|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Feb 5, 2005 9:48:42 GMT

Not seen since the beginning of the 20th Century.

The name NUKUPU'U translates in Hawaiian as "bill shaped like a hill", nuku = bill of a bird, pu'u = a small round hill.

Males were bright yellow below and on the head and face with pale olive-green upperparts and a short olive-colored tail. Undertail-coverts were whitish. The eye was dark with a small dark surround/loral area; pale upper mandible surround. The fantastic bill had a sharply decurved upper mandible and a short decurved lower mandible. Females were duller, being olive-green all over and with a shorter and less robust bill. The legs were dark. (5.5 inches) Calls: A loud "kee-wit". Song: Like 'Akiapola'au song but less vigourous - a melodious and warbling song with a rising whistle or trill at the end "pit-er-ieu".

The curved lower mandible, whitish undertail-coverts and pale upper mandible surround distinguish this species from 'Akiapola'au.

The species was a bark picker and fed in a similar way to 'Amakihi or 'Akikiki. It was also known to tap at bark in the manner of 'Akiapola'au but not as vigorously. Only occasionally was it reported to feed on nectar. The species inhabited dense, wet ohi'a forests.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jun 7, 2005 4:44:51 GMT

Last collected in 1837. Oahu Nukupu'u Hemignathus lucidus lucidus This subspecies was similar to the other subspecies of Nukupu'u found on Hawaii,Kauai, and Maui. The Oahu Nukupu'u had a thick head and short tail.The males had a bright yellow head with black lores.Females and immature birds had less yellow and shorter bills.The long down curved upper mandible was twice the length of the lower. The Oahu Nukupu'u was a bark picker and tapped the bark probing for insects.The species was said to only rarely feed on nectar. Its primary haunts were the wet Ohia lehua forests and the Koa forests at lower elevations.The song was described as being similar to the Akiapolaau and the House Finch. The call was a loud kee-wit. There are few specimens in collections. A German collector, Deppe shot several specimens about 1837 from Nuuanu Valley where it fed on honey from the flowers of the plantain. Perkins, the famous English collector, found evidence that it abounded in the Oahu forests in some numbers in 1860. None of the bird collectors in the 1890's found any trace of the Oahu Nukupu'u. There is very little information available about this species and only a few specimens in the world's museums .Like all of the other extinct native forest birds of Oahu ,as well as the few species that remain, the Nukupu'u populations were decimated by loss of habitat, introduction of alien bird species that competed with them for limited resources, the introduction of rats, cats, and mongoose which preyed on them, the arrival of mosquitos in 1827 that eventually gave the native birds Malaria, the arrival of the pox virus in Hawaii that spread to the birds and the collectors, who in some cases, shot the last of a species ever seen on Oahu. Many of the unique and beautiful native forest bird species of Oahu have already fallen into the abyss of extinction and the few remaining species continue their flight in the same direction. It is very important and urgent that more funds are made available to help the endangered native forest birds of Oahu survive. www.oahunaturetours.com/nukupuu.html |

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jan 12, 2006 21:33:17 GMT

The last confirmed sightings of this species were in 1995-1996 at Hanawi on Maui, but there have been no other confirmed sightings since then despite extensive effort in a large proportion of the historic range. However, it cannot yet be presumed to be Extinct until further surveys have confirmed that there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. Any remaining population is likely to be tiny, and for these reasons it is treated as Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct).

Family/Sub-family DREPANIDIDAE

Species name author Lichtenstein, 1839

Taxonomic source(s) AOU checklist (1998 + supplements), Sibley and Monroe (1990, 1993)

Identification 14 cm. Medium-sized honeycreeper with strongly downcurved "heterobill" in which mandible is half the length of maxilla. Kaua`i male golden-yellow on head and breast, shading to white on belly and undertail-coverts. Crown, nape, postocular line and posterior edge of ear-coverts slightly tinged greenish, yellowish-green upper-parts. Black lores, eye-ring, and bill. Kaua`i female greenish-grey above, mostly dull white below with yellow restricted to chin, upper throat, and supraloral patch. Maui male similar except greyer dorsally, darker on crown and nape, yellower on belly and undertail. Maui female similar but duller, more dark colouring on head producing prominent yellow superciliary. Similar spp. Kaua`i `Amakihi H. kauaiensis has paler bill, less head/back contrast, and dingier underparts. Maui Parrotbill Pseudonestor xanthophrys rather similar in plumage, but much heavier bill. Voice Song a short warble, call ke-wit, both similar to voice of `Akiapola`au H. munroi of Hawai`i.

Population estimate

Population trend

Range estimate (breeding/resident)

Country endemic?

<50

unknown

22 km2

Yes

Range & population Hemignathus lucidus is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands (USA). On Kaua`i, it is probably confined to the `Alaka`i Wilderness Preserve3,10 where it was apparently recorded a few times 1984-1998, although at least some, if not all, of these sightings appear to refer to H. kauaiensis1,8,14. Recent surveys on Kauai have failed to find it, and it seems likely to be extinct15,16. On Maui, it is found on the eastern and north-eastern slopes of Haleakala, where there have been several unconfirmed detections 1986-1998, although a single male seen in 1995 (seen by more than one qualified observer and backed up by detailed field notes8) in the same place as a report from 1994 provided strong evidence of its persistence1,8,9. There have been no other confirmed sightings since then despite extensive effort in a large proportion of the historic range: annual surveys by NPS, two State sanctioned surveys, monthly surveys in Hanawi, TNC surveys and efforts by the Maui Forest Bird Recovery team. Although not all of these programs surveyed locations where the species was last observed, many surveyed highly likely locations14,16. US Fish and Wildlife Service (in review) concluded that in all probability this species is extinct or functionally extinct. However, it should not yet be reclassified as Extinct until further surveys have confirmed that there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. If any population remains, it is likely to be tiny.

Ecology It inhabits dense, wet `ohi`a forest and the higher parts of mesic koa-`ohi`a forest6,10. On Maui, all recent sightings were between 1,450 and 2,000 m, mostly at the lower end of that range10. On Kaua`i, the Koai`e Valley (where it was seen in 19953,8) is at 1,000-1,300 m7. It feeds on wood-borers, spiders and beetles3,6,9,10.

Threats The lower-elevation koa forests (possibly the species's key habitat) have been nearly eliminated by cattle-ranching9. Remaining higher-altitude forests are degraded by introduced ungulates4,9,10,12. Feral pigs facilitate the spread of alien plants and introduced disease-carrying mosquitoes4,7. On Kaua`i, all bird populations appeared to have been drastically reduced after Hurricane Iniki in 19927, although some have since recovered. It has been extirpated from the koa-`ohi`a forests of Koke`e, suggesting that it is sensitive to perturbation. Other suggested limiting factors include predation and competition from exotic bird and insect species1,13.

Conservation measures underway On Maui, fencing and feral pig eradication has been completed in a c.650 ha area where the male was recorded in 19941,11. In Waikamoi Preserve, Hanawi Natural Area Reserve and Haleakala National Park, efforts have been made to combat the establishment of alien plants4,11. On Kaua`i, the Koai`e Stream area has been intensively managed to conserve Puaiohi Myadestes palmeri, and may have helped any H. lucidus that remain in the area3,13.

Conservation measures proposed Conduct surveys to locate any remaining populations. If any birds are found, attempt to increase the population by captive propagation10. Research competition from exotic bird and insect species5.

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jan 12, 2006 21:33:33 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by sebbe67 on Jan 12, 2006 21:34:19 GMT

Heavy losses The fact that the various species of Drepanididae or Hawaiian honeycreepers are not discussed separately but as a group, illustrates the heavy losses this family has suffered. Fifteen species are extinct and of the remaining species four subspecies have disappeared. Many of the surviving (sub)species are on the verge of extinction. Like the Darwin-finches of the Galápagos Islands, the Hawaiian honeycreepers show a wide range of feeding adaptations, as is illustrated in the highly specialized, very diverse beaks of the various species. Birds which extract honey from flowers or insects from holes and crevices in trees have long, thin and curved beaks, wheras the beaks of Drepanididae that live on various kinds of fruits or seeds are finch- or parrot-like. Several species played an important role in pollinating some of the endemic plants. Now that many Drepanididae have disappeared, some of these plants are also faced with extinction. The role of the birds has partly been taken over by volunteers, who, armed with brushes, scout the volcano slopes and carefully transport pollen from one plant to another. Museum specimens Most skins of Drepanididae in Naturalis were collected by Robert Perkins, a British ornithologist who lived on Hawai'i. They were donated to the museum on 13 February 1901 by Alfred Newton, chairman of “the joint commitee appointed by the Royal Society and British Association for Zoology of the Hawaiian Islands”. The donation existed of 19 skins and one nest. According to Newton it was a very valuable collection. In fact worth at least £ 30 ! The accompanying letter testifies the importance of the donation. Newton writes to Otto Finsch, curator of birds at the museum: "I hope the Birds will be appreciated, as I am sure they will be by you, as you are aware of the fact that the whole indigenous Fauna of the Islands is doomed to extinction, even the insects are rapidly disappearing ("Yes! and even the Landshells!!"). I do not say this to enhance the value of one little collection, but in the interest of science, that all possible care may be taken to keep the specimens for posteriority. Of some of these species I am confident it will never be in anybody's power to obtain more specimens. On the Island of Oahu Mr. Perkins estimates that one half of the species of birds originally inhabiting it, are already extinct, and some which were fairly common, are now hardly to be found, so rapid has been the change." Newton's pessimism proved to be justified. Around 1900 the Hawaii Mamo Drepanis pacifica, the Kona Grosbeak Chloridops kona, the nominate race of the Oahu Nukupuu Hemignathus lucidus lucidus and all forms of the Akialoa with the exception of the Greater (Kauai) Akialoa, Hemignatus ellisianus stejnegeri, were extinct. The Kauai Akialoa was last seen in the 1960s and is now also considered extinct. ip30.eti.uva.nl/naturalis/detail?lang=uk&id=7 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 16, 2008 9:35:34 GMT

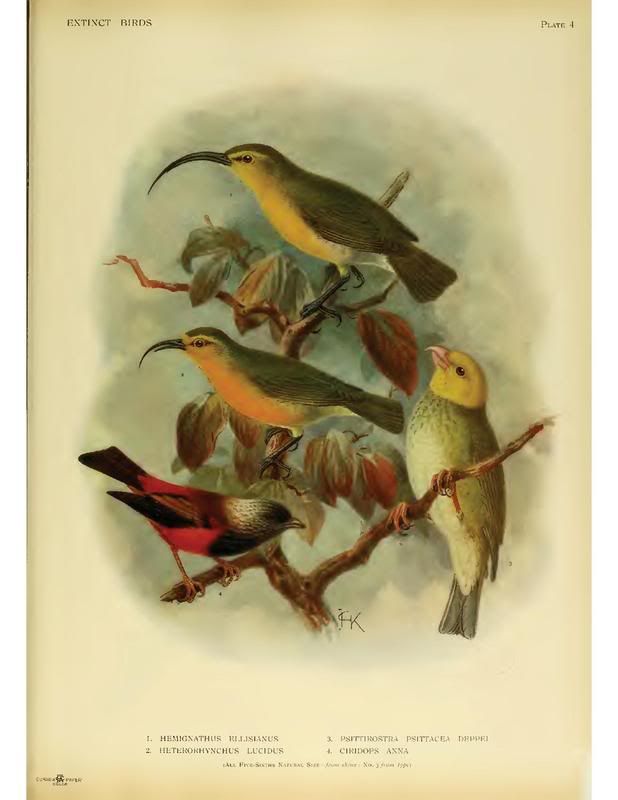

Extinct birds : an attempt to unite in one volume a short account of those birds which have become extinct in historical times : that is, within the last six or seven hundred years : to which are added a few which still exist, but are on the verge of extinction (1907) |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jul 25, 2008 6:23:29 GMT

Extinct birds : an attempt to unite in one volume a short account of those birds which have become extinct in historical times : that is, within the last six or seven hundred years : to which are added a few which still exist, but are on the verge of extinction (1907) |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Sept 13, 2008 17:47:39 GMT

According to H. Douglas Pratt ('The Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Drepanidinae') all three Nukupu'u's should be regarded full species.

The two species from Maui and O'ahu are closer related to the Akiapola'au thean to the Kaua'i Nukupu'u.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 20:10:43 GMT

According to H. Douglas Pratt ('The Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Drepanidinae') all three Nukupu'u's should be regarded full species. The two species from Maui and O'ahu are closer related to the Akiapola'au thean to the Kaua'i Nukupu'u. Thread been renamed |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 20:16:27 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 13, 2008 20:42:04 GMT

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Sept 15, 2008 9:39:24 GMT

O'ahu Nukupu'u ( Hemignathus lucidus) male below, female above  scanned from H. Douglas Pratt: 'The Hawaiian Honeycreepers, Drepanidinae |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Sept 16, 2008 8:10:42 GMT

Image reference: 35886 Title: Loxops coccinea rufa, Myadastes obcurus oahuensis, Psittirostra psittacea Description: Hemignathus lucidus, Hemignathus ellisianus, Moho apicalis. Birds (listed from top to bottom) native to the Hawaiian Islands, many now extinct. Illustration by Julian Hume. piclib.nhm.ac.uk/piclib/www/image.php?img=81646&frm=ser&search=hume,%20julian%20pender |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Nov 28, 2008 7:28:28 GMT

Hawaiian honeycreepers, famous as an example of adaptive radiation on islands, include species that converge in their appearance and way of life on more familiar birds from continents. While some honeycreepers retain an ancestral finchlike form and life history, others resemble and behave like sunbirds, warblers, or nuthatches. In contrast to this convergence, evolution has drawn a few honeycreepers out on novel pathways. What more bizarre evolutionary tangents could one imagine than the ‘Akiapölä‘au and Nukupu‘u? In the absence of woodpeckers, these birds capture invertebrates living in bark or wood, but their tools and methods are entirely different. No other birds have, in a sense, evolved two bills in one. The long upper mandible curves downward like a black wiry hook, whereas the short, robust lower mandible juts forward as a sharp-pointed awl. The lower mandible is more or less straight in the ‘Akiapölä‘au, but curves with the upper mandible in the Nukupu‘u. Equipped with such tools, the tree-dwelling ‘Akiapölä‘au sets out foraging. Hitching its way along branches and twigs, the bird tests bark and epiphytes, pausing inquisitively to tap with the awl or probe with the hook. Once it detects a hiding caterpillar or spider, the bird goes to work excitedly. Noisily pounding and yanking, the ‘Akiapölä‘au excavates the substrate in pursuit of its retreating quarry. Ultimately the prey is cornered, hooked out into the open, and flogged against the bird’s perch before being gulped down. Perhaps their peculiar bills are unsuited to taking nectar, but whatever the reason, ‘Akiapölä‘au and Nukupu‘u usually ignore flowers. ‘Akiapölä‘au do drink sap from the small, shallow wells they drill in live bark. A bird selects a few individual trees for drilling and visits each repeatedly, so that eventually a large surface of the tree’s bark becomes peppered with holes. Drinking sap does not come easily for an ‘Akiapölä‘au, however, and requires the bird to tilt its head upward so that the fluid runs down inside the mandible guided by a short, fringed tongue. This recently discovered behavior resembles sap-sucking by woodpeckers. The bill of a young ‘Akiapölä‘au seems to take many months to grow and harden, and during this time the juvenile remains with its parents. Protected on the family’s large territory, the young bird slowly learns foraging skills. Generally only one young fledges, the sole offspring raised by its parents that year. The ‘Akiapölä‘au survives as an endangered species on its home island of Hawai‘i. Restricted to remnant forest above 1,500 m elevation, the total population numbers about 1,000 birds. Because the species prefers foraging on koa (Acacia koa), but nests almost exclusively in the crowns of ‘öhi‘a-lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), the best habitat includes both tree species. Factors limiting its population and distribution include mosquito-borne diseases and the loss and fragmentation of habitat. Depredation by feral cats (Felis catus) and rats (Rattus spp.) and depletion of its arthropod prey base by imported predatory and parasitic insects are likely threats. The Nukupu‘u inhabited forests on three islands—Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, and Maui—and each island supported its own subspecies. The island forms are so distinct that the Nukupu‘u may eventually be split into three species. A recent review of all Nukupu‘u records from the twentieth century revealed that this bird is probably extinct. On a more optimistic note, concern for the ‘Akiapölä‘au has resulted in habitat protection and restoration in key parts of its range. With expanded management as a metapopulation, the ‘Akiapölä‘au can be spared the fate of its less fortunate sister species. “Of all the native Drepanid birds none are more interesting in their habits than the species of Heterorhynchus ” (Perkins 1903: 427). These admiring words, written a hundred years ago by the person most familiar with ‘Akiapölä‘au and Nukupu‘u (then known under genus Heterorhynchus), still ring true today. Yet despite the charm and novelty of these birds, we know surprisingly little about them. Nineteenth-century naturalists described their distributions and habits at a time when both species were much more numerous. Since then the Nukupu‘u has disappeared. Occasional reports from the twentieth century vary in reliability, some being misidentifications, and none has shed new light on this mysterious species (Pratt and Pyle 2000). Consequently, for information on Nukupu‘u we must depend on eyewitness reports prior to 1900 and on about 100 study skins distributed among museums worldwide. In this account, the three Nukupu‘u taxa—Kaua‘i Nukupu‘u (Hemignathus l. hanapepe), O‘ahu Nukupu‘u (H. l. lucidus), and Maui Nukupu‘u (H. l. affinis)—are treated separately to document comparisions among them (see Systematics: geographic variation; subspecies, below). Recent information on ‘Akiapölä‘au is cited from the little existing published research and gleaned from data contributed by numerous field biologists. It includes a three-year, weekend study of a now-extinct, color-banded population at Kanakaleonui on Mauna Kea (1989–1992; TKP and P. Chang). This fascinating species has yet to be the focus of intensive field research. bna.birds.cornell.edu/ |

|

|

|

Post by Peter on Jul 13, 2014 11:08:48 GMT

According to H. Douglas Pratt ('The Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Drepanidinae') all three Nukupu'u's should be regarded full species. The two species from Maui and O'ahu are closer related to the Akiapola'au thean to the Kaua'i Nukupu'u. Thread been renamed Still officially regarded as subspecies by: - BirdLife International (2013). The BirdLife checklist of the birds of the world, with conservation status and taxonomic sources. Version 6. Downloaded from www.birdlife.org/datazone/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/BirdLife_Checklist_Version_6.zip [.xls zipped 1 MB].

- Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, B.L. Sullivan, C. L. Wood, and D. Roberson. (2013). The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: Version 6.8. Downloaded from www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/.

- Gill, F. & D. Donsker (Eds). (2014). IOC World Bird List (v 4.2). doi : 10.14344/IOC.ML.4.2.

- Hume J.P. & Walters M. (2012). Extinct birds. London: T & AD Poyser, 544 pp. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- Lepage, D. & Warnier, J. (2014). The Peters' Check-list of the Birds of the World (1931-1987) Database. Accessed on 18/06/2014 from Avibase, the World Database: avibase.bsc-eoc.org/peterschecklist.jsp.

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Mar 28, 2015 8:52:52 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Sebbe on Jul 19, 2015 15:36:17 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Sebbe on Jul 19, 2015 15:42:45 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by surroundx on Sept 19, 2016 8:34:33 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Sebbe on Oct 16, 2016 14:08:35 GMT

|

|