|

|

Post by Melanie on May 31, 2005 14:30:31 GMT

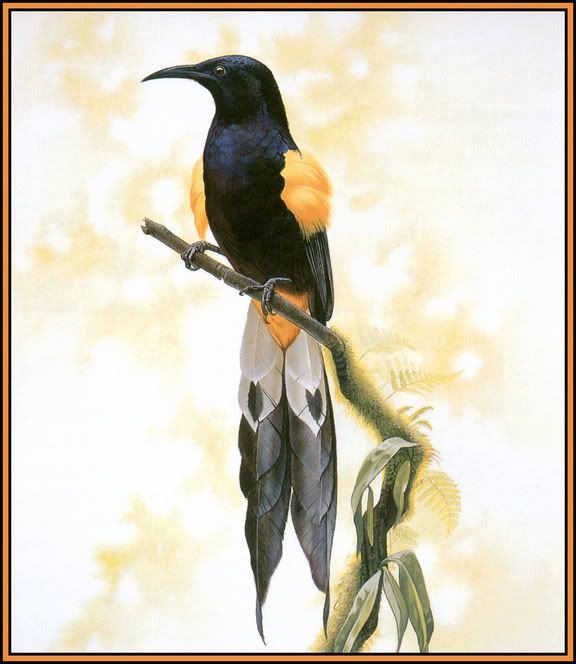

HAWAI'I 'O'O (Moho nobilis) Ex Formerly Endemic to Hawai'i only. Last seen in about 1934 on the slopes of Mauna Loa. The Hawaiian name 'O'O was an impression of the birds loud echoing call, "oh-oh". Similar to Bishop's 'O'o but with jet black glossy plumage and white outer tail feather bases. Also exhibited yellow axillary tufts and undertail like Bishop's 'O'o. Bill long and decurved. When perched the species apparently jerked its tail up and down. Sexes alike. (12 inches) Call / Song: A loud, harsh "oh-oh". Habitats used by the species were similar to the other 'O'o's. Although rumours persisted in the early 1980's that the species was still in existence there have been no confirmed sightings and it is unlikely that the species is still extant. H.W. Henshaw (1903) recorded that "even as late as 1898 hunters took a thousand 'O'o's in the woods north of the Wailuku" (Fuller 2000). Probably became extinct as a result of disease and predation, as well as habitat loss.  |

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Jun 7, 2005 6:42:19 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 12:02:59 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 8, 2005 5:36:48 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 7, 2005 7:06:57 GMT

gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Dec 18, 2005 0:47:31 GMT

Feathers in robes

Feathers of the Hawaii o'o Moho nobilis ( Merrem, 1786) can be found in various ethnological collections. They were used in the robes of the ancient kings and princes of Hawaii. Thousands of birds had to be plucked for these royal garments. After they had 'donated' their feathers, the birds were said to be released. But whether all were returned to the wild is doubtful. According to Scott Burchart Wilson and Arthur Humble Evans, who compiled an extensive work on Hawaiian birdlife, o'os fried in their own fat were considered a delicacy. The local feather industry probably was not the primary cause of extinction of the o'os. This tradition had been common practice for generations, and still o'os were numerous when Europeans settled on the islands. It is more likely that environmental changes, such as deforestation, caused the demise of the bird. The last reliable sighting of an Hawaii O'o dates from 1934.

The museum collection

Skins are preserved in museums in Brussels, Tring, Paris, Stockholm, Berlin, Dresden, New York, Los Angeles and Honolulu. One of the two skins in the National Museum of Natural History is from the private collection of C.J. Temminck. The bird was collected at the end of the 18th or the beginning of the 19th century. The other specimen was obtained in 1892 and donated to the museum by S cott Burchart Wilson in 1911.

|

|

|

|

Post by Meakia'i on Dec 21, 2005 20:04:32 GMT

The accidental introduction of mosquitoes to Hawai'i in the 1820's (I think) also served to deplete native populations of birds. They served as carriers of diseases that the birds had no immunities to such as Avian Pox, and Avian Malaria. It is partly for that reason, along with habitat loss, that virtually no native forest birds are found in low elevations today. Even now, a Hawaiian honeycreeper infected with one of those diseases is likely to die.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebastian on Oct 26, 2006 1:52:24 GMT

"Hawaii Oo were one of the most spectacular native birds. They were aggressive birds at the top of the dominance Hierarchy of nectarivores and displaced Iiwi, Hawaii Mamo, and Apapane from nectar sources (Perkins 1903).

Once widely distributed throughout the forests on Hawaii, Hawaii Oo were commonly found from 400 to 1200 m elevation (Wilson and Evans 1890 - 1899), with seasonal moviments to 1800 m (Rothschild 1893 - 1900). Perkins (1893) noted that they occurred mostly from 500 to 900 m elevation, inhabited ohia and koa-ohia forests, but deserted forests opened up by cattle. Hawaii Oo had disapeared by 1896 from the Puu Lehua area in Kona (Banko 1980 - 1984).

Records of this species occurring seasonally in the mamane forests of the Mauna Kea-Mauna Loa saddle (Wilson and Evans 1890 - 1899) suggest that they may have exploited the rich nectar sources in that forest by daily movements up the mountain, similar to de mass movements still seen for Iiwi and Apapane (Baldwin 1953; MacMillen and Carpenter 1980; C. B. Kepler and J. M. Scott, pers. observ.).

Hawaii Oo were very common during the 1800s, and as late as 1898 more than 1000 were collected for the feather trade above Hilo (Hen-shaw 1902). By the tur of the century, they had decreased drastically (Perkins 1903). There have been numerous unverified records during the 1900s with several reports even into the 1970s on windward Mauna Kea, but none by trained biologists (Banko 1980 - 1984). We failed to sight Hawaii Oo or other unidentified black birds on Hawaii.

Hawaii Oo apparently seldom sang (Perkins 1903) but had a very loud and distinctive call uttered frecuently before 09:00 that could be heard at great distances. Perkins (1903) Heard the call from 800 m away and describe it as "unlike that of any native bird and no one who has once heard it and identified it can ever again be in doubt as to the bird." This species was very active, "constantly on the move from tree to tree, hardly ever at a less height than [30 m] from the ground" (Wilson and Evans 1890 - 1899).

These descriptions of the behavior contrast with others that these were the most timid and wary of forest birds and flew off as soon sa a human was sighted (Munro 1944:: 87). Based on the descriptions in the literature and our experience with Kauai Oo, we estimated the effective detection distance for Hawaii Oo to be 75 m. The chances of our having overlooked a population of 100 birds in the study areas on Hawaii are small."

Book: "Forest Bird Communities of the Hawaiian Islands: Their Dynamics, Ecology, and Conservation" - J. Michael Scott - 1986 - Publication of The Cooper Ornithological Society.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebastian on Jun 11, 2007 20:11:13 GMT

Hi! New pic!!!  Bye! |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 31, 2008 13:34:49 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 21:38:43 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 28, 2008 6:49:50 GMT

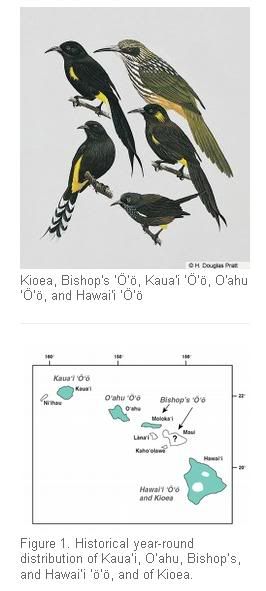

Editor's Note: This account covers the 4 species of ‘Ö‘ö in the Hawaiian Islands, plus the closely-related Kioea. Future revisions of this account may provide separate coverage for each species. This large, interesting, and diverse family of nectar-feeding honeyeaters has its center of abundance in the Australo-Papuan region and was represented in the Hawaiian Islands by 5 species: Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö (‘Ö‘ö ‘ä‘ä) on the island of Kaua‘i, O‘ahu ‘Ö‘ö on O‘ahu, Bishop’s ‘Ö‘ö on Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i ‘Ö‘ö and Kioea on Hawai‘i. The Hawai‘i ‘Ö‘ö was the first Hawaiian honey-eater discovered by westerners, described from a specimen obtained in 1779 during Captain James Cook’s third voyage; the other 4 species were not known to the scientific community until the mid- to late 1800s. The O‘ahu and Hawai‘i ‘ö‘ö and the Kioea are now definitely extinct, and the Kaua‘i and Bishop’s ‘ö‘ö are probably extinct. These medium-sized to large passerines have relatively slender, sharp, slightly down-curved, dark bills and specialized tubular tongues that function as straws for sucking nectar from many structurally different species of flowers. All 4 ‘ö‘ö have black plumage with discrete bright-yellow patches and feather-tufts, and 3 have distinctive color patterns on their graduated tail-feathers; the Kioea has a streaked head, neck, upper back, and underparts, a black mask through the eye, and uniformly colored brown wings, lower back, and long graduated tail. The bright-yellow ‘ö‘ö feathers were prized by early Hawaiians and used in making long flowing cloaks, opulent feather capes, ornate headdresses, and royal standards (kahili) of the kings and high chiefs, as well as numerous leis and other items. Yellow ‘ö‘ö feathers were also gathered into small, loosely tied bunches as tax payments by common people to the ruling class. All 5 of these honeyeaters were inhabitants of undisturbed native forests. They were highly vocal, having loud, distinct, pleasant, melodious repertoires. Only the voice of the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö was ever recorded, archived, and published, and it is probably the only Hawaiian honeyeater that has been heard by anyone now living. Except for the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö, most of our knowledge of these species is anecdotal; 3 of the 4 ‘ö‘ö species disappeared shortly after they were described. Much of the specimen material has little or no data, and only 10 O‘ahu ‘Ö‘ö and 4 Kioea study skins are known to exist in collections. Exam-ination of a series of specimens and attached labels has revealed some unpublished information, herein presented for the first time. The disappearance of Hawaiian honeyeaters was not well documented, but possible causes have been widely discussed. With the exception of hurricanes and other severe storms, negative factors contributing directly or indirectly to their extinction were related to the activities of native Hawaiians and Caucasians since their first contact with the islands. Negative factors have included destruction and modification of native forests; introduction of nonnative mammals to the islands (rats, Indian mongoose, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, domestic cats) and their impacts on native forest habitats, as well as directly on the birds themselves; introduction of nonnative birds and associated diseases; introduction of mosquitoes; and exploitation of the ‘ö‘ö for feathers. We dedicate this account to our longtime friend and colleague John L. Sincock, who died in 1991 at his home in Pennsylvania. John, a Research Wildlife Biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, studied birds in Hawai‘i (including the Leeward Islands) from 1967 until his retirement in 1984. He pioneered research on Hawaiian forest birds, particularly on Kaua‘i, and spent thousands of hours in the Alaka‘i Swamp. He found the first Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö nest in 1971 and, subsequently, 2 others. Assisted by his wife, Renate, he secured the first photographs of the Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö on 31 May 1971. He subsequently took between 300 and 400 color and black-and-white photos and several hundred feet of color super-8 motion picture film of Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö in the Alaka‘i Swamp in the 1970s and made sound recordings in the early 1980s. John introduced all 4 of us to the Alaka‘i Swamp, enabling us to personally observe and hear what is believed to have been the last Kaua‘i ‘Ö‘ö. We rely on much of his unpublished data in this paper. In this account, if a species is not listed under a given topic, no information is known to exist on that subject for that species. Nouns in the Hawaiian language are both singular and plural. For museum abbreviations, see Appendix 1 . bna.birds.cornell.edu |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 14, 2008 6:33:55 GMT

Hawaii’s honeyeater birds tricked taxonomists DNA from old museum specimens reveals evolutionary look-alikes By Susan Milius Web edition : Friday, December 12th, 2008 Five species of Hawaiian birds have made fools of taxonomists for more than 200 years, thanks to a fine bit of evolutionary illusion-making.O‘o and kioea birds, now extinct, specialized in feeding on flower nectar using long, curved bills and split tongues tipped with brushes or fringe. Since Captain Cook’s expedition introduced the birds to western science, they have been classified in the honeyeater family with similar-looking nectar sippers living in New Guinea and Australia.DNA from museum specimens of the Hawaiian species shows that the birds weren’t a kind of honeyeater at all, according to Robert Fleischer of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Instead the Hawaiians’ resemblance to the western Pacific birds offers a new and dramatic example of how evolution within different lineages can converge on similar forms for similar jobs, he and his colleagues report online December 11 in Current Biology.O‘os and the kioea weren’t even closely related to the honeyeaters of the western Pacific, Fleischer says. The closest relatives of Hawaii’s so-called honeyeaters were waxwings, silky flycatchers and the palmchat. These kin live mostly in the Americas and use tongues of unexciting shapes to eat bugs and berries. In the United States, the cedar waxwing and the Southwest’s phainopepla may be the best-known examples.“It’s like we had this animal we always thought was a dog, and it’s turned out to be a mongoose,” Fleischer says.Genetic evidence suggests that some ancestral relative of the waxwing group arrived in Hawaii between about five and 14 million years ago, Fleischer says. Living the island life, the ancestral birds shifted to nectar feeding and evolved body forms like the honeyeaters. All the birds with similar shapes and habits looked like kin to ornithologists.Their degree of convergence is “remarkable,” in the words of Keith Barker of the University of Minnesota’s Bell Museum in Minneapolis. He’s working with DNA that uncovered another long-lost relative of the waxwings, living among southeast Asian birds. “This was shocking to us, but not nearly as startling as Fleischer's finding,” he says.Discovering the mainland connection for Hawaii’s o‘os and kioea adds yet another animal group to the list of immigrants from the Americas that colonized Hawaii, Barker says. Yet, excepting the mints and silverswords, a lot of Hawaii’s plants seem to have come from the opposite direction, from the South Pacific.While living in Hawaii, the new nectar feeders diversified into four o‘o species, each on a different island, with the kioea residing on the Big Island.Lemon- colored patches in o‘o plumage supplied brilliant yellow feathers for island royalty’s ceremonial capes and headdresses.The kioea disappeared first, during the 1850s. O‘os hung on longer. The last of the species, Kauai’s, hasn’t been seen since 1985. “I just missed it,” says Fleischer, who moved to Hawaii that year.Kioeas and o‘os deserve a family of their own, Fleischer and his colleagues contend. Thus, even before it was named, the newly christened Mohoidae became the only bird family that disappeared without a survivor in the last hundred years. www.sciencen ews.org/view/ generic/id/ 39312/title/ Hawaii%E2% 80%99s_honeyeate r_birds_tricked_ taxonomists |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 14, 2008 6:43:59 GMT

Two Hawaiian, nectar-feeding birds, the kioea (brown-streaked, in middle) and an o‘o species (lower left), looked so much like nectar specialists from the western Pacific (two species on right) that taxonomists put them all in the same honeyeater family. The Hawaiian birds are now extinct, but DNA evidence shows that the resemblance came from convergent evolution, and the Hawaiians were actually much closer to birds from the Americas, such as cedar waxwings (upper left). www.sciencen ews.org/view/ generic/id/ 39312/title/ Hawaii%E2% 80%99s_honeyeate r_birds_tricked_ taxonomists |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 25, 2008 10:13:46 GMT

Hawaii's Bird Family Tree RearrangedScienceDaily (Dec. 16, 2008) — A group of five endemic and recently extinct Hawaiian songbird species were historically classified as "honeyeaters" due to striking similarities to birds of the same name in Australia and neighboring islands in the South Pacific. Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution, however, have recently discovered that the Hawaiian birds, commonly known as the oo's and the kioea, share no close relationship with the other honeyeaters and in fact represent a new and distinct family of birds—unfortunately, all of the species in the new family are extinct, with the last species of the group disappearing about 20 years ago. The findings of the study, conducted by Robert Fleischer, a molecular geneticist at Smithsonian's National Zoo and National Museum of Natural History and Storrs Olson and Helen James, both curators of birds at the National Museum of Natural History, were published in the international science journal Current Biology Dec. 11. "The similarities between these two groups of nectar-feeding birds in bill and tongue structure, plumage and behavior result not from relatedness, but from the process of convergent evolution—the evolution of similar traits in distantly related taxa because of common selective pressures," said Fleischer, lead author of the study. These five Hawaiian species of birds in the genera Moho and Chaetoptila, looked and behaved like Australasian honeyeaters of the family Meliphagidae, and no taxonomist since their discovery on Captain James Cook's third voyage to Hawaii in 1779 has ever classified them as anything else. However, there has been no rigorous assessment of their relationships using molecular data—until now. Smithsonian scientists obtained DNA sequences from museum specimens of Moho and Chaetoptila that had been collected in Hawaii 115-158 years ago. Analyses show that these two Hawaiian genera descended from a common ancestor. Surprisingly, however, the analyses also revealed that neither genus is a meliphagid honeyeater, nor even in the same part of the evolutionary path of songbirds as meliphagids. Instead, these Hawaiian birds are divergent members of a group that includes deceptively dissimilar families of songbirds (waxwings, neotropical silky flycatchers and palm chats). The researchers have placed these birds in their own new family, the Mohoidae. "This was something that we were not expecting at all," said Fleischer. "It's a great example of how much we can learn about systematics and evolution by applying new technologies like ancient DNA analysis to old museum specimens." A DNA rate calibration suggests that these Hawaiian taxa diverged from their closest living ancestor 14-17 million years ago, coincident with the estimated earliest arrival of a bird-pollinated plant lineage in Hawaii. Convergent evolution is illustrated well by nectar-feeding birds, but the morphological, behavioral and ecological similarity of Moho and Chaetoptila to the Australasian honeyeaters makes these groups a particularly striking example of the phenomenon. All five members of the family Mohoidae were medium-sized songbirds with slender, slightly downward curved bills with unique scroll-edged and fringed tongues, making them very specialized nectar-feeding birds. They inhabited undisturbed forests on most of the main Hawaiian islands. Although the cause for the extinction of the Mohoidae species is not definitely known, disease, human development and introduced species like mosquitoes, mongooses and rats are thought to play a significant role. The last member of the family Mohoidae to be positively identified was a Kauai o'o (Moho braccatus) in the Alakai Swamp on Kauai in 1987. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/12/081211121827.htm

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on May 27, 2009 20:03:19 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by RSN on Sept 1, 2011 13:26:02 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Nov 27, 2015 23:52:34 GMT

Rice, Paul, and Mayle, Peter (1981). As Dead as a Dodo |

|

|

|

Post by koeiyabe on Dec 12, 2015 13:54:25 GMT

"The Earth Extinct Fauna (in Japanese)" by Tadaaki Imaizumi (1986) |

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 19, 2016 10:33:05 GMT

|

|