|

|

Post by cuxlander on Sept 25, 2004 17:12:22 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Sept 26, 2004 7:24:35 GMT

Definatelly the best website on the Steller Seacow (Hydrodamalis gigas) I have seen! A great source of information!

You will see my there more often!

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 28, 2005 5:05:50 GMT

a great website - keep up the good work

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 28, 2005 8:56:42 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 10, 2005 20:49:16 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 23, 2005 6:26:47 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Prolagus on Jul 26, 2005 21:48:16 GMT

I know that giant seacows lived on the coasts of Japanes and California about 1000 or 2000 Years ago, but was this the same species as the Stellers Seacow?

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 27, 2005 8:13:27 GMT

I know that giant seacows lived on the coasts of Japanes and California about 1000 or 2000 Years ago, but was this the same species as the Stellers Seacow? Different species not the same properly a manatee or dugong subspecies? |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 6, 2005 8:01:04 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Bucardo on Oct 23, 2005 0:59:31 GMT

I know that giant seacows lived on the coasts of Japanes and California about 1000 or 2000 Years ago, but was this the same species as the Stellers Seacow? I've heard that there have been found Steller' sea cow bones at California, but they are older, around 10000 years or more. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 23, 2005 9:06:49 GMT

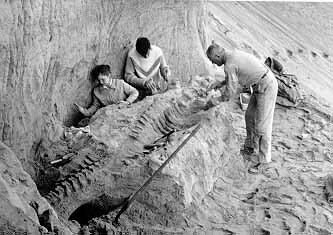

I know that giant seacows lived on the coasts of Japanes and California about 1000 or 2000 Years ago, but was this the same species as the Stellers Seacow? I've heard that there have been found Steller' sea cow bones at California, but they are older, around 10000 years or more. The fossil finds your mentioning belong to another species a descedant of stellers sea cow a relative in other words.... The Fossil Sea Cow by Frank Perry [In this photograph, Frank Perry is mounting the replica of the sea cow skeleton, which is exhibited at the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History]  The skeleton is from a fossil sea cow (Dusisiren jordani) that lived in the Santa Cruz area 10 to 12 million years ago. The specimen is a cast made out of plastic. It is an exact replica of the original fossil bones, which are at the University of California, Berkeley. The original bones would be too heavy and fragile to mount in this way. This species was previously called Metaxytherium jordani , the name used in my book. Sea Cows Sea cows are herbivorous aquatic mammals. Like cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) sea cows lack hind limbs and are thus restricted to life in the water. There are four living species: the West Indian Manatee, the Amazonian Manatee, the West African Manatee, and the Dugong, which inhabits the Indo-Pacific. A fifth species, the Steller's or Great Northern Sea Cow lived in the Bering Sea until hunted to extinction in the 1700's. Our fossil sea cow is an extinct genus more closely related to the Dugong than the Manatee. It was probably a direct evolutionary ancestor of the Steller's Sea Cow. Sea cows belong to their own separate order of mammals, the Sirenia. Within this order are two families: the manatees and the dugongs. Sirenians descended from land mammals and first took to the sea in the Eocene (38-55 million years ago). Note the vestigial pelvic bones, evidence of a distant terrestrial ancestor. The Fossil The bones were discovered in a Zayante sand quarry and collected under the direction of Dr. Samuel P. Welles of U.C. Berkeley in October, 1963. The animal rested on its back, with the bones laid out much as in life. The creature must have been buried soon after it died before currents and animals scattered the bones. It was a very old adult. Sea cows are not sexually dimorphic, so we can't tell if it was a male or a female. Note that several bones broke and imperfectly healed while the animal was alive. These include the left eleventh rib, right twelfth rib, the sternum (breast bone) and rostrum (front part of skull). The injuries seem to have been the result of a blow from underneath. Perhaps it was dashed against the rocks by a wave.  Ecology Dusisiren was common in the shallow coastal waters of late Miocene California. The climate was slightly warmer than today, and there were many more bays and inland seas over California. The sea cow fed on algae and sea grasses, pulling up the vegetation with the horny pads in the front of its mouth. It did not have front teeth. The Cast A two-piece rubber mold (more for the skull) was painted over each bone. After the rubber cured, the original bone was removed from the mold and plastic poured in to make the cast. The casts were then painted to look like the fossils. This cast was made by technicians at the Takikawa Museum in Japan. There are only two skeletons of this species on display in the world. Both are casts: one in Japan and the one here. Our specimen is on loan from the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley. Copyright 1995 Frank Perry. This article is printed by permission of Frank Perry. Photographs courtesy of Frank Perry Museum Services. www.santacruzpl.org/history/spanish/seacow.shtml |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Oct 25, 2005 12:20:19 GMT

I know that giant seacows lived on the coasts of Japanes and California about 1000 or 2000 Years ago, but was this the same species as the Stellers Seacow? It is true that one lived there, but became extinct way earlier as far as I know: the Dugong Seacow (Hydrodamalis cuestae). Similar to Stellar's sea cow, H. cuestae may have reached a maximum body length of about 9 meters (30 feet) and probably weighed close to 10 metric tons. The sirenians spread throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the early Eocene Epoch, from Japan to Baja California. Their populations peaked during the Miocene Epoch. www.sdnhm.org/fieldguide/fossils/dugong.html |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Oct 25, 2005 12:28:32 GMT

The range of Hydrodamalis gigas in historic times appears to have been limited to the coastal waters of the Komandorskiye and Blizhnie Islands in the Bering Sea. Accounts of sightings from other islands in the Bering Sea, along the northwest coast of North America and the northeast coast of Asia, in the Arctic Ocean and Greenland are difficult or impossible to confirm and generally discounted. Fossil evidence indicates that the past distribution of genus Hydrodamalis was much wider, including the coasts of Japan and North America. Fossil remains of Hydrodamalis cuestae are known from as far south as the southern coast of California. Source: Weinstein, B. and J. Patton. 2000. "Hydrodamalis gigas" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed October 25, 2005 at animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Hydrodamalis_gigas.html. |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Oct 25, 2005 12:31:24 GMT

In his writings, Steller described the giant sea cow and its habits, but was vague in his accounts of abundance and distribution. He said he found it numerous and in herds, leaving future researchers to guess at exactly how many. Stejneger (1887) estimated the number at less than 1500 and hypothesized that they were the last survivors of a once more numerous and widely distributed species which had been spared because man had not yet reached their last resort. Modern scientists agree that Steller's sea cow, and it's ancestors, H. cuestae, Dusisiren dewana, and D. jordani, were once widely distributed around the Pacific rim from Baja to Japan, where Hydrodamalis thrived until the coming of humans in the Pleistocene (Domning 1987). The ancestor to Steller's Sea Cow was possibly an extinct Dugongidae sea cow, Dusisiren jordani, previously named Metaxytherium jordani. Dusisiren was common in the shallow coastal waters of late Miocene California 10-12 million years ago. Although Sirenian evolution is not fully understood, there is a very clear and compelling fossil record leading up to Steller's sea cow (Domning 1987). Source: www.sirenian.org/stellers.html. |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Oct 25, 2005 12:38:52 GMT

Another relative from Japan: Furusawa, H. 1988. A new species of hydrodamaline Sirenia from Hokkaido, Japan. Takikawa (Japan), Takikawa Museum of Art & Nat. Hist.: 1-73. ["Hydrodamalis spissus", Early Pliocene. NOTE: Because the name Hydrodamalis is feminine, the specific name should be emended to spissa whenever it is used.] Source: www.sirenian.org/sirenews/12OCT1989.html. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 25, 2005 20:19:38 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Nov 6, 2005 17:21:42 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Nov 6, 2005 17:34:01 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 6, 2005 17:39:52 GMT

Gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Nov 6, 2005 18:25:53 GMT

|

|