|

|

Post by Peter on Apr 22, 2006 15:59:40 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 22, 2006 19:21:17 GMT

Thanks for inform us - just going to have a read. |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Apr 24, 2006 10:16:08 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 25, 2006 20:52:55 GMT

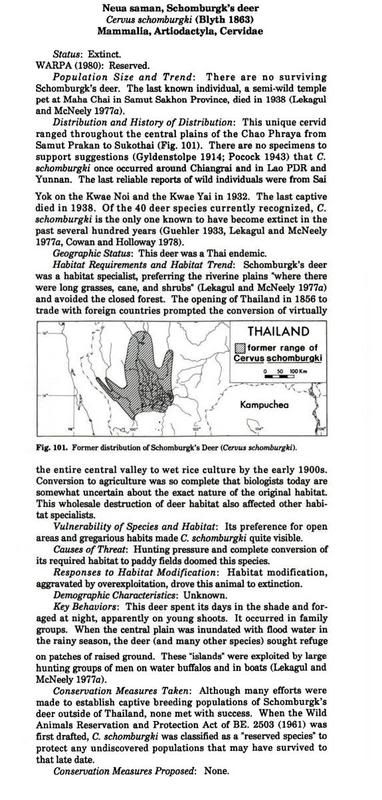

Schomburgk's Deer Species: Cervus schomburgki (Blyth, 1863) Synonym: Rucervus schomburgki (Blyth, 1863) Order: Artiodactyla Family: Cervidae Common names: Schomburgk's Deer; Sman (in Thailand) The sman is unique to Thailand and once roamed the central plains. It has a graceful body with beautiful antlers making it one of the most beautiful deer. But they were hunted into extinction in 1938. Today we are left only with pictures and stories from the past. It had two equal sized toes on their hooves and antlers were found only on the male. The brow tine grew to an angle of 60 degrees to the face and the length of each branch was about 30 centimeters. At each end were 2 sub-branches. The beam was about 12 centimeters in length and perpendicular to the brow tine. The branches grow on top of each other for two to three layers. On average each side had about 8-9 branches. This gave the sman's antlers an appearance similar to a basket thus earning it the name "basket deer". The average length of the sman's antlers was 65 centimeters. It measured at the shoulder a height of 1 meter. The body hairs during winter were rough and long and the color was brown with a darker shade or black found on the nose area. The cheeks, body, and underside of the tail were lighter. The female was very similar to the la-mang and caused villagers to believe that there was only male sman. They would mate with the la-mang and the offspring would be either a sman or la-mang. Living along the Chao Phya River plains around Bangkok and the surrounding areas, they roamed the area from Samut Prakarn to Sukhothai and in the east they were found in Nakhon Nayok to Chachengsao. On the west they were found from Suphan Buri to Kanchanaburi, truly native to Thailand. It did not like dense forests because their antlers would get caught in and lived in small herds feeding in the early evenings to the morning. During the day the sman would sleep and hide in tall grass. It is believed that the sman are now extinct from Thailand and from the world. The last reported sman has been shot in Kanchanaburi in 1932 and there was another report of one beaten to death at a temple in Samut Sakorn in 1938 because it came too close people. There has been no reports of sightings of the sman from that day to the present. Prior to the extinction there were efforts by foreigners to capture these animals and breed them, however all failed because the Thais did not cooperate because they do not see the importance. www.tscwa.org/wildlife/rare_or_extinct_07.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 25, 2006 20:55:13 GMT

Shomburgk's Deer Cervus schomburgki, named after Sir Robert Schomburgk and endemic to only Thailand, were once very common in the lush swamps along the Chao Phraya River and on several of the great swampy, grassy plains around Chiang Rai and Sukothai. However, due to the increased cultivation of rice, human encroachment and hunting it is believed that the species is now extinct. The shoulder height was about 1m with a dark shiny brown body and short tail with a light ventral surface. Congregating in small herds in the mating season, at other times the bucks tended to stay on their own. The buck had an antler that was quite distinctive, with a very short beam and 10-33 tines arranged in a basket like fashion. www.cpamedia.com/research/schomburgk_people/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 25, 2006 20:56:30 GMT

Schomburgk's Account of 'The Lao' in 1859-60 Part of Ancient Chiang Mai Sir Robert Schomburgk, the British Consul to Siam who visited Chiang Mai (which he styles 'Xiengmai') in 1859-60, left a somewhat convoluted account both of the city and of its people, who he styles 'Lao' following the convention of the time, though by this he means very specifically the Khon Muang. Of Chiang Mai and its people he writes: We found a large number of people assembled between the bridge and the city gate to witness our arrival; some were standing; others, sitting in groups or pressing near us. They were a medley crowd. The true Lao in turbaned kerchief, with his tartan-like Khatung, worn as the Scotch wear their plaid; the Thai or Siamese merely girdled round the loins; the fat smiling Chinese in his blue vestments; and to make the medley still more conspicuous, there were likewise inhabitants from Muang Teli [Dali] in the Chinese Province of Yunnan, a caravan of which had arrived a day or two previous: all these people added to the peculiarity of the scene before us. Fatigued, I slept soundly, but what a stir there was on awakening, from the early morning hours, in front of our residence. The bridge is the great public thorough-fare for the population residing on the left bank of the Méping, not only in the suburb, but likewise for those in the adjacent country. A number of these persons come daily to town, to sell or purchase: the women entered in parties, consisting of twenty or thirty; seldom accompanied by men, passing in single file towards the city gate. The Lao females, have long glossy hair of an intense black, which, with tidy persons, is neatly plaited and gathered in a knot behind, the hair of the forehead being drawn up backwards in the manner of the Chinese women. They wear the Lao petticoat, more or less ornamented with gold thread, and embroidered with silk of bright colours. The married women are moreover dressed in a jacket or spenser, closely fitting as far as the waist, and from thence expanding more amply until it reaches nearly to the knee... Those who can afford it, have rich necklaces, and rings in their ears and on their fingers; their arms and ankles surrounded by circlets of gold or silver; a silk shawl or scarf of red or rose colour is thrown loosely over their shoulders. The latter refers to the married women - young ladies, unmarried, do not dress above their waist. Black and shining as their hair is, the racemes of the white flowered Moringa [ton marum] or the fragrant Vateria , or if such be not in blossom, those of any other tree or plant similar in colour, set it off much more by the great contrast, when these flowers are placed in their raven tresses. The mouth of the young girls is formed exquisitely. But few of the Lao women indulge in betel chewing, hence they do not render that organ, so fairly formed by nature, hideous by the prevailing custom of the Thai; and their teeth remain white as nature made them. Though much fairer in colour, in stature they, like the Indians of Guiana, very seldom reach a height above 4 feet 10 inches.

The men generally wear the Khatung or Lao plaid, but a number are dressed in blue or white tunics, fitting closely and reaching like the spenser of the women to the knee. The hair of the head is allowed to grow; only when it becomes too long, it is cut; some have whiskers, a custom not adopted by the Thai, where nature has yielded him hairs on his cheeks. I observed but few instances of the tuft of hair on the crown, as worn by the Siamese proper.

They dress their children very neatly; on the head they place a cap consisting of seven pieces, in the shape of a cardinal's cap, made of scarlet cloth with a band of black velvet below, embroidered with gold thread. Boys of six years and upwards, are dressed in the close fitting tunic, and, according to the wealth and standing of the parents, they are made of velvet, or white cotton cloth...

The stalls in the bazaar are tenanted by women, who, when their attention is not claimed by purchasers, occupy themselves with making those pretty embellishments or embroideries worked with gold thread and all kinds of coloured silks, which adorn the Lao ladies' petticoats. Others were occupied in embroidering upon black velvet, ornamental designs according to their conception, for the covering of head cushions, and here and there the mother would have her... youngest to nurse, notwithstanding that her fingers were busily employed in embroidering. The silk for the manufacture of petticoats, &c., is imported from the Chinese territories.

The Laos consist, it may be said, of two clans, namely such as who, if men, paint their bodies from the waist to the knee, and designate themselves as the Thong dam or 'black bellies' and the others who do not paint, as Thong khao or 'white bellies'. I saw more of the former than of the latter in and about Xiengmai. The tattooing represents figures of dragons, tigers, labyrinths, &c. The operation of producing these figures is upon the same principle as our sailors employ, to have anchors, crosses and other figures printed upon their arms...

The customs of the Lao people resemble in general those of the Siamese. Marriage contracts are made verbally, the parents of the girl receiving a compensation from the future husband, for the loss which they suffer by having no further assistance from their daughter in their daily labour. The amount of that compensation depends upon the bride's beauty, youth and family connections. It seems the minimum is 40 Rupees (£4).

They practise cremation for such as die a natural death - that is, if the relations can pay the expense connected with it - but the remains of such as lose life by accident, as by drowning, by a fall, or being killed by an animal, cannot be burned but must be interred.

The smoking of cigars is very common amongst the women - they sometimes use pipes which are made of the rhizoma or rootstock of the bamboo, nicely carved. Little girls, no more than 6 or 7 years of age imitate their elders. It is quite amusing to see with what gravity these children enjoy their weed. On the other hand, I have not seen that the Lao females use the betel-nut to the same extent as the Siamese: hence, as I have already observed, they do not show those distorted mouths which disfigure the sex in Bangkok, and render their teeth black and corroded.

Text by Andrew Forbes, images by David Henley. © CPA Media, 2005

www.cpamedia.com/research/schomburgk_people/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 25, 2006 20:57:15 GMT

The above is just an interesting read so i uploaded it.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 8, 2007 21:06:26 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Sept 10, 2007 20:17:31 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 17:00:11 GMT

The Schomburgk's Deer (Cervus schomburgki) is a member of the family Cervidae. This deer was endemic to Thailand. The Schomburgk's deer was described by Edward Blyth in 1863 and named after Sir Robert H. Schomburgk who was the British consul in Bangkok from 1857-1864. The wild population of Schomburgk’s deer is thought to have died out around 1932, with the last captive individual being killed in 1938. The species is also listed as extinct in the 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1] However, some scientists consider this species to be still extant.[2] The Schomburgk's deer inhabited swampy plains with long grass, cane, and shrubs. This deer avoided dense vegetation. Commercial production of rice for export began in the late nineteenth century in Thailand leading to the loss of nearly all grassland and swamp areas this deer depended on. Intensive hunting pressure at the turn of the century restricted the species further until it became extinct.[3] In 1991, antlers were discovered in a Chinese medicine shop in Laos. Laurent Chazée, an agronomist with the United Nations, later identified the antlers from a photograph he took as coming from the Schomburgk's deer.[4] It is possible that the Schomburgk's deer survives in Laos, but further research is needed to confirm that. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 11, 2007 17:05:10 GMT

Synonyms Thaocervus schomburgki, Rucervus schomburgki Comments After the discovery of fresh antlers in 1991, the Schomburgk's deer may possibly survive in Laos. Until there is scientific proof of a living specimen The Extinction Website does not recognise its rediscovery and acknowledges that the species is extinct. Characteristics The Schomburgk's Deer had a graceful body with beautiful antlers making it one of the most beautiful deer. It had a body length of 180 cm (6 ft.), a shoulder height of 104 cm (3.4 ft.) and a tail length of 10,3 cm (4 in.). The Schomburgk's deer had a weight of 100-120 kg (220-264 lb.). Their upper parts had an uniform brown colour, with lighter underparts. The legs and area between the antlers had a reddish tinge. The short tail has a bright white ventral surface. The antlers have a length 32-83 cm along the outside curve and there are at least five tines on each antler. The females didn't have antlers. This deer had two equal sized toes on their hooves. (Nowak, 1999; Huffman, 2004) Lifestyle They lived in small herds consisting of a single adult male, a few females, and their young (Huffman, 2004). The Schomburgk's deer spent most of the day resting in shaded areas. The small herds were feeding in the early evening to the morning. Densely vegetated areas were avoided and most activity occurred on the open swampy plains. When flooding occurred during the rainy season, the Schomburgk's deer were forced to move to higher pieces of land, which often turned into 'islands'. Hunters, who would surround the temporary landmass and attempt to kill everything they could, frequently used these islands. (Nowak, 1999) Range & Habitat The Schomburgk's deer may once have occurred as far north as Yunnan (China) and Laos, but is known with certainty only from south-central Thailand. This deer occurred along the Chao Phya River plains around Bangkok and the surrounding areas, they roamed the area from Samut Prakarn to Sukhothai and in the east they were found in Nakhon Nayok to Chachengsao. In the west they were found from Suphan Buri to Kanchanaburi. In Thailand it inhabited swampy plains with long grass, cane, and shrubs. It avoided densely vegetated areas. (Nowak, 1999) Food This deer-species was a grazer, but did also eat fruits and leaves. Reproduction As far as I know there isn't anything known about their reproduction and life cycle. History & Population The Schomburgk's deer was described by Blyth in 1863 and named after Sir Robert H. Schomburgk who was the British consul in Bangkok from 1857-1864. Once they were abundant in Thailand. Commercial production of rice for export began in the late nineteenth century in Thailand and by the early 1900s it had led to the loss of nearly all grassland and swamp areas this deer depended on. Intensive hunting pressure at the turn of the century restricted the species further, especially when the herds were forced to crowd onto islands during the floods. By 1920 the Schomburgk's deer was virtually extinct, a few stragglers being reported on the Pu Kio range, where it was hunted by locals (Day, 1981). The last wild individuals are thought to have died around 1932. (Huffman, 2004; Nowak, 1999; World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 1996) The last known specimen of the Schomburgk's deer, an adult male, was kept as a pet at a temple in the Samut Sakhon province of Thailand. A drunk local killed this male in 1938 (Huffman, 2004). No confirmed reports of this species have since been heard and it is formally declared extinct in the 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, although rumours continue to suggest a remnant population may still survive. During a visit to a Chinese medicine shop in a relativley remote area of Laos in February 1991, Laurent Chazée, an agronomist with the United Nations, saw a pair of antlers for sale. Not recognising the species, he photographed the antlers. The shop owner told Chazée the antlers has come from a nearby district and that the animal had been killed in 1990. Later Chazée identified the antlers as coming from a Schomburgk's deer. (Schoering, 1995) Therefore it is possible that the Schomburgk's deer survives in Laos (MacPhee & Flemming, 1999). Further research is needed. Conservation Attempts The Schomburgks deer has been kept in captivity in some countries like Thailand, France (Paris) and Germany (Berlin, Hamburg). In 1870, the now disappeared Hamburg Zoological Garden (Germany) was the first zoo to breed the Schomburgk's deer (Reichenbach, 2002). Sadly, no Schomburgk's deer survived in captivity.. There is a forested region in area of Laos where the antlers discovered in 1991 purportedly originated. Local people consider this site to have strong animal spirits and hunting is prohibited there. This may explain why the Schomburgk's deer possibly survived in that area. (Schoering, 1995) Museum Specimens Paris Natural History Museum (Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle) in France. This specimen was brought back of Siam, current Thailand, in 1862, by Bocourt and lived in the menagerie of the Paris Natural History Museum where he died in 1868. It is the single mounted specimen in the entire world. Besides this mounted specimen only a few skulls and antlers survive. (Day, 1981) Relatives The Schomburgk's deer is thought to be closely related to the barasingha or swamp deer (Cervus duvauceli). (Schoering, 1995) Previously found throughout the drainage basins of the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers, the barasingha is today restricted to southern Nepal and northern India. Three subspecies are recognised: the wetland barasingha (Cervus duvaucelii duvaucelii) in India and Nepal, the upland barasingha (C. d. branderi) restricted to a single population in Madhya Pardesh, India; and the critically endangered C. d. ranjitsinhi found in only a single population in Assam, northeast India. (ARKive, 2006) Photo: Barasingha in Berlin Zoo, Germany. Photographed by F. Spangenberg (Der Irbis) in November 2005. The image is released under the GNU Free Documentation License. Links The Extinction Forum - Schomburgk's Deer Paris Natural History Museum (Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cervus schomburgki Schomburgk's deer - An Ultimate Ungulate Fact Sheet References ARKive. Barasingha (Cervus duvaucelii). Downloaded on 22 April 2006 from: www.arkive.org/species/GES/mammals/Cervus_duvaucelii. Huffman, B. 2004. Schomburgk's deer - An Ultimate Ungulate Fact Sheet. <www.ultimateungulate.com> Downloaded on 22 April 2006. Day, D., 1981, The Doomsday Book of Animals, Ebury Press, London. Deer Specialist Group 1996. Cervus duvaucelii. In: IUCN 2004. 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 22 April 2006. MacPhee, R.D.E. and Flemming, C. 1999. Requiem Æternam. The last five hundred years of mammalian species extinctions. In: R.D.E. MacPhee (ed.) Extinctions in Near Time, pp.333-371. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1936 pp. ISBN 0-801-85789-9 Reichenbach, H. 2002. Lost Menageries - Why and how zoos disappear (part 2). International Zoo News Vol. 49/4 (No. 317) June 2002. Available online at www.zoonews.ws/IZN/317/IZN-317.htm. Schoering, W.B., 1995. Swamp Deer resurfaces. Wildlife Conservation, vol 98, December, p22. Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (eds). 2005. Mammal Species of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2,142 pp. Available online at nmnhgoph.si.edu/msw. World Conservation Monitoring Centre 1996. Cervus schomburgki. In: IUCN 2004. 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 22 April 2006. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 27, 2008 10:11:33 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 15, 2008 12:14:37 GMT

Endangered Animals of Thailand By Stephen R. Humphrey, Humphrey, James R. Bain |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 13, 2008 18:39:40 GMT

Rucervus schomburgki Author: Blyth, 1863. Citation: Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond., 1863: 155. Common Name: Schomburgk's Deer Type Locality: "probably inhabiting Siam [Thailand]"; occurrence in central plains of Thailand since confirmed. Distribution: Thailand (extinct), China (Yunnan), and possibly in N Laos. Status: IUCN – Extinct (but see below). Comments: Included in duvaucelii by Haltenorth (1963:58) and Groves (1982b); but treated as a full species by Lekagul and McNeely (1977). Last Thailand specimen killed in 1932 (Harper, 1945); one record from Sanda Valley, Yunnan (Bentham, 1908; Sclater, 1891); present status in Yunnan unknown; recently observed antlers suggest another population may survive in N Laos (Schroering, 1995, and in litt.). www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?s=y&id=14200437 |

|

|

|

Post by Bhagatí on Jul 24, 2008 19:49:59 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Bhagatí on Jul 24, 2008 23:27:16 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 25, 2008 7:38:36 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 25, 2008 7:49:23 GMT

Thanks baghira for the pdf Would of been better if the images were clearer But anything is better than nothing. |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 9, 2008 8:11:48 GMT

Taxonomy [top] Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family ANIMALIA CHORDATA MAMMALIA CETARTIODACTYLA CERVIDAE Scientific Name: Rucervus schomburgki Species Authority Hodgson, 1838 Infra-specific Authority: (Blyth, 1863) Common Name/s: English – Schomburgk's Deer Synonym/s: Cervus schomburgki Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Extinct ver 3.1 Year Assessed: 2008 Assessor/s Duckworth, J.W., Robichaud, W.G. & Timmins, R.J. Evaluator/s: Black, P.A. & Gonzalez, S. (Deer Red List Authority) Justification: The wild Thai population of Schomburgk’s Deer died out around 1932, with the last captive individual being killed in 1938. None of the indications that the species inhabited other countries can be shown to have any compelling basis and some are clearly in error. Thus the species is considered a single-country endemic, to Thailand, where it is certainly extinct. History: 1996 – Extinct (Baillie and Groombridge 1996) 1994 – Extinct (Groombridge 1994) Geographic Range [top] Range Description: Rucervus schomburgki was endemic to Thailand and is thought to have become extinct when the last captive individual was killed in 1938; the last known wild animals were killed in 1932 near Sai Yoke and Kwae Yai, although this date was not universally accepted at the time (Harper 1945; Lekagul and McNeely 1988). The recent range in Thailand seems to have lain within 13°30′–18°N, 98°30′–102°E, comprising the central plain of Thailand (Giles 1937; Harper 1945; G.J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). Attempts to circumscribe the range have, however, been bedevilled by a surprisingly large number of statements of occurrence elsewhere. Statements of occurrence in the Sanda Valley, Yunnan, China by Sclater (1891: 180) and Bentham (1908) led to this locality being included without any caveat by Grubb (2005), and relate to both a frontlet and a skin. However, Sclater (1891) listed the set of antlers as of unknown locality, and the skin has a "?" mark that makes its Sanda Valley locality no more than tentative (G.J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). Then, Bentham (1908) indicated that the antlers had been collected in the Sanda Valley by John Anderson in 1878, without giving explicit source for this statement. In fact, Anderson was in the Sanda Valley in 1868, not 1878, and moreover recorded no such antlers in his thorough write-up of zoological results of his Yunnan expeditions. This locality assignment for the antlers should be seen as an error of Bentham's, presumably stemming from the earlier, tentative, assignment of Sanda Valley to the deer skin Sclater also reported (G. J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). Pocock (1943) included under distribution of the species “N. Siam [Thailand] and, it has been alleged, Yunnan and Lao PDR”, indicating his own concern with the Sanda valley ‘evidence’. The Shan states (Myanmar) have also figured as part of the species’s range, e.g. by Blanford (1891: 540). Reference to historical occurrence in these areas seems to stem from Brooke (1876), who wrote, based on written communication from a Dr Campbell of the Bangkok British Consulate) in reference to new specimens sent to him that ". . . all specimens were procured in northern Siam, probably even in the tributary states named Lao PDR and Shan". Campbell seems to have based his opinion at least partly on what professional indigenous hunters told him or others. Brooke gave no definition of "northern Siam" (conceivably it simply meant some way north of Bangkok), and Lao PDR in this context could well have included part or all of the Korat Plateau and other areas in present-day Thailand which are ethnically Lao and were often referred to in the past by terms such as ‘Siamese Lao PDR’. It is not even clear that Lao PDR and Shan were not just speculation on the part of Campbell and/or Brooke (G.J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). Not surprisingly, Harper (1945) considered the Shan states report to be “highly indefinite” and occurrence in “Indo-China” [presumably = Lao PDR, Cambodia and Viet Nam] to be “in error”, although he took the ‘Sanda valley’ frontlet as “apparently authentic”, perhaps being focussed on the identity (which is not in doubt) rather than the provenance (presumably assuming that the association with the highly-respected Anderson’s name was enough). A more modern reanalysis concluded that "the northern Thailand, Myanmar, Yunnan, and Lao PDR range extensions suggested in the literature are based on erroneous or quite inconclusive items of evidence", sometimes perhaps influenced by a switch of Thai names between Eld’s and Schomburgk’s deer by Flower (1900) (G.J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). Two loose antlers, presumed to be a pair, of Schomburgk’s deer photographed in Phongsali province, far northern Lao PDR, in 1991 were a most surprising find. This has been taken to suggest the species might survive, at least into the 1980s, and that it did indeed occur in Lao PDR (Schroering 1995) and it was even taken as sufficient evidence that the species was not extinct by MacPhee and Flemming (1999). However, while these are indeed Schomburgk’s deer antlers, it has proven impossible to recover a consistent story from their owner of the antlers’ origin (e.g. Duckworth et al. 1999) and there is no compelling evidence that they had come from a recently killed animal, rather than being decades-old stock still in trade; Williams (1941) noted that even then that Schomburgk’s deer antlers "keep coming down to Bangkok from Paknampo and Korat by railway amongst collections of ordinary deer-horns consigned to Bangkok Chinamen . . . the horns are probably quite old . . ." and Schomburgk’s deer antlers are still in trade in Thailand (Srikosmatara et al. 1992). The owner of the antlers was, according to his daughter, a middleman trader in wildlife parts sourced from all over Indochina (W.G. Robichaud pers. comm. 2008, based on visit in 1996). Consequently, while remains of the species have been seen in Lao PDR in recent times, they cannot be taken as evidence that the species survives today, or ever occurred in Lao PDR. Countries: Regionally extinct: Thailand Population [top] Population: Schomburgk’s deer was apparently “not uncommon” in the late nineteenth century and herds still occurred around 1900–1910 (Harper 1945), but the species underwent a very rapid decline: Harper (1945) stated that it was never seen in the wild state by a European (although this may be better taken as a lack of such reports, because Europeans working, for example, on the Paknampo railway in the early days would almost surely have seen and hunted these deer; G.J. Galbreath in litt. 2008). The usually successful hunter Arthur S. Vernay made three trips to Thailand specifically for the species, the first in 1920, but failed to see the species. There are some hundreds of skulls, frontlet and antlers in collections (Harper 1945), but the species is now extinct. Habitat and Ecology [top] Habitat and Ecology: The species inhabited seasonally inundated swampy plains with long grass, cane, and shrubs; it apparently avoided forest (Giles 1937), although there seems to be no information on where animals went at the height of the wet season, when much of the dry-season range was under water. Systems: Terrestrial; Freshwater Threats [top] Major Threat(s): Commercial production of rice for export began in the late nineteenth century in Thailand’s central plains, leading to the loss of nearly all the grassland and swamp areas that this deer depended on, and greatly fragmented what remained. Intensive hunting pressure at the turn of the 19th–20th century restricted the species further and it disappeared in the 1930s. Schomburgk’s deer was prominent in the antlers sought by the Chinese medicine trade (Harper 1945). During the wet season, animals marooned on higher ground were hunted readily with spears from boats (Harper 1945), no doubt hastening the species' decline. Conservation Actions [top] Conservation Actions: As an extinct species there are no appropriate conservation measures. The indication that a remnant population might still survive (Schroering 1995 and in litt. as reported in Grubb 2005; MacPhee and Flemming 1999) was followed up by investigation, independently by several people, of Phongsali province, Lao PDR, by field survey and interview. This failed to find any further evidence of the species there or to elicit a consistent story of the origin of the antlers (Duckworth et al. 1999; per J.W. Duckworth in litt. 2008). Given regional trends in Schomburgk’s deer’s sole known habitat, non-forest floodplains (its massive conversion to agriculture over the last 150 years) it is unlikely that the species could survive. However, any future indication of its existence should be followed up carefully. If by chance the species does survive, legislation giving it the highest levels of protection (in whatever country it was found), and an assessment of specific conservation needs would be imperative. www.iucnredlist.org/details/4288 |

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Aug 22, 2011 19:19:37 GMT

|

|