|

|

Post by another specialist on May 21, 2005 11:40:03 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on May 22, 2005 17:38:39 GMT

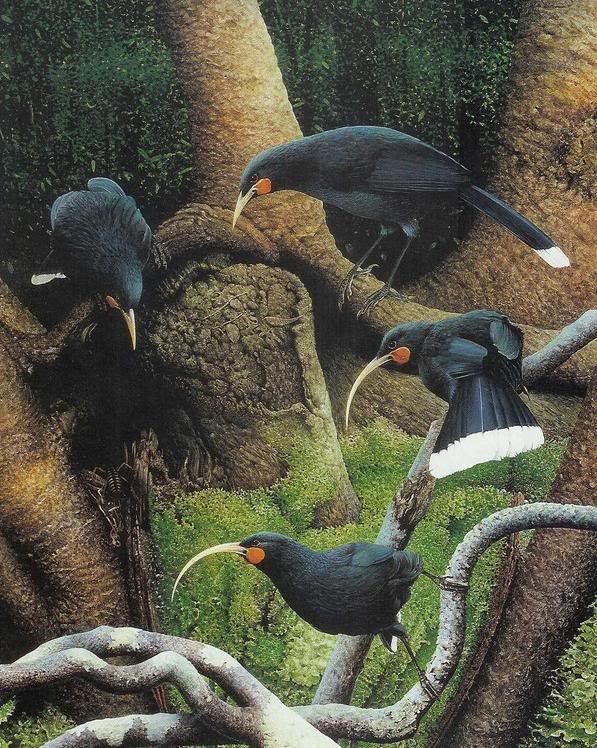

Huia Collected as a curiosity The Huia Heteralocha acutirostris ( Gould, 1836) was extensively hunted even before the first Europeans set foot in New Zealand. The bird was highly prized by the Maori for its tail feathers. Some believe that Huias were never common, restricted as they were to the southern part of North Island. It is therefore not surprising that, when hunting intensified with the arrival of the Europeans, the species declined rapidly.  Huia (male).  Huia (female). Different bills European collectors valued the bird for the peculiar difference between the sexes. The bill of the female is about twice as long as that of the male. The male used his short bill much in the manner of woodpeckers. The female delicately removed grubs and insects from the bark of trees before pinning them down with her claws and tearing them apart. For 19th-century collectors of the 'oddities of nature', Huias were very attractive and many specimens were caught. New Zealand museums alone possess 119 skins. Apart from hunting, other causes of their decline may have been competition for food with introduced birds. These introductions may also have infected the huias with diseases to which they had no natural immunity. Habitat loss, which proved fatal for so many other New Zealand birds, also had its disastrous effect on this species. By 1888 the Huia was still recorded as being quite common. The last reliable sighting dates from 1907. It probably survived for several more years. Reports of black birds with orange facial wattles were occasionally heard until the 1920's.  Huia (female). Photograph by Rosamond Purcell from Swift as a Shadow. © 1999. The museum collection The National Museum of Natural History possesses seven Huiaskins. Two of these, beautifully mounted in a case, are typical for the way 19th-century collectors displayed these remarkable birds. Three skins are donations by other museums: two from the Wellington Museum in New Zealand and one from the Godeffroy Museum in Hamburg. The provenance of two more specimens is unknown; they were bought at an auction in England at about 1980 and sold to the museum in 1981.  Huia (female and male). Photograph by Rosamond Purcell from Swift as a Shadow. © 1999. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dr. L.W. van den Hoek Ostende |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 4, 2005 15:57:59 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 4, 2005 15:59:16 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Jun 9, 2005 12:09:52 GMT

Hi ! Heteralocha acutirostris:  Bye Alex |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 9, 2005 16:18:21 GMT

a good book to get on this species is  Flight of the Huia Ecology and conservation of New Zealand's frogs, reptiles, birds and mammals Kerry-Jayne Wilson Published April 2004 Paperback, 230 x 155 mm, 411 pp, colour photos and illustrations; ISBN 0-908812-52-3 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 9, 2005 18:23:06 GMT

Nga Huia  Tae a wairua te motu-huia, O Tara-rua I runga. (In spirit do I visit the groves of the Huia, on Tararua, those mountains to the south.) The Huia belongs to a family found only in New Zealand, a family so ancient that no relation is found elsewhere. Only the Moa and the Kiwi are likely to be more ancient. Before the arrival of Europeans it was already a rare bird, confined to the Ruahine, Tararua, Rimutaka and Kaimanawa mountain ranges in the south east of the North Island. The Huia was a bird of deep metallic, bluish-black plumage with a greenish iridescence on the upper surface, especially about the head, not unlike the Tui. The tail feathers were unique among endemic birds in having a broad white band across tips. At the base of the bill, on either side of the mouth hung the fleshy wattles characteristic of the family Callaeidae which were bright orange in the Huia. In both sexes the bill colour was ivory white and the legs were bluish grey. In size the Huia were slightly larger than the introduced Australian magpie. But the most remarkable feature of the species was the marked difference in size and shape of the bill and this difference was so extreme to cause early ornithologists, such as the renowned John Gould, to think that the male and female belonged to different species. The male's bill was stout and about 6cm long and curved slightly downward while the female's was slender, about 8.5 cm long, and very markedly curved downwards. The Huia relied mainly on insects for their food, especially those living in wood or under bark such as the abundant huhu beetle grub, Prionoplus reticularis. It has generally been supposed that the differences in the bills arose as an adaptation to reduce competition for food within the species as the male used his bill as a chisel to break up rotten wood and to widen insect holes while the female used hers as a probe so each was able to obtain food inaccessible to the other. However many scientists are not happy with the explanation as this great difference in form and function has not occurred in any other species. The Huia, above all other species in the forest, was sacred to Maori. It was, according to Phillips in his Book of the Huia, closely associated with the great chiefs of the land and only chiefs of distinction could properly wear its tail feathers, that is until the coming of the Pakeha broke down the importance of individual tapu and chiefly rank. Also the head and beak and skinned birds were often used as ear adornments and the ancient war plume, marereko, consisted of twelve Huia feathers. The feathers, when not in use, were kept in ornately carved boxes called Waka Huia. However, the rewards offered by collectors incited Maori to hunt the bird, which were traded and eventually sold to collectors in Europe and the United States. Sir Walter Lawry Buller, New Zealand's first ornithologist of note, who was deeply involved not only in the efforts to protect the bird but also in the trade to collectors, reports on one of his many expeditions in search of the Huia; "In the summer of 1867, accompanied by a friend and two natives, I made an expedition into the Ruahine ranges in search of novelties… While thus engaged, we heard the soft flute-like note of the Huia in the wooded gully far beneath us. One of our native companions at once imitated the call and in a few seconds a pair of beautiful Huias, male and female, appeared on the branches near us. They remained gazing at us only a few instants and then started off up the side of the hill, moving by a succession of hops, often along the ground, the male generally leading. Waiting 'till he could get both birds in line, my friend at length pulled the trigger." However, the final blow to the Huia undoubtedly came with the visit to New Zealand of the Duke and Duchess of York to Rotorua at the turn of the century. At the great welcome given to the royal party by Maori, one of the guides removed the huia feather from her own hair and placed it in the band of the bowler hat of the Duke. This simple act increased the demand for Huia feathers a hundredfold. Long after the royal guests had gone the demands for the feathers grew.  Avon Fine print limited (2000) edition (1984) facsimile reproduction of John Gould's Huia, Neomorpha Gouldii, from Birds of Australia. Folio size.(14 x21 inches, 552x356mm, approximately). Available at narena@nzbirds.com  www.nzbirds.com/Huia.html www.nzbirds.com/Huia.html |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Nov 5, 2005 3:59:58 GMT

HUIA Huia (Heterolocha acutirostris) is a species belonging to the endemic family of wattle birds, which also includes the saddleback (Philesturnus carunculatus) and the kokako, or New Zealand “crow” (Callaeas cinerea). All three species are characterised by the possession of fleshy wattles at the base of the bill and all three have proved to be extremely sensitive to the changes that have occurred in their environments since European settlement. The numbers and range of the once widely spread saddleback and kokako have become severely reduced, but the huia, whose original distribution was limited to the eastern part of the southern half of the North Island, is believed to have been extinct since the first decade of the present century. Hunting by European and Maori has been blamed for this extinction, but it is probable that destruction or modification of the forests in which the huia lived has played at least an equally important part in its disappearance. The most remarkable feature of the huia was the great difference between the sexes in the size and shape of the bill. That of the female was long, slender, and strongly curved into a sickle shape; that of the male was stouter, not so strongly curved, and only about two-thirds the length of the female's. The more powerful organ of the male permitted it to obtain insect larvae in soft or decaying wood in a manner similar to a woodpecker's, whereas the probe-like nature of the female's bill enabled her to reach larvae in holes and crevices. Spiders and fruits were also eaten. In size huias were about as big as Australian magpies, and their plumage was wholly greenish black, except for a broad white band across the tip of the tail; the bill was ivory white, the wattles orange, and the legs and feet bluish-grey. Flight was weak, the birds progressing best by rapid and powerful bounds. Their calls have been described as a soft whistle, a low chirping, and a loud shrill whistle of alarm, from which the species gets its Maori name. Little is known of nesting habits. Two to four dark-spotted stone-grey eggs were laid in a large nest built fairly close to the ground. Perhaps because of the unique differences between the bills of the two sexes, or because they were never abundant, huias were important to the Maori – their feathers (especially those of the tail) being used as adornments by chiefs. Beautifully carved boxes, waka-huia, were made and used solely for the storage of feathers.  |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 5, 2005 21:52:01 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Nov 6, 2005 20:54:10 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 7, 2005 7:30:00 GMT

gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 1, 2006 21:58:54 GMT

another pic from my computer |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 31, 2006 11:49:47 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 31, 2006 16:19:13 GMT

New Zealand Extinct Birds Brian Gill and Paul Martinson |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 6, 2007 17:50:34 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Feb 6, 2007 20:59:15 GMT

Christchurch Museum, NZ. The Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) was a bird endemic to New Zealand. It is now extinct, with no reliable sightings since W.W. Smith saw three birds in the Tararua Ranges on 28 December 1907. The bird had blue-black plumage, bright orange wattles at the gape and white-tipped tail feathers. It was the only bird known in which the bills of the male and female were radically different. The male's beak was short (approximately 60 mm) and straight while the female's beak was long and curved (up to 100 mm), a striking example of sexual dimorphism. Huia had been little studied by Western naturalists before they were driven to extinction. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huia flickr.com/photos/incognita_mod/377977725/ |

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Mar 18, 2007 17:55:25 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 23, 2007 17:22:07 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Aug 18, 2007 10:56:41 GMT

Extinct A large crow-like songbird confined to the dense forests of southern North Island in New Zealand. Peculiar for its unique sexual difference in bill shape: the male had a short and thick straight bill and was able to stab rotting trees to get access to grubs, while the female had a long and narrow curved bill enabling it to enter small holes to reach wood-boring insects. They mostly travelled in pairs, helping each other to get food. The bird was probably not uncommon when the first European settlers colonised the country, even though the Maori's, arriving some 800 years earlier, used its bicoloured tail-feathers as head-dresses for their chiefs. The arrival of settlers apparently led to greater catches of Huia's, partly because of greater demand by the Maori's and partly because skins were exported. Buller (1888) reported that 646 birds were killed on one site within a few days. Introduced predators and collecting for natural history cabinets reduced the number further, and by the 1890s the bird was decidedly rare. The last reliable observation were two males and a female seen in late Dec 1907, though unsubstantiated (but probably genuine) reports of sightings persist until 1923 and rumours of observations up to the 1960s (Phillipps 1963). Now, some 120 specimens in museums in New Zealand and probably a hundred more elsewhere is all what remains. Items in the ZMA - 5 birds: ZMA 4 & 5 Adult females, undated [before 1880], 'New Zealand', 'Neomorpha gouldi', old former mounts. ZMA 3413 Adult male, undated [1867-1890], 'New Zealand', bought from G.A. Frank Jr. (London), skin. ZMA 3612 Adult female, undated, 'South Island', New Zealand, presented by G.M. Mathews, skin. ZMA 3613 Adult male, undated, 'New Zealand', ex Museum Boucard, presented by G.M. Mathews, skin. Remarks As the species was only known from North Island, the provenance 'South Island' of ZMA 3612 is remarkable but probably wrong. Though the bird came from Mathews, this author made no comments on the label, and also in Mathews (1927) he listed only 'North Island'. 145.18.162.30/zma3d/detail.php?id=439&sort=taxon&type=family |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 31, 2008 13:29:54 GMT

Amonst the Maori of New Zealand, ornamental feathers were worn by both sexes. The feathers of the huia bird were especially popular. The huia is now extinct, but in the past its tail feathers were worn by chiefs on the head as a sign of rank. The entire carcass of a huia was sometimes worn suspended from the ear. Huia feathers were also used for decorating the dead. www.prm.ox.ac.uk/LGweb/feathers/1887_21_1.htm |

|