Post by Carlos on Mar 11, 2006 18:51:48 GMT

Cabrera (1932), second part of my translation of the Barbary Lion account:

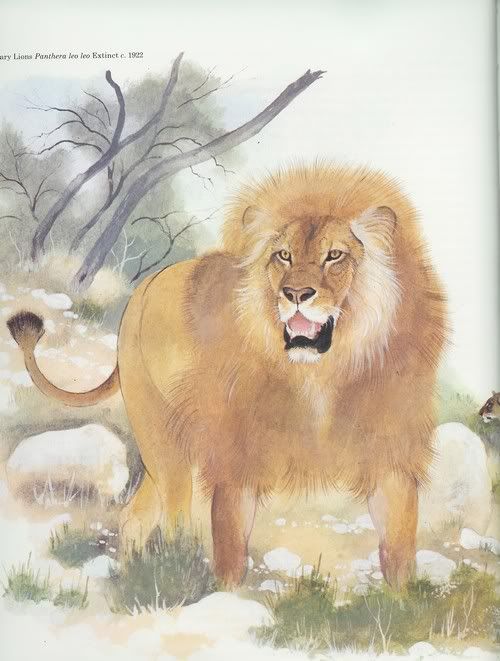

… It is evident that the Barbary lion was known for its enormous size and for showing a very thick hair fringe from the mane down to the groin. This latter characteristic was also present in the Cape lion (L. l. melanochaitus H. Smith), judging by Cornwallis Harris’ drawing (1841), the only reliable figure of this race, as it was made in a time when there were still lions south of the River Orange; it seems that this subspecies did reach also a very big size, up to ten and a half feet of total length, which is almost as big as the Tunisian lion at Leyden museum. Lions from the equatorial zone in Africa never show the ventral hair fringe and the bigger ones always measure less than three meters, including the tail. For those who are interested in the study of speciation this is a very suggestive fact, the coincidence of characters in two geographic forms that occupy the opposite extremes of the continent at about the same distance from the Equator and with certain climatic affinities.

Distribution: the Barbary lion can be considered today as an extinct subspecies, but less that a century ago it was found almost all over Morocco and if it truly has completely disappeared from this country it has been from very few years ago, as according to captain Peyronnet, at about 1922 there were still notices of its presence in forests in the Middle Atlas, where it seem to have had its last stronghold.

…

Both in Tunisia and in Algeria they were finally exterminated forty years ago. J. A. Allen has designated Constantine as the type locality for this subspecies.

…

The quick disappearance of this famous carnivore from Moroccan territory is one of the most curious problems in relation to the fauna of that country. It is understandable that after two centuries of colonization by two European nations as active and intrepid as the English and the Dutch, the lions of the Cape Province became exterminated and it is also understandable its absence from Algeria, where the French domination brought daring hunters like Gerard, Bombonnel and Chasaign, that in no time cleaned certain districts of these animals; but in no way it is possible to understand the reason why in less than a century the lion has become extinct in a country like Morocco, uncultivated an wild until twenty five years ago, and whose inhabitants are far to be a people of hunters and where, because of the lack of safety, very few Europeans ventured looking for hunting emotions.

Judging by the information given in their classic books by León Africano and Luis de Mármol Carvajal, Morocco used to be a real land of lions. The second of those authors stated [in 1573] that there were lions in great numbers in the Rif Mountains, adding that «los que se crían en tierra de Temecena y de Fez, y en el desierto de Angued junto a Tremecen … son los mas brauos y crueles de toda Affrica [those around Temecen and Fez and in the desert of Angued near Tremecen … are the wildest and cruellest of all Africa] ». The Angued desert referred by Mármol is the Angad Plain, between the lower Mouluya and the Algerian border. Still in the middle of the XVIIth century, the lion was abundant in the Mediterranean coast, so that Christian knights from the Spanish cities in Africa went around hunting them for sport …

In the XVIII century there were many lions near Larache, Mazagan and Mekinez; the Histoire Générale des Voyages (1747) refer the lion encounters of the fleeing Christian captives from those cities. At the end of that century, the range of the lion reached Cape Nun (Sugnier 1784).

Still in 1839, when Drummond Hay made the journey referred to in his work Morocco, its wild tribes and savage animals, there were many lions left in Guelaya and in the Mamora Forest, and the botanists Hooker and Ball tell that less than twenty five years before their trip to the Great Atlas, that’s it around 1846, one was killed at Yebl Kebir, near Tangiers; but not many yeas later, the king of the beasts had left the Mediterranean coast in the [Moroccan] Empire. According to the data collected by me from old native hunters from the Rif and from Yebala, around 1880 there were no lions left north of the Lower Bu Regreg and north of the Taza Gorge. Few years later, Muley Hassan made many forests in the Middle Atlas burn to get rid of lions and bandits, and no doubt, this measure together with the civil wars that raged after the dead of that illustrious sultan, contributed to de disappearance of the lions.

… It is evident that the Barbary lion was known for its enormous size and for showing a very thick hair fringe from the mane down to the groin. This latter characteristic was also present in the Cape lion (L. l. melanochaitus H. Smith), judging by Cornwallis Harris’ drawing (1841), the only reliable figure of this race, as it was made in a time when there were still lions south of the River Orange; it seems that this subspecies did reach also a very big size, up to ten and a half feet of total length, which is almost as big as the Tunisian lion at Leyden museum. Lions from the equatorial zone in Africa never show the ventral hair fringe and the bigger ones always measure less than three meters, including the tail. For those who are interested in the study of speciation this is a very suggestive fact, the coincidence of characters in two geographic forms that occupy the opposite extremes of the continent at about the same distance from the Equator and with certain climatic affinities.

Distribution: the Barbary lion can be considered today as an extinct subspecies, but less that a century ago it was found almost all over Morocco and if it truly has completely disappeared from this country it has been from very few years ago, as according to captain Peyronnet, at about 1922 there were still notices of its presence in forests in the Middle Atlas, where it seem to have had its last stronghold.

…

Both in Tunisia and in Algeria they were finally exterminated forty years ago. J. A. Allen has designated Constantine as the type locality for this subspecies.

…

The quick disappearance of this famous carnivore from Moroccan territory is one of the most curious problems in relation to the fauna of that country. It is understandable that after two centuries of colonization by two European nations as active and intrepid as the English and the Dutch, the lions of the Cape Province became exterminated and it is also understandable its absence from Algeria, where the French domination brought daring hunters like Gerard, Bombonnel and Chasaign, that in no time cleaned certain districts of these animals; but in no way it is possible to understand the reason why in less than a century the lion has become extinct in a country like Morocco, uncultivated an wild until twenty five years ago, and whose inhabitants are far to be a people of hunters and where, because of the lack of safety, very few Europeans ventured looking for hunting emotions.

Judging by the information given in their classic books by León Africano and Luis de Mármol Carvajal, Morocco used to be a real land of lions. The second of those authors stated [in 1573] that there were lions in great numbers in the Rif Mountains, adding that «los que se crían en tierra de Temecena y de Fez, y en el desierto de Angued junto a Tremecen … son los mas brauos y crueles de toda Affrica [those around Temecen and Fez and in the desert of Angued near Tremecen … are the wildest and cruellest of all Africa] ». The Angued desert referred by Mármol is the Angad Plain, between the lower Mouluya and the Algerian border. Still in the middle of the XVIIth century, the lion was abundant in the Mediterranean coast, so that Christian knights from the Spanish cities in Africa went around hunting them for sport …

In the XVIII century there were many lions near Larache, Mazagan and Mekinez; the Histoire Générale des Voyages (1747) refer the lion encounters of the fleeing Christian captives from those cities. At the end of that century, the range of the lion reached Cape Nun (Sugnier 1784).

Still in 1839, when Drummond Hay made the journey referred to in his work Morocco, its wild tribes and savage animals, there were many lions left in Guelaya and in the Mamora Forest, and the botanists Hooker and Ball tell that less than twenty five years before their trip to the Great Atlas, that’s it around 1846, one was killed at Yebl Kebir, near Tangiers; but not many yeas later, the king of the beasts had left the Mediterranean coast in the [Moroccan] Empire. According to the data collected by me from old native hunters from the Rif and from Yebala, around 1880 there were no lions left north of the Lower Bu Regreg and north of the Taza Gorge. Few years later, Muley Hassan made many forests in the Middle Atlas burn to get rid of lions and bandits, and no doubt, this measure together with the civil wars that raged after the dead of that illustrious sultan, contributed to de disappearance of the lions.