|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:39:58 GMT

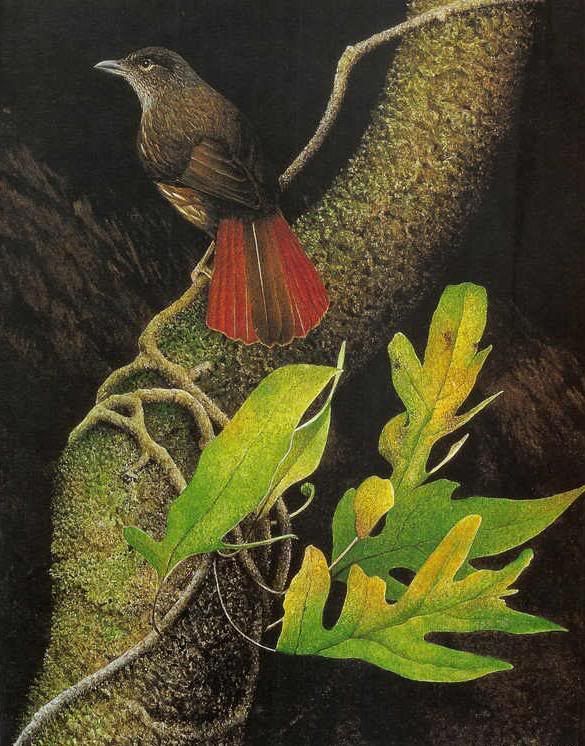

Piopio, the New Zealand Thrush (Turnagra capensis) is unfortunately now extinct. This omnivorous, medium sized perching bird had a plumage of olive brown, rufous, yellow and yellowish-white. Its bill and feet were dark brown. It was about the same size as the New Zealand Tui (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae). The European name is misleading since its resemblance to the Song Thrush (Turdus philomelos) seems coincidental. Piopio is thought to be related to the Bowerbirds of Australia. The North Island sub-species (pictured) was described by early settlers as "unquestionably the best of our native songsters". At the time of European settlement it was widespread in forest throught the country. It was tame and is recorded as taking food scraps at bush camp sites. By 1888 it was said to be one of New Zealand's rarest species and by 1905 was quoted almost extinct. The last recorded North Island Piopio was shot at Ohura in 1902. Despite extensive searches over recent years, there have been no positive sightings. The main reasons for the decline of this magnificent bird seem to be the destruction of its forest habitat, and the introduction of mammalian predators.  www.foek.hu/dodo/madar/tuca.htm www.foek.hu/dodo/madar/tuca.htm |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:41:11 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:42:16 GMT

Turnagra capensis capensis (South Island) and Turnagra capensis tanagra (North Island). a worth while read is this Were bowerbirds part of the New Zealand fauna? www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/93/9/3898.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:48:10 GMT

Piopio Confusing names Neither the English nor the scientific name of the Piopio Turnagra capensis ( Sparrman, 1787) is appropriate. The bird is often referred to as the New Zealand Thrush. It bears, however, no relationship whatsoever to the thrushes. This name seems to have been given by an early, homesick naturalist. Or maybe less romantically, by someone who tried to place all new birds into known groups. Several other New Zealand bird names inappropriately refer to European species, such as the New Zealand wrens. The scientific name capensis, meaning 'from the Cape', is equally confusing. The Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman, by invitation of Johann and Georg Forster, had sailed with Captain Cook on his second voyage to New Zealand. When Sparrman returned to his home in the Cape Province, South Africa, he did not remember all localities where the birds in his collection had been shot. Apparently he was under the impression that the Piopio came from somewhere in South Africa. www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:48:26 GMT

Two subspecies At the time of its discovery, the species was quite common on South Island and in the southern parts of North Island, where it lived both on the coastal plains and in the mountains. The second director of the National Museum of Natural History, Hermann Schlegel, recognized that the birds from North Island differed from those of South Island, particularly in the breast, which is more heavily streaked in the North Island birds. In 1866, he described this Piopio as a separate species, Otagan tanagra. Nowadays the North and South Island forms are considered two different subspecies of the Piopio. The Piopio was a tame and confiding bird, which did not seem to be disturbed by human presence. However, as with so many endemic New Zealand birds, the introduction of dogs and cats led to its disappearance. The North Island race became extinct about 20 years after it had been described. Around the turn of the century the South Island Piopio too, had practically vanished, though it managed to linger on until at least 1947. It has not been seen since. www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 15:49:23 GMT

The museum collection The National Museum of Natural History possesses three specimens of the Northern subspecies, among which the skin used in Schlegel's description and six of the South Island Piopio. www.naturalis.nl/300pearls/ |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:05:56 GMT

Pachycephalidae (Whistlers) Piopio or New Zealand Thrush Turnagra capensis capensis (Sparrman, 1787)  RMNH 110.040: September 1873.  RMNH 110.041: male. Big bay, Southern Island, New Zealand. Collector: H. Suter, 16 October 1905.  RMNH 110.056: New Zealand. Bought from: Frank, 1876.  RMNH 110.057: adult, female. Southern Island, New Zealand. Aqcuired: 1846.  RMNH 110.058: juvenile, female. Southern Island, New Zealand. Aqcuired: 1846.  RMNH 110.059: adult, male. Southern Island, New Zealand. Aqcuired: 1846. Inappropriate name Neither the English nor the scientific name of the Piopio is appropriate. The bird is often referred to as the New Zealand Thrush. However it bears no relationship whatsoever with the thrushes. This name seems to have been given by an early, homesick naturalist or, somewhat less romantic, by someone who tried to place all new birds in known groups. Other New Zealand birdnames too often injustly refer to European species, such as the New Zealand Bush Wren Xenicus longipes. The scientific name capensis, meaning “from the Cape”, is equally confusing. The Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman, on the invitation of Johann and Georg Forster, sailed with Captain Cook on his second voyage to New Zealand. When Sparrman returned to his home in the Cape Province, South Africa, he did not remember all localities where the birds in his collection had been shot. Apparently he was under the impression that the Piopio came from somewhere in South Africa. At the time of its discovery, the species was quite common on South Island and in the southern parts of North Island, where it lived both on the coastal plains and in the mountains. The second director of the Leiden Museum, Hermann Schlegel, recognized that the birds from North Island differed from those of South Island, particularly in the breast, which is more heavily streaked in the North Island birds. In 1865 he described this Piopio as a separate species. Nowadays the North and South Island forms are generally considered two different subspecies of the Piopio. The Piopio was a tame and confiding bird, which did not seem to be disturbed by human presence. However, as with so many endemic New Zealand birds, the introduction of dogs and cats led to its disappearance. The North Island race became extinct about 35 years after it had been described, although there were unconfirmed reports until 1955. Around the turn of the century the South Island Piopio too had practically vanished, but it seemed to have managed to linger on until 1963. It has not been seen since. Museum specimens The Leiden Museum possesses three specimens of the northern subspecies (among which the holotype, the skin used in Schlegel's description) and six of the South Island Piopio. ip30.eti.uva.nl/naturalis/detail?lang=uk&id=35 |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:06:44 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:08:20 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:09:26 GMT

New Zealand Extinct Birds Brian Gill and Paul Martinson |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:10:34 GMT

Bird on right is South Island and bird on left is North Island. gap in nature |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:15:15 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:24:08 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:28:43 GMT

Piopio, the New Zealand Thrush  Turnagra capensis by Walter Lawry Buller There is a peculiar charm about the New Zealand forest in the early morning; for shortly after daylight a number of birds of various kinds join their voices in a wild jubilee of song, which, generally speaking is of very short duration. This was the morning concert to which Captain Cook referred in such terms of enthusiasm; and the woods of Queen Charlotte's Sound, where his ship lay at anchor, are no exception to the general rule. In illustration of this, I take the following from an entry in one of my notebooks: 'Tuesday, 5 a.m. - At this moment the wooded valley of the Mangaone, in which we have been camped for the night, is ringing with delightful music. It is somewhat difficult to distinguish the performers amidst the general chorus of voices. The silvery notes of the Bellbird, the bolder notes of the Tui, the loud continuous strain of the native Robin, the joyous chirping of a flock of Whiteheads, and the whistling cry of the Piopio - all these voices of the forest are blended in wild harmony. And the music is occasionally varied by the harsh scream of a Kaka passing overhead, or the noisy chattering of Parakeets on a neighbouring tree, and at regular intervals the far off cry of the Long-tailed Cuckoo and the whistling call of its bronze-winged congener; while on every hand may be heard the soft trilling notes of Myiomoira toitoi.' For more than an hour after this concert had ceased, and the sylvan choristers had dispersed in search of their daily food, one species continued to enliven the valley with his musical notes. This bird was the Piopio, or New Zealand Thrush, the subject of the present article, and unquestionably the best of our native songsters. His song consists of five distinct bars, each of which is repeated six or seven times in succession; but he often stops abruptly in his overture to introduce a variety of other notes, one of which is a peculiar rattling sound, accompanied by the spreading of the tail, and apparently expressive of ecstasy. Some of the notes are scarcely distinguishable from those of the Yellowhead; and I am inclined to think the bird is endowed with mocking powers. The ordinary note, however, of the Piopio, whence it derives its name, is a short, sharp whistling cry, quickly repeated. It was when I obtained a caged Piopio that I first became acquainted with its superior vocal powers. In 1866 I purchased one for a guinea from a settler in Wellington, in whose possession it had been for a whole year. Although an adult bird when taken, it appeared to have become perfectly reconciled to confinement; but on being placed in a new cage it made strenuous assaults on the wire bars, and persevered until the feathers surrounding its beak were rubbed off and a raw wound exposed. It then desisted for several days; but when the abraded part had fairly healed, it renewed the attempt, and with such determined effort that the fore part of the head was completely disfigured, and the life of the bird endangered. On being removed, however, to a spacious compartment of the aviary, it immediately became reconciled to its condition, made no efforts to escape, and for a period of fifteen months (when it came to an untimely end) it continued to exhibit the contentment and sprightliness of a bird in a state of nature. I observed that this bird was always most lively during or immediately preceding a shower of rain. He often astonished me with the power and variety of his notes. Commencing sometimes with the loud strains of the Thrush, he would suddenly change his song to a low flute note of exquisite sweetness; and then abruptly stopping, would give vent to a loud rasping cry, as if mimicking a pair of Australian magpies confined in the same aviary. During the early morning he emitted at intervals a short flute note, and when alarmed or startled uttered a sharp repeated whistle. This caged bird was generally fed on dry pulse or grain; but he also evinced a great liking for cooked potato and raw meat of all kinds; in fact he appeared to be omnivorous, readily devouring earthworms, insects of all kinds, fruits, berries, green herbs, &c. He was supplied daily with a dish of fresh water, and was accustomed to bathe in it with evident delight. At one time he occupied the same division of the aviary with a pair of Australian Ring-Doves which had commenced to breed. The Doves were allowed to bring up their first brood in peace; but when the hen bird began to build a second time, she was closely watched by the Piopio, and immediately the first egg was deposited he darted upon the nest and devoured it. The innocent little Ring-Dove continued to lay on in spite of repeated robbery, and had at length to be placed beyond the reach of her persecutor. During the day the Piopio was unceasingly active and lively; at night he slept on a perch, resting one leg, and with the plumage puffed out into the form of a perfectly round ball, the circular outline broken only by the projecting extremities of the wings and tail. Every sound seem to attract his notice, and he betrayed an inquisitiveness of disposition which in the end proved fatal; for having inserted his prying head through an open chink in the partition, it was seized and torn off by a vicious Sparrow-Hawk in the adjoining compartment of the aviary. In the wild state this species subsists chiefly on insects, worms and berries. I have shot it on the ground in the act of grubbing with its bill among the dry leaves and other forest debris. Its flight is short and rapid. It haunts the undergrowth of the forest, darting from tree to tree, and occasionally descending to the ground, but rarely performing any long passage on the wing. It is very nimble in its movements; and when attempting on one occasion to catch one of these birds with an almost invisible horsehair noose, it repeatedly darted right through the snare, and defeated every effort to entrap it. Sir James Hector informs me that, during his exploration of the West Coast in the years 1862-63, he found it very abundant, and on one occasion counted no less than forty in the immediate vicinity of his camp. They were very tame, sometimes hopping up to the very door of his tent to pick up crumbs; and he noticed that the camp dogs were making sad havoc among them. He is of the opinion that within a few years this species would also be numbered among the extinct ones. Mr Potts, who studied this bird pretty closely in Wetland, states that the nest is generally found among the thick foliage of the Tutu, Coriara ruscifolia, but sometimes in Karamu or Manuka, that it is sometimes finished off with soft tree-fern down as lining, and that it usually contains two eggs; and he is of the opinion that the bird breeds twice in the season.  www.nzbirds.com/Piopio.html www.nzbirds.com/Piopio.html

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Jan 2, 2007 16:35:43 GMT

Turnagra capensis Common Name/s SOUTH ISLAND PIOPIO (E) Species Authority (Sparrman, 1787) Taxonomic Notes The taxon was traditionally considered conspecific with the North Island form, but recent work has shown it to be distinct. Red List Category & Criteria EX ver 3.1 (2001) Year Assessed 2004 Assessor/s BirdLife International Evaluator/s Stattersfield, A. (BirdLife International Red List Authority) & Brooks, T. (Conservation International) Justification South Island Piopio Turnagra capensis, according to Buller, was common until 1863 in forest undergrowth on the South Island, New Zealand, from where it is known from numerous specimens. However, the species declined very rapidly in the 1880s, probably mainly due to predation by introduced rats, and the last sight record was from 1963. Taxonomy The taxon was traditionally considered conspecific with the North Island form, but recent work has shown it to be distinct. History 1988 - Extinct (BirdLife International 2004) 1994 - Extinct (Groombridge 1994) 2000 - Extinct (BirdLife International 2000) Range Turnagra capensis, according to Buller, was common until 1863 in forest undergrowth on the South Island, New Zealand, from where it is known from numerous specimens1. However, the species declined very rapidly in the 1880s, probably mainly due to predation by introduced rats1, and the last sight record was from 19633. www.iucnredlist.org/search/details.php/22552/all |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Apr 10, 2008 3:39:12 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by Melanie on Jul 12, 2008 21:42:54 GMT

Turnagra Crassirostris, (South-Island Thrush.)

Thick-billed Thrush, Lath. Gen. Syn. ii. pt. 1, p. 34, pl. xxxvii. (1783).

Tanagra capensis, Sparrm. Mus. Carls. pl. 45 (1787).

Turdus crassirostris, Gm. Syst. Nat. i. p. 815 (1788, ex Lath.).

Lanius crassirostris, Cu, v. Regn. Anim. p. 338 (1817).

Campephaga ferruginea, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. d'Hist. Nat. x. p. 48 (1817).

Tanagra macularia, Quoy et Gaim. Voy. de 1'Astr. i. p. 186, pl. vii. fig. 1 (1830).

Keropia crassirostris, Gray, List of Gen. of B. p. 28 (1840).

Turnagra crassirostris, id. op. cit. p. 38 (1841).

Loxia turdus, Forst. Descr. Anim. p. 85 (1844).

Otagon turdus, Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av. i. p. 374 (1850).

Ceropia crassirostris, Sundev. Krit. Framst. Mus. Carls. p. 9 (1857).

Turnaqra turdus, Gray, Hand-1. of B. i. p. 284 (1869).

Ad. supra olivaceo-brunneus, pileo vix cinerascente irregulariter fulvo striato: tectricibus alarum dorso

concoloribus, rufo terminatis, fasciam duplicem alarem exhibentibus: remigibus brunneis, extus dorsi

colore marginatis, primariis ad basin rufo lavatis: supracaudalibus rufo tinctis, imis omnino rufs: cauda læte

rufa, rectricibus duabus mediis et reliquarum apicibus olivaceo-brunneis: loris cum regione oculari

genisque brunneis pallide rufo maculatis: regione parotica pileo concolore, anguste fulvo striata: subtus

olivascens, gutture toto rufescente lavato, plumis medialiter fulvescentibus: pectoris plumis medialiter

albidis, utrinque olivaceo marginatis, quasi striatis: pectore superiore vix rufescente lavato: hypochondriis

magis olivascentibus; abdomine imo et subcaudalibus flavo lavatis: subalaribus rufis: rostro pedibusque

saturate brunneis: iride flava.

Adult. General plumage olive-brown, darker on the upper parts; forehead, lores, throat, and sides of

neck largely marked with rufous; breast, abdomen, and under tail-coverts covered with broad

longitudinal spots of yellowish white, narrower towards the sides of the body; on the abdomen and under

tail-coverts less of the olive-brown, with a strong tinge of yellow; wing-feathers dark olive-brown, dusky

on their inner webs; the superior and lesser wing-coverts largely tipped with rufous, forming two broad

transverse bars; lining of wings pale rufous; tail, for the most part, with the upper coverts bright rufous,

the two middle feathers and the apical margins of the rest olive-brown, only slightly tinged with rufous.

Irides yellow; bill and feet dark brown. Total length 11 inches; wing, from flexure, 5; tail 5; bill, along the

ridge ·7, along the edge of lower mandible ·8; tarsus 1·25; middle toe and claw 1·15; hind toe and claw

1.

Young. May be distinguished from the adult by the larger amount of rufous colouring on the forehead,

sides of the head, throat, and upper wing-coverts.

Obs. In some specimens the bend of the wing and the exterior edges of the outer primaries are also

marked with rufous. The colour of the bill likewise varies, in different examples, from a light brown to

dusky black.

Thisfine species is confined to the South Island. Formerly it was excessively abundant in all the elevated

wooded country; but of late years it has become comparatively scarce, while in some districts it has

disappeared altogether. This result is attributable, in a great measure, to the ravages of cats and dogs, to

which this species, from its ground-feeding habits, falls an easy prey.

Sir James Hector informs me that, during his exploration of the West Coast in the years 1862-63, he

found it very abundant, and on one occasion counted no less than forty in the immediate vicinity of his

camp. They were very tame, sometimes hopping up to the very door of his tent to pick up crumbs; and

he noticed that the camp-dogs were making sad havoc among them. He is of opinion that in a few years

this species also will be numbered among the extinct ones.

Mr. Buchanan, of the Geological Survey, assures me that in the woods in the neighbourhood of Dunedin, where it was formerly very common, it has been quite exterminated by the wild cats. It may be here

observed that there is no indigenous cat in our country; but ill-fed or ill-used members of the race, in the

struggle for existence, frequently quit the settlers’ houses and betake themselves to the woods, where

they, in course of time, produce a purely wild breed. To this cause is partly owing the almost entire

extermination of the Quail and other ground species.

It is worthy of remark that Mr. Burton obtained a specimen on Stephens Island on the south side of

Cook's Strait.

The habits of this bird differ in no respect, so far as I am aware, from those of its congener in the North

Island. The following incident is illustrative of its predaceous nature:—My brother, Mr. Fletcher Buller,

while residing in Canterbury, obtained a live one from the woods, and placed it in a cage with a pair of

tame Parrakeets ( Platycercus novoe-zealandioe). On the following morning he found, to his dismay,

that the newly introduced bird had slain both of his fellow prisoners, and was actually engaged in eating

off the head of one of them|

There is a nest of this bird in the Canterbury Museum, obtained from the River Waio, County of

Westland. It is a round nest, somewhat loosely constructed, composed of small, dry twigs, shreds of

bark, fragments of moss, &c., with a rather large cup-shaped cavity, lined with dry grasses and other

fibres. To all appearance it is carelessly, but nevertheless firmly, fixed in the forked twigs of a small

upright branch. In the same collection there is another nest from Lake Mapourika, which is formed of soft

green moss on a tapering foundation of small twigs, completely filling the crutch of a manuka fork and

being fully a foot in depth. Another, formed externally of dry twigs, is of more irregular shape, but is

likewise built in a forked branch as a means of support. The circular cup is neatly lined with dry bents.

Mr. Potts, who studied this bird pretty closely in Westland, states that the nest is generally found among

the thick foliage of the tutu ( Coriaria ruscifolia), but sometimes in karamu or manuka, that it is

sometimes finished off with soft tree-fern down as a lining, and that it usually contains two eggs; and he is

of opinion that the bird breeds twice in the season. The Museum collection contains four specimens of the

egg, which exhibit considerable difference in form. Two of them—probably from one nest—are very

ovoido-conical; one of these measures 1·3 inch by 1·05 inch, and is pure white, marked at irregular

distances over the entire surface with specks and roundish spots of blackish brown. The other is slightly

narrower in form, the white is not so pure, and the markings are less diffuse, being collected into

reddish-brown blotches towards the larger end. The other two eggs (apparently also from one nest) are

of a long ovoido-elliptical form, and of equal size; the one I tested measuring 1·6 inch in length by ·95 of

an inch in its widest part. The shell is pure white, with widely-scattered irregular spots of blackish brown,

less numerous and of smaller size in one than in the other. Both eggs have a rather glossy surface.

Source: A History of the Birds of New Zealand.

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Oct 20, 2008 9:07:22 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 4, 2008 17:44:14 GMT

Thick-billed Thrush( Piopio, the New Zealand Thrush) Plate LXXX: Hand coloured engraving from A General Synopsis of Birds published London, 1795. Printed on hand woven, fleur de lis watermarked, laid paper. It carries an 1821 watermark. Plate size: 8 x 10 1/2 inches (20 x 26cm) approximately. Condition: very good, there is a 1.5cm tear in top margin, see larger photograph. www.newzealandantiqueprints.co.nz/gallery/birds/latham.html |

|

|

|

Post by another specialist on Dec 27, 2008 12:27:32 GMT

|

|