the University of Cornell, who directs research of the Peak to ivory nozzle in Arkansas, precise “which it remains in Cuba less mediums favorable for the peak than to the United States, but that the island has 600 protected sectors, and that this interest for the species is a good sign”. It adds: “I hope that one day one will be able to say that it was found!”. Formerly widespread in the old forests of the south-east of the United States and Cuba, the Peak with ivory nozzle is the second larger peak of the world after the imperial Peak. The last universally allowed photography of the bird was precisely taken in Cuba in 1948. Since then, the bird would have been seen several times in the United States and Cuba. The last reliable data on the island was obtained in the province of Guantanamo in 1986 by Lester Short, then president of American Museum off Natural History of New York. But Arturo Kirkconnell, 46 years, conservative of the National Museum of Natural History of Cuba, is certain to have heard the typical double tambourinage of the peak in 1999 in Pinar LED Rio. He also said to have collected reliable reports/ratios of observations on behalf of foresters in the Sierra of Maestra. www.ornithomedia.com/infos/breves/breves_art1_17.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 17, 2007 8:01:06 GMT

The Cuban Ivory Billed Woodpecker was thought to be extinct from the 1950s until 1986 when 2 individuals where observed in the Zapata Swamp. Unfortunately it was not seen again since then and so it is feared to extinct again. The American Ivory Billed Woodpecker was thought to be extinct since 1944 until 2004 when 2 scientists saw an unclear silhouette of a large woodpecker in Arkansas. The rediscovery was confirmed after they have checked the recorded sound protocols. They confirm with a high certainty the the existence of the IBW in Arkansas. There is a new survey in Arkansas since November 2005 and the hope is big that the IBW has still survived. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 17, 2007 8:03:56 GMT

Renamed thread and merge both extinct threads.

This thread is only for the Cuban subspecies not the usa subspecies.

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Mar 8, 2007 21:16:47 GMT

Newly Found Ivory-bill Images Four previously unpublished photographs of Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpeckers By Tim Gallagher So few photographs of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker exist that it is always exciting when previously unpublished images of the bird show up. We are pleased to present some newly found images here—all of them depicting Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. The picture above was taken by ivory-bill researcher George R. Lamb during his 1956 research expedition to Cuba. A recent college graduate, Lamb and his wife, Nancy, spent several months searching for and eventually studying a small remnant population of ivory-bills in northeastern Cuba, near Moa. The International Committee for Bird Preservation had given them a joint fellowship for studying rare Caribbean bird species, and the ivory-bill was a perfect candidate. The two spent weeks camping out before finding any ivory-bills. They had a number of sightings and found a roost hole, but ultimately did not locate any nests. Although Lamb published a paper about their Cuba research the following year (Lamb, G. R. 1957. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Cuba. Pan-American Section, Int. Comm. Bird Preserv., Res. Rep. no. 1), he did not include any photographs of the birds they saw. I tried in vain to locate George Lamb while I was writing my book, The Grail Bird. I was eager to interview him about his experiences in Cuba. Unfortunately, I didn’t find him until my book was already published, but I did subsequently have some interesting conversations with George and Nancy Lamb. During one of our talks, he happened to mention that one day during his research expedition to Cuba he had taken some Ektachrome slides of a female ivory-bill foraging on a pine tree. He told me they were not great pictures. His camera did not have a telephoto lens, so the bird’s image was fairly small. Obviously, I was very interested anyway, and he said he would try to find them for me. Several months later, he found six images and sent the best one to me. I was excited to see that, although the bird was tiny in the photograph, it was clearly identifiable as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, so we are publishing it here—along with a blown-up detail of the bird from the picture. Photo courtesy of Harold Bucher I also recently found out about some other intriguing Ivory-billed Woodpecker pictures. Alan W. Knothe, a birding guide for Nature Tours who lives in the Florida panhandle, told me that Harold Bucher, an elderly Florida man who had lived in Cuba as a child, had some old black-and-white pictures of ivory-bills taken by his father shortly before World War II. Bucher’s father and a partner had opened a sawmill near Moa in northeastern Cuba during the late 1930s, when the area was still quite wild and remote. A couple of years ago, Bucher was cleaning up after Hurricane Charley when he discovered the pictures in his father’s personal effects. One of them (left) depicts an ivory-bill perched on the trunk of a dead tree, right beside a large cavity—perhaps the bird is at its nest or roost hole. The other two pictures are disturbing, depicting two different views of a captive Ivory-billed Woodpecker perched on a stake, with a length of twine tied to its leg (below). We are publishing these pictures here for the first time. Unfortunately, no data were attached to these photographs, except for the year “1941” scrawled in ink on the back. Bucher is fairly certain that the pictures were taken near Moa, but we have no way of knowing exactly where or what happened to the birds in the photographs, so they may remain a mystery. Photos courtesy of Harold Bucher We are always eager to receive Ivory-billed Woodpecker reports (or pictures), even old ones like these. They all help to fill in the pieces of the puzzle about the ivory-bill. So few pictures and first-hand observations exist for this species, that everything we get is vital. To find out the latest information about the ongoing searches for this species, visit the "Current Search" section of this web site. And to report a sighting (or to tell us about a photograph) send an email to ivorybill@cornell.edu. This is the web version of an article that first appeared in the Winter 2007 edition of Living Bird.     source: www.birds.cornell.edu/ivory/latest/cubaIBWOphotos/document_view |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 28, 2007 21:26:24 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Nov 29, 2007 12:51:43 GMT

Part on Cuban ivory-bill copied from a text in the North American Ivory-Billed thread: extinctanimals.proboards22.com/index.cgi?action=display&board=otherextinctbirds&thread=1170793550&page=5. The Cuban ivory-bill: Baird’s bird?Will field guides soon list two species of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers? Although the authors of the new study suggest that Cuban and North American ivory-bills should be considered separate species in their own right, the official decision rests with the American Ornithologists’ Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature. Lovette, a member of the committee, said decisions to split or lump species are usually based on multiple lines of evidence. “The new data are intriguing, but place these birds in the gray zone where some biologists would classify them as two species and others would retain them as just one,” he said. “These results will likely initiate an interesting debate on how we should classify these birds.” If, at some point, the Cuban bird becomes officially recognized as its own species, the story of the woodpeckers’ shifting taxonomy will have come full circle. The Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpecker was named for an early Smithsonian Secretary, Spencer Baird: Campephilus principalis bairdii, in the subspecies nomenclature. But based on the work spearheaded by the Smithsonian, the species list might eventually read Campephilus bairdii, or Baird’s Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Until then, ornithologists will once again be involved in debate over the enduring enigma that is the ivory-bill. Wandering WoodpeckersTheories about how Ivory-billed Woodpeckers made it to Cuba have included the possibility that Native Americans transported the North American ivory-bill to that island as recently as 600 years ago. By showing that the Cuban population is genetically distinctive, the new study provides solid evidence that the woodpeckers were on the island long before people ever got there. Martjan Lammertink, a researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, said the genetic data suggest a likely natural pathway of colonization: “From Central America, one group crossed during a low-water period from Yucatan (Mexico) to Cuba. Another group went to the Sierra Madre and became the Imperial Woodpecker, and the rest went farther north and became the North American Ivory-billed Woodpecker.” Because conditions were harsher in the mountains, researchers hypothesize that the Imperial Woodpecker became bigger and heavier than the other two to withstand the cold. The original paper and supporting material is provided below courtesy of The Royal Society.

Mid-Pleistocene divergence of Cuban and North American ivory-billed woodpeckers

Biology Letters, May 16, 2006, DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0490

Robert C. Fleischer, Jeremy J. Kirchman, John P. Dumbacher, Louis Bevier, Carla Dove, Nancy C. Rotzel, Scott V. Edwards, Martjan Lammertink, Kathleen J. Miglia, and William S. Moore.

Supplemental Material--------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Source: www.birds.cornell.edu/ivory/latest/woodpeckerDNA/document_view |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 29, 2007 20:41:45 GMT

Part on Cuban ivory-bill copied from a text in the Divergence of ivory-billed woodpecker subspecies thread: extinctanimals.proboards22.com/index.cgi?board=articles&action=display&thread=1195404576&page=1Mid-Pleistocene divergence of Cuban and North American ivory-billed Woodpeckers We used ancient DNA analysis of seven museum specimens of the endangered North American ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) and three specimens of the species from Cuba to document their degree of differentiation and their relationships to other Campephilus woodpeckers. Analysis of these mtDNA sequences reveals that the Cuban and North American ivory bills, along with the imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) of Mexico, are a monophyletic group and are roughly equidistant genetically, suggesting each lineage may be a separate species. Application of both internal and external rate calibrations indicates that the three lineages split more than onemillion years ago, in the Mid-Pleistocene. We thus can exclude the hypothesis that Native Americans introduced North American ivorybilled woodpeckers to Cuba. Our sequences of all three woodpeckers also provide an important DNA barcoding resource for identification of non-invasive samples or remains of these critically endangered and charismatic woodpeckers. Download full-text pdf: www.oeb.harvard.edu/faculty/edwards/research/documents/BiologyLetters_Ivory-billed.pdf. Supplemental Material: www.birds.cornell.edu/ivory/latest/SOM.pdf |

|

kk1

Full Member

Posts: 63

|

Post by kk1 on Dec 1, 2007 12:01:35 GMT

I remember when the birds were sighted in 86-87 and I swear there was a National Geographic article with pictures, if someone has access to old issues please look it up.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 6, 2008 5:39:29 GMT

Hello,During the first week of March I visted Cuba.While in the town of Holguin visited the Museo de la Historia Natural Carlos de la Torre.I noted a pair of Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in a glass case with other woodpeckers. There was no information on the date obtained,region or such on the specimens.The specimens in the museum look they are great need of restoration. I hope to go back to Cuba first week of March and if so will check other musuems and send any photos I get off extinct birds of Cuba.If you go to my Webpage at : www.flickr. com/photos/ lostoros/ sets/72157604114 478054/ you will see photos I took of the specimen pair,forgive my photography as I was just using a small digital camera shooting through the glass case. Regards, Jim Forrest |

|